How to eavesdrop on kelp

Listening to underwater forests could help monitor ocean health

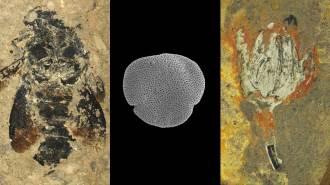

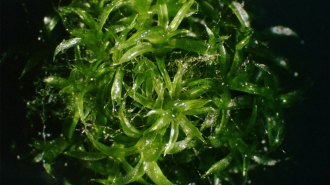

HEAR THIS Projected sound reverberating through a kelp bed can tell scientists about the ecosystem, a new analysis shows. The approach may lead to a cheap, efficient way to monitor the health of kelp forests.

Spiderment/iStockphoto

- More than 2 years ago

BOSTON — If kelp growing in an underwater forest makes a sound, such noises could be used to keep tabs on ocean health.

Listening to how projected sound reverberates through kelp beds allows scientists to eavesdrop on environmental factors such as water temperature and photosynthetic activity, bioacoustician Jean-Pierre Hermand reported June 28 at a meeting of the Acoustical Society of America.

Kelp beds and forests, valuable ecosystems that house all sorts of marine life, may help buffer the effects of warmer and increasingly acidic waters (SN Online: 12/14/16). But such communities are also threatened by invasive species and aren’t immune to the effects of climate change, making monitoring kelp crucial, said Hermand, of the Université libre de Bruxelles in Belgium.

Hermand and colleagues set up microphones in Canoe Bay off Tasmania in Australia. There, Ecklonia radiata, a dominant kelp species in Australia’s reefs, grows thickly. For two weeks, the researchers deployed an underwater device that emitted a chirp every second. The underwater microphones — two in the kelp canopy and two above the canopy — recorded the chirps bouncing off everything in the environment from oxygen bubbles from photosynthesis burbling up from the kelp to the kelp itself to the water’s surface.

More than 20 fixed sensors in the water column, within and above the kelp canopy, collected all kinds of environmental data that might relate to ecosystem health. That data included dissolved oxygen in the water, pH, water temperature, salinity, photosynthetic activity and turbidity. Wind speed, which generates audible bubbles in the surface waters, was also logged.

Then the researchers examined the acoustic data, measured in decibels of energy, alongside the measured environmental variables. Mathematical analyses revealed consistent connections between the recorded sound and the environmental factors, suggesting that eavesdropping could be a good way to monitor the kelp beds, Hermand said.

While the research is preliminary, it could lead to a relatively inexpensive and efficient method for assessing the well-being of kelp beds and other marine ecosystems, says acoustics expert Preston Wilson of the University of Texas at Austin. Current methods, such as using satellite imagery, are expensive and don’t provide much detail, while hand-conducted surveys are time-consuming and labor-intensive, Wilson says, who does related research in kelp and seagrass communities.

Years of research went into learning how to eavesdrop on a sea forest. For example, to tease out what various sound signals might mean, the researchers had to figure out how kelp tissues respond to sound (turns out that it’s highly dependent on alginate content, a gummy cell wall component of kelp). And there’s much work ahead, Hermand said. Rather than relying on a device that chirps and then capturing that sound as it bounces around, the ultimate goal is to be able to learn about the kelp environment from listening alone. “Ambient noise — that’s my dream,” Hermand said.