Fingerprints of climate change are increasingly appearing in extreme weather

Fires, floods and vanishing sea ice are among the 2018 disasters attributed to human activity

Flash flooding on May 27, 2018, turned Main Street in Ellicott City, Md., into a river. The heavy rains throughout much of 2018 that led to the mid-Atlantic region’s floods were made more likely by human-caused climate change, scientists say.

Libby Solomon/The Baltimore Sun via AP

- More than 2 years ago

SAN FRANCISCO — Extremely low sea ice in the Bering Sea. Heavy rainfall in the mid-Atlantic United States. Wildfires in northeast Australia.

Examinations of these and 16 other extreme weather events that occurred in 2018 found that all but one were made more likely due to human-caused climate change, scientists reported December 9 at a news conference at the American Geophysical Union’s annual meeting. Insufficient observational data made it impossible to assess the influence of climate change on the one event, heavy rains in Tasmania.

The new report marks the third year in a row that scientists have identified specific weather events that they said would not have happened without human activities that are altering Earth’s climate.

The findings are part of a climate-attribution special issue, called “Explaining extreme events in 2018 from a climate perspective,” published online December 9 in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Over the 11 years that BAMS has published the special issue, it’s included 168 studies examining specific weather events. Of those, 122, or 73 percent, found that climate change likely played some role in the event, the special issue’s editor Stephanie Herring said at the news conference. In some cases, that means the event was more likely to occur due to human actions; in a few studies, researchers have concluded that the event would not have occurred without climate change.

Finding a role is becoming more common; the special issues tied to events in 2017 and 2016 found that climate change was linked to 95 percent of the events studied (SN: 12/14/17; SN: 12/11/18).

Rather than being a cause for despair, identifying humankind’s role in these events should be seen as a way to provide new data in the fight to prepare for climate change, BAMS Editor in Chief Jeff Rosenfeld said in the news conference. “Instead of stoking fear, I think having real quantifiable information like this puts that human fingerprint in terms that we can actually act [on] without getting overwhelmed.”

Below are a few of the highlights of the new report.

Historic flooding

Extreme rainfall from January through September 2018 led to flooding across Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, West Virginia and Washington, D.C. An analysis of 40 climate simulations of both historical and future climate conditions showed that the intense rainfall was 1.1 to 2.3 times more likely as a result of climate change, a team led by climate scientist Jonathan Winter of Dartmouth College reported.

To determine how the rains might be linked to changing climate, scientists first examined daily rainfall measured at 63 stations in the mid-Atlantic region from 1920 to 2018. Rainfall totals from January through September 2018 were the highest ever measured at 33 percent of the stations, the team found — and in the top three at 62 percent of the stations. That made 2018 precipitation a 1-in-99-year event.

Fierce fires

About 130 wildfires that raged across northeast Australia in November 2018 also bore the stamp of climate change, researchers say — although deconstructing the cause of the fires is complex. Multiple contributing factors likely added to the potential fuel for the fires, reports the team, led by climate scientist Sophie Lewis of the University of New South Wales Canberra in Australia. Those factors include low rainfall during the preceding spring months as well as an extreme heat wave, both linked to climate change.

Altered atmospheric circulation patterns, such as a sustained low-pressure system south of the region and an unusual westerly winds, likely made conditions more favorable to wildfires, the team reported.

Vanishing ice

Floating sea ice in the Bering Sea over the winter of 2017 to 2018 was lower than at any time in the last five decades of satellite observations, said climate scientist Walt Meier of the National Snow & Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo., who coauthored a study on climate change’s impacts on the region.

The impacts of that low Bering Sea ice extent have been well documented (SN: 3/14/19), including massive seabird die-offs (SN: 5/31/19), changes in fish populations and extensive coastal flooding in the region. But now, scientists are confirming that the lack of ice that year was the result of climate change.

Going low

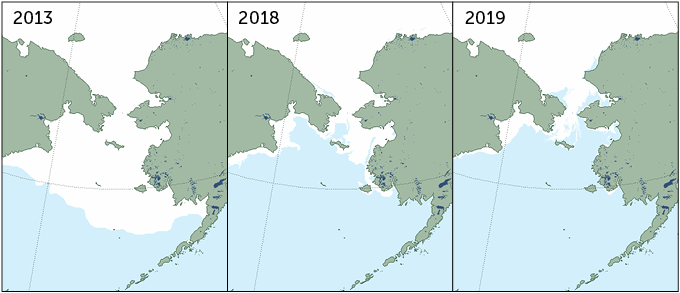

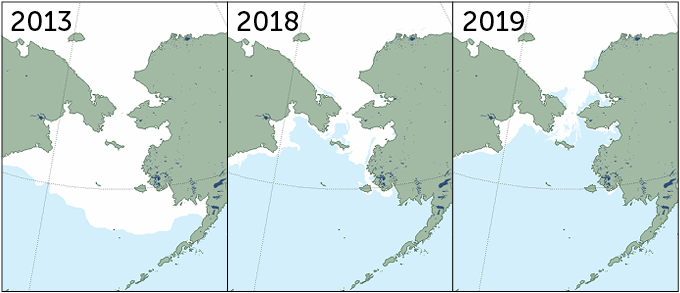

Bering Sea ice extent on April 1, 2013, (left) is in line with the average extent of the region’s sea ice over the last five decades. But on April 1, 2018, (middle) the Bering Sea was nearly ice-free. Such a low sea ice extent would have been nearly impossible without human-caused climate change, scientists say. Similarly, sea ice extent on April 1, 2019, (right) was among the lowest in the satellite record.

Shrinking ice extent in the Bering Sea

The researchers simulated how the sea ice would wax and wane from January to April in a world with no human-caused greenhouse gas emissions — and therefore with atmospheric carbon dioxide levels similar to those of 1850. The team ran 1,800 simulations of this “planet B” scenario, and found only two instances in which the minimum sea ice extent dipped down as low as the observed 2018 levels. That suggests that the observed extent would be “nearly impossible” without human-caused climate change, Meier said.

By 2050, the low sea ice extent of 2018 will become the new normal, he added. And by 2100, any years with sea ice extents matching that of 2018 will again be outliers — they’ll be unusually large.