This small shark, called a rig or smoothhound, could be the first shark documented to make deliberate sounds.

Paul Caiger/University of Auckland

Sharks may not be the sharp-toothed silent type after all.

The clicking of flattened teeth, discovered by accident, could be “the first documented case of deliberate sound production in sharks,” evolutionary biologist Carolin Nieder, of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, and colleagues propose March 26 in Royal Society Open Science.

Humankind has been slow in picking up on sound communication among fishes, and many of their squeaks and rumbles have come to the attention of science in captive animals. For the many bony fishes, it’s no longer a surprise to detect various chirps, hums or growls. Yet the evolutionary sister-branch, sharks and rays, built with cartilage, have been slower to get recognized for sounding off. They have remarkable senses, such as detecting slight electric fields. In 1971, however, clicking was reported among cownose rays, and has since turned up in other rays.

Nieder, who had studied dolphin hearing, was at the University of Auckland’s Leigh Marine Lab in New Zealand, dangling an underwater microphone into a tank as part of her setup to explore hearing in a small shark species called a rig (Mustelus lenticulatus). Reaching into the tank to grasp one, she heard “click…click….” After a week or so of tests, the rig still squirmed but didn’t click. Perhaps the sound was voluntary, a response to stress, she mused.

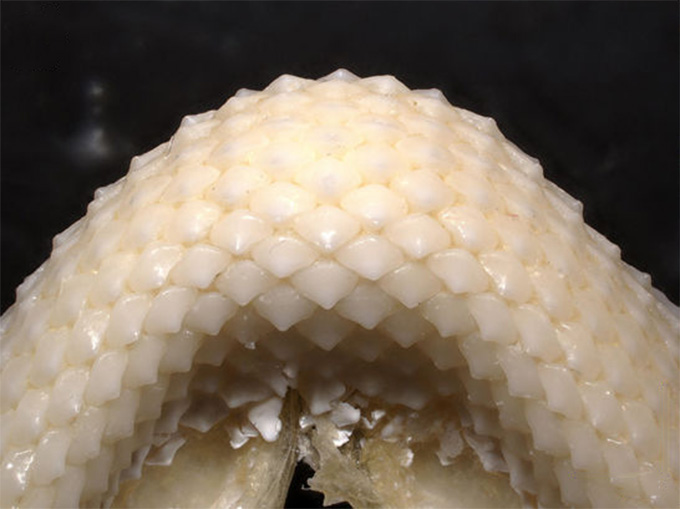

She worked with 10 sharks and recorded multiple clickity bouts, averaging about nine clicks during a 20-second grasp. The sounds may come from clacking together the flattened teeth with cusps, great for cracking crustaceans shells. Rows of these teeth emerge from gum tissue, reminding her of stones set in a mosaic.

Make some noise

In a first, researchers have recorded what could be a shark making deliberate sounds. A small shark from New Zealand, called a rig or spotted estuary smoothhound, grows rows of flattened teeth (image below) that can crack crustaceans for food and, perhaps, make communicative sounds. Evolutionary biologist Carolin Nieder discovered the sounds accidentally when she was handling a rig in a tank. Listen closely as the shark first splashes, then clicks its teeth.

Wiggling doesn’t seem important: She heard the sounds when a test shark writhed in her grasp and when it held still. She suggests that sharks click by “forceful snapping.”

The idea still needs formal testing, she cautions. What she actually measured was the hearing range of the sharks, which is restricted to below 1,000 hertz. Human hearing, in comparison, ranges up to 20,000 Hz.

Sharks are sensitive to their watery world though and can detect the tickles of changing electric fields. Yet “if you were a shark, I would need to talk a lot louder to you than to a goldfish,” she says. “The goldfish would pick up if I whisper … and the shark was like, can you speak up please?”