Fossil shows that ancient reptile gave live birth

Archosauromorph ditched eggs, unlike bird, crocodile cousins

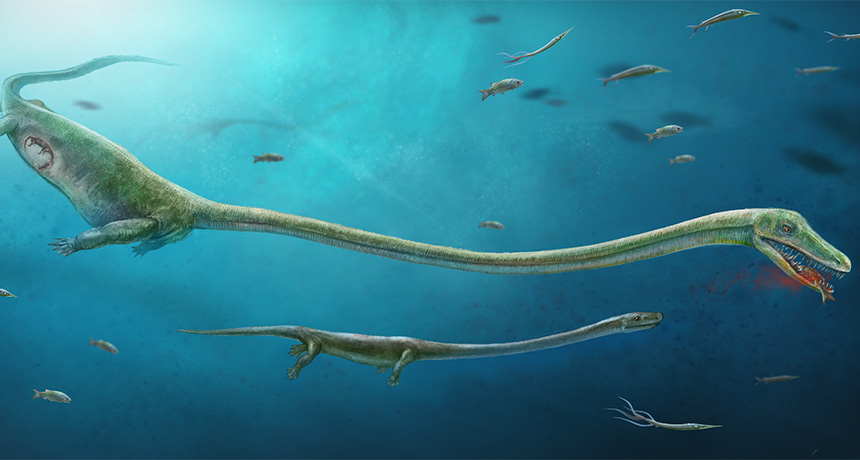

PREHISTORIC PREGNANCY With a long-necked body not suited to walking, an ancient marine reptile Dinocephalosaurus (illustrated) may have evolved to give live birth in the ocean rather than lay eggs on land, a new study suggests.

Dinghua Yang, J. Liu

- More than 2 years ago

A prehistoric marine reptile may have given birth to its young alive.

A fossil from South China may be the first evidence of live birth in the animal group Archosauromorpha, scientists report February 14 in Nature Communications. Today Archosauromorpha is represented by birds and crocodiles — which both lay eggs.

Whether this fossil really is the first evidence of live birth in Archosauromorpha depends on how another group of semiaquatic animals is classified, says Michael Caldwell, a vertebrate paleontologist with the University of Alberta in Canada. Placement of Choristodera, a now-extinct group that included a freshwater reptile that gave live birth, remains murky, with some researchers putting them with Archosauromorpha and others with a group that includes snakes and lizards.

“Our discovery is the first of live birth in reptiles with undoubted archosauromorph affinity,” says Jun Liu, a paleontologist at Hefei University of Technology in China.

Researchers have speculated that the biology of archosauromorphs prevented their reproductive traits from evolving, says study coauthor Chris Organ, an evolutionary biologist with Montana State University in Bozeman. This find may disprove that view.

“Ancestrally, the science suggests that live birth is not absolutely prohibited,” Organ says. Even though birds and crocodiles haven’t yet evolved to give live birth, this discovery suggests that it’s possible.

Story continues below image

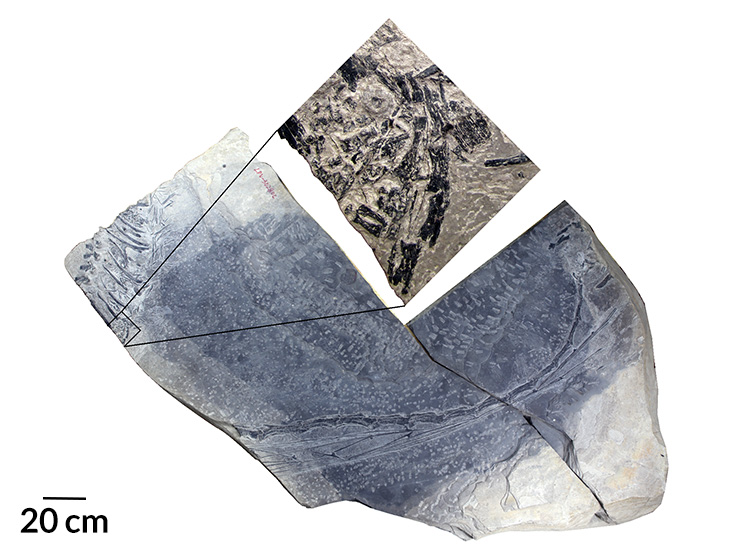

Researchers determined that the fossil of the long-necked marine reptile, known as Dinocephalosaurus, was pregnant because of the position of the smaller reptile enclosed within it. The embryo is curled in the fetal position and its head points forward. The marine reptile swallowed fish headfirst, so it’s not likely that the smaller animal is an undigested meal. There were also no traces of eggshell in the fossil.

“The fossil embryo is pretty partial and fragmentary,” Caldwell says. But “it looks pretty convincing…. It’s in a good position to be an embryo, and position is everything.”

Live birth for Dinocephalosaurus makes sense because its giraffelike neck, longer than the rest of its body, would have made coming ashore to lay eggs difficult, Liu says.

The discovery of live birth in the ocean-dwelling Dinocephalosaurus supports a theory that Organ put forth in Nature in 2009.

If an egg-laying land animal evolved to live in the ocean, it may have developed adaptations that made it difficult to return to land — like the long neck of Dinocephalosaurus. Organ and his colleagues predicted that these marine animals are most likely to also evolve to give live birth.

“It’s really this great Darwinian thing,” Organ says.