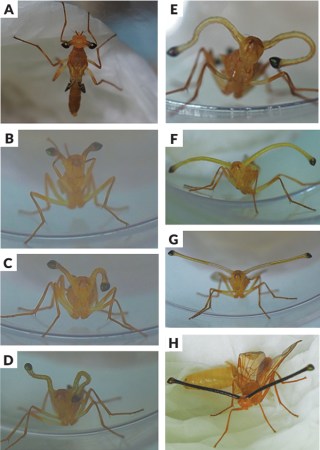

Certain young fruit flies’ eyes literally pop out of their head

The first “biological portrait” of Pelmatops flies reveals how their eyes really stand out

With eyeballs sticking out at the end of extravagant stalks on its head, a long skinny male fruit fly (Pelmatops tangliangi) prowls shrubbery after the swift and weird extension of its eyes.

Yong Wang