First Line of Defense: Hints of primitive antibodies

- More than 2 years ago

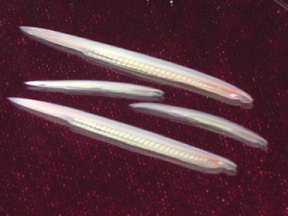

The lowly lancelet makes a living by burying itself in the sand, sticking out its mouth, and filtering tiny critters from seawater. Such feeding behavior probably exposes this common marine invertebrate to a wealth of infectious microbes. So, the finger-length animal may require something special in its immune system.

Scientists have now discovered in the animals’ guts molecules that resemble the antibodies of more-sophisticated animals. The finding may also offer a clue to how complex immune systems evolved.

Lancelets and other invertebrates wield a primitive, or innate, immune system. It can recognize the creature’s own cells and reject foreign bodies. In contrast, people and other jawed vertebrates brandish adaptive immune systems. These can mount tailor-made defensive actions by producing antibodies chemically matched to molecular motifs on invading microbes.

Scientists know little about the emergence of these sophisticated immune systems about 500 million years ago, which occurred as vertebrates evolved from jawless into jawed creatures. “Our adaptive immunity just springs into being,” comments Gregory W. Warr, an immunologist at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

To tease out the details of the transition, other researchers recently turned to lancelets, vertebrates’ closest spineless relatives. Molecular immunologist Gary W. Litman of All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Fla., and his colleagues at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa used a new technique that identifies short sequences of DNA.

The team scoured the lancelet genome for precursors to a class of genes known as variable-region, or V-region, genes. They’re responsible for the enormous range of antibody molecules in adaptive immune systems. No one had unambiguously located such genes in animals more primitive than the jawed vertebrates.

Litman’s team found small DNA sequences that resemble V-region genes. The group was surprised to find five distinct families of these sequences.

“We think that we’ve homed in on gene families that have many characters that are reminiscent of the types of genes that went on to become the diversified families of immune molecules,” including antibodies, Litman says. He and his colleagues report their findings in the December Nature Immunology.

John J. Marchalonis, a molecular geneticist at the University of Arizona in Tucson, doesn’t doubt that these lancelet genes are distantly related to V-region genes.

Still, he says, there’s no evidence that these genes mix and match, the way true V-region genes do, to encode a huge variety of antibodies. Indeed, the functions of the newly found lancelet genes remain unknown.

Marchalonis says, “It is premature [for Litman’s group] to make a strong link with adaptive-type immunity.”

Warr contends that the newly identified genes probably do represent the first diversified V-region families to be found in animals more primitive than jawed fish.

Says Warr, “There’s a possibility that [Litman’s team is] looking at a set of molecules that somehow bridge, or are related to, the border between adaptive and innate immunity.”

Litman next plans to look for novel immune genes in jawless vertebrates, such as lamprey and hagfish. “We think there is a lot of information buried in the evolutionary history,” he says.

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, please send it to editors@sciencenews.org.