Fossil whale skull hints at echolocation’s origins

Underwater sonar may have developed 34 million years ago

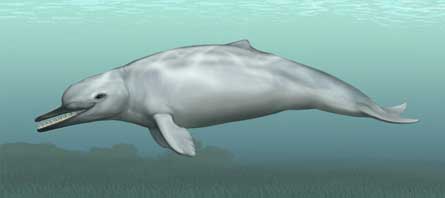

PING ME The skull of the 28-million-year-old Cotylocara macei suggests that this early toothed whale used echolocation.

James Carew and Mitchell Colgan

- More than 2 years ago

The skull of a newly identified species of extinct toothed whale may help scientists piece together when echolocation evolved underwater.

Recovered from a drainage ditch in South Carolina, the 28-million-year-old fossil has a deep pit in the top of its head that divides the right and left sides of the skull. “It’s a highly unusual feature,” says Jonathan Geisler, an anatomist at the New York Institute of Technology in Old Westbury, adding that no other known whale, dolphin or porpoise has such a pit. “It’s really bizarre.”

Geisler and his colleagues named the species Cotylocara macei (the genus name means “cavity head” in Greek). The pit and other skull features suggest that the ancient toothed whale used echolocation to send calls out into the water. The age of the skull and the animal’s relationship to other extinct whales suggest that the basic anatomy for echolocation developed shortly after toothed whales split from filter-feeding whales 35 million years ago, Geisler and his colleagues argue March 12 in Nature.

The skull of C. macei, dated to 28 million years ago based on the age of layer of soil it was found in, is 55 centimeters long and 27 centimeters wide. That makes the head comparable in size to a bottlenose dolphin’s but with a slightly longer snout. The whale had features — thickening of the bone bordering the nasal opening, cavities in the back of the snout and a broad upper jaw — typically found in younger toothed whale species that echolocate, including modern animals. The similarities imply that C. macei probably used these traits to make sound, says Philip Gingerich, a paleontologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “It would be difficult to interpret these observations any other way.”

Unfortunately, not many of C. macei’s ear bones were recovered, says John Gatesy, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Riverside. “The structures preserved in the specimen examined here mostly have to do with sound generation and not hearing the echoed sounds that come back to the whale.”

Geisler hopes to analyze other species closely related to C. macei to provide a more complete view of the evolution of echolocation. “The layers of sediment around the Charleston area are very rich in whale fossils and there are a lot more we need to describe,” he adds.

Because of its excellent preservation, C. macei’s skull provides conclusive evidence that rudimentary echolocation emerged at least 28 million years ago. Analyzing when certain features needed for echolocation may have evolved in species that lived before and after C. macei, the team estimates that echolocation may date back as far as 30 million to 34 million years ago. This period is also when C. macei’s ancestors, part of a now-extinct lineage, split from the ancestors of living toothed whales, dolphins and porpoises.

Geisler adds that whale fossils could even provide information about the anatomical changes that may have allowed echolocation to evolve in other species, such as bats. That’s because some bats that release sonar through their noses have a downturned snout similar to toothed whales’. “The fossil record doesn’t have all the answers but it’s starting to show how complex features such as echolocation evolved bit by bit over time,” he says.