A bounty of potential gravitational wave events hints at exciting possibilities

Most are probably false alarms, but some could be spacetime ripples that are extra hard to spot

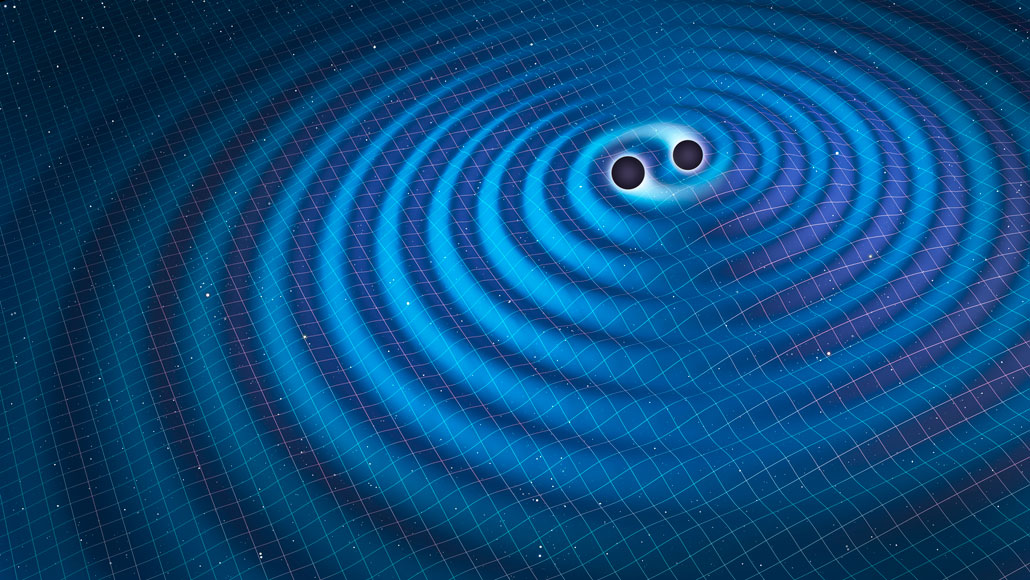

One way that gravitational waves (shown in this illustration) are stirred up is when two black holes spiral around one another and collide.

MARK GARLICK/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY