Genetically modified mosquitoes have been OK’d for a first U.S. test flight

As dengue cases rise in the Florida Keys, a much-debated public health tool gets a nod for 2021

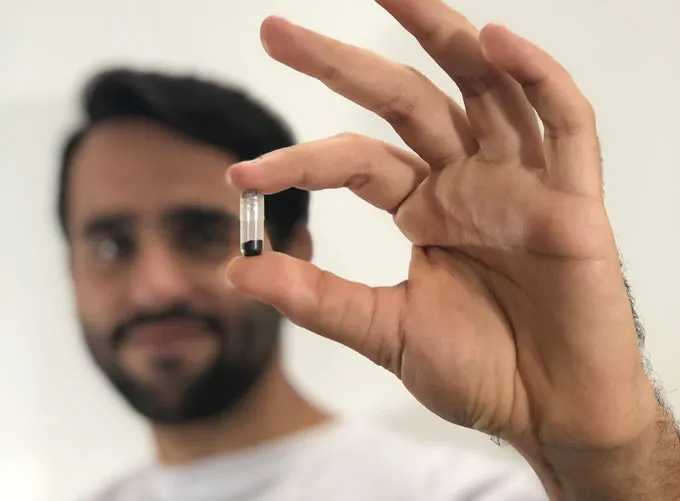

The first U.S. tests of any free-flying genetically modified mosquito are now OK’d for 2021 to fight the dengue-spreading Aedes aegypti (shown).

Oxitec

After a decade of fits and starts, officials in the Florida Keys have voted to allow the first test in the United States of free-flying, genetically modified mosquitoes as a way to fight the pests and the diseases they spread.

The decision came after about two hours of contentious testimony in a virtual public hearing on August 18. Many speakers railed against uncertainties in releasing genetically engineered organisms. In the end, though, worries about mosquito-borne diseases proved more compelling. On the day of the vote, dengue fever cases in Monroe County, where the Keys are located, totaled 47 so far in 2020, the first surge in almost a decade.

The same mosquitoes known for yellow fever (Aedes aegypti) also spread dengue as well as Zika and Chikungunya (SN: 6/2/15). The species is especially hard to control among about 45 kinds of mosquitoes that whine around the Keys. Even the powerhouse Florida Keys Mosquito Control District with six aircraft for spraying — Miami has zero — kills only an estimated 30 to 50 percent of the local yellow fever mosquito population with its best pesticide treatments, says district board chairman Phil Goodman.

“We can’t rely on chemistry to spray our way out of this,” Goodman, a chemist himself, said as the commissioners conferred after the public’s comments. Then 4–1, the commissioners voted to go forward with a test of genetically modified males as pest control devices.

Sometime after January 1, 2021, Florida workers will set out boxes of eggs of specially bred male yellow fever mosquitoes (a recent version called OX5034) in a stretch of Monroe County still to be chosen. The eggs, shipped from the biotech company Oxitec based in Abingdon, England, will grow into normal-looking males. Like other male mosquitoes, they drink flower nectar, not blood.

Then planners hope that during tests, these Oxitec foreigners will charm female mosquitoes into mating. A bit of saboteur genetics from the males will kill any female offspring resulting from the mating, and over time that should shrink the swarms. Sons that inherit their dad’s no-daughter genes will go on to shrink the next generation even further.

By now, Oxitec has supplied some billion saboteur male mosquitoes for release elsewhere around the world, especially in Brazil, where Zika can flare up and dengue is common (SN: 7/15/16). The notion of releasing sterile males of a pest to romance the population down to some scattered lonely hearts is at least 80 years old (SN: 6/29/12). For decades, that meant sterilizing males by exposing them to radiation and then releasing them into the wild. But mosquitoes were too delicate for the radiation techniques of the time. When scientists figured out an efficient way to tweak a fruit fly’s natural DNA, reported in 1982, hopes rose for genetically sterilizing male pest insects.

In Oxitec’s method, some of the mosquito genes of the breeding stock not involved in the daughter-killing mechanism can spread a bit into any wild populations of the species, at least for a while. Yet researchers have argued that Ae. aegypti mosquitoes probably hitchhiked on ships into the Americas, so preserving their wild genetics in the United States would just mean coddling an invasive species. Also, introducing some gene that would make the U.S. wildlings more of a nuisance than they already are seems unlikely, says public health entomologist Kevin Gorman from Oxitec.

In spite of years of drama over the Keys’ consideration of releasing GM mosquitoes (SN: 5/8/17), Florida’s batch will not be the first GM insects to fly free in the United States. (And if it weren’t for COVID-19, they might not be the only mosquito pioneers; the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency simultaneously approved an experimental release in Houston’s Harris County, now on hold during the pandemic.) The first GM insects released in the United States, also from Oxitec, were early versions of pink bollworm moths for an eradication program to wipe out this cotton pest in the U.S Southwest. That genetic tweak merely supplied a marker that would identify irradiated insects but didn’t change any fertility genes.

The first GM insects with fertility tweaks (Oxitec again) were diamondback moths (SN: 7/14/17). “We would love to have been the second,” says entomologist Tony Shelton of Cornell University. Instead the first-of-its kind project sparked 673 individual comments, 78 percent of them not happy, when regulators posted the application to release the moths in 2017 in a New York field.

The new application to test GM mosquitoes in Florida, however, got 5,656 comments, plus a petition against the project that drew more than 25,000 signatures. Even though people probably detest mosquitoes more than moth larvae that can damage broccoli, the fact that the Florida Keys project involves genetic modification still stirs passion.

As far as specific concerns go, one common one involves antibiotics, says Oxitec’s Gorman. To keep females in the breeding stock alive, the company adds the antibiotic tetracycline to the water where the larvae dangle rump-up before transitioning to aerial adulthood. That suppresses the killing mechanism, which involves a protein that’s blocked by tetracycline. When people put eggs in the wild, there’s no antibiotic, so daughters die. The egg parents’ history with antibiotics has raised concerns that egg releases might encourage the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Gorman contends that that’s not likely. The EPA has required testing sites at least 500 meters away from sewage plants (where antibiotics show up in waste and in theory might keep some daughters alive) and citrus orchards (which can get treated with antibiotics for their own diseases). Also, the latest version of these mosquitoes is shipped from the United Kingdom as cleaned male eggs. Their moms laid the eggs as adults living in air instead of in the youngsters’ tetracycline-tinged soup.

Some of the more general objections to the project may have more to do with suspicions of government and for-profit businesses than with mosquito biology. Some unease, too, may come just from basic human reactions to risk and control, says public health entomologist Natasha Agramonte, who has no connection with Oxitec but has been working with mosquitoes at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Car crashes injure several million Americans a year, but driving lets people feel they’re in control. Watching abundant mosquitoes being released, though? Not so much.