After ancient people left their African homeland, they migrated into Asia and Europe, taking refuge from ice age conditions in areas isolated from other populations, two new reports suggest. That isolation may have prompted the evolution of new Homo species, including a mysterious Asian population dubbed Denisovans and possibly an unusual-looking humanlike group now identified in China.

Ice age asylums “are critical to understanding the expansion of H. sapiens out of Africa, the extinction of Neandertals and Denisovans, and interbreeding between these populations,” comments anthropologist Robin Dennell of the University of Sheffield, England.

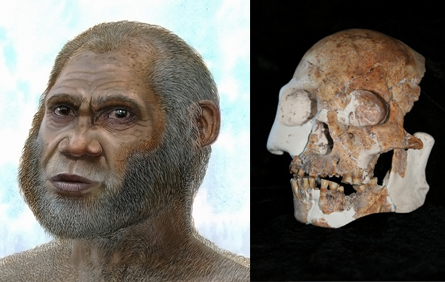

Fossils unearthed in two caves in southwestern China come from an unusual-looking line of Homo sapiens, or perhaps a previously unknown Homo species, say anthropologist Darren Curnoe of the University of New South Wales in Sydney and his colleagues. This group lived near modern-looking people between 14,300 and 11,500 years ago.

Ancient bones unearthed previously and in new digs at the Chinese caves combine features of people today with flaring cheekbones and other traits of poorly understood African Homo fossils from more than 100,000 years ago. Since this anatomically peculiar population survived alongside modern-looking people until almost 11,000 years ago, Curnoe suspects that the new fossils represent a separate Homo species that originated in Asia.

“We’re cautious about classifying these fossils, because scientists lack a satisfactory biological definition of Homo sapiens,” Curnoe says. He and his colleagues report the findings online March 14 in PLoS ONE.

Ancient people left Africa as early as 120,000 years ago, so the Chinese fossils might be those of early migrants who evolved in relative isolation for tens of thousands of years without contributing genetically to people today, Curnoe suggests.

Instead, the ancient features of the new Chinese finds might reflect interbreeding with a Stone Age, humanlike species dubbed Denisovans, remarks anthropologist Christopher Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London. Denisovans, identified from DNA taken from a single finger bone found in Siberia, interbred with humans in southeastern Asia at least 44,000 years ago (SN: 11/5/11, p. 13). Researchers regard Denisovans as close relatives of Neandertals.

In the March 16 Science, Stringer and evolutionary ecologist John Stewart of Bournemouth University, England, propose that the evolution of humans and earlier Homo species that reached Asia and Europe hinged on small populations that took refuge in ecological sanctuaries during recurring ice ages.

As in many plants and animals, climate-induced corralling of Homo groups into restricted habitats prompted the evolution of new species, most notably Neandertals and Denisovans, Stringer and Stewart hypothesize in their new work, which lays out a framework of what early human migration and evolution might have looked like.

Consider Homo heidelbergensis, a likely ancestor of Neandertals and H. sapiens that left Africa between 600,000 and 400,000 years ago. H. heidelbergensis apparently survived in livable parts of southwestern Asia during ice ages. A long-isolated H. heidelbergensis population evolved into Neandertals, Stringer suggests.

Neandertals interbred with H. sapiens around 45,000 years ago, as ancient people reached a climate-friendly part of southern Europe already populated by their evolutionary cousins, Stringer proposes. Neandertals then headed to Europe’s southwestern corner and died out by 30,000 years ago.

A still mysterious population of Asian migrants found an ice-age retreat and evolved into Homo floresiensis, Stringer says. This tiny, humanlike species, nicknamed hobbits, lived from around 95,000 to 17,000 years ago in southeastern Asia.

Climate fluctuations need not have regularly chased Stone Age folk into “safe” areas, remarks anthropologist Rick Potts of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Geological evidence suggests that H. sapiens and its African ancestors originated during volatile periods — lasting up to 300,000 years — when the climate veered from extremely rainy to bone dry every 8,000 to 12,000 years, Potts says.

Faced with constantly shifting habitats, ancient people and their precursors evolved to deal with a wide range of environments, he asserts. East Asian migrants would have adapted to ice ages rather than seeking ecological shelter.

Anthropologist David Frayer of the University of Kansas in Lawrence also doubts that cold-weather refuges stoked human evolution. Stone Age groups in Asia and Europe interbred enough, even during ice ages, to maintain H. sapiens as a widespread species that encompassed Neandertals and the newly reported Chinese individuals, Frayer argues.

Consistent with Stringer’s argument, an ancient DNA analysis published online February 23 in Molecular Biology and Evolution suggests that one portion of the Neandertal population sought ice age sanctuary in Western Europe between 70,000 and 55,000 years ago before dying out and giving way to remaining Neandertals from Eastern Europe. Geneticist Love Dalén of the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm and his colleagues found much less genetic diversity in Western European versus Eastern European Neandertals.

Such evidence may point toward refuge-driven evolution outside Africa, but much remains unknown. “Asia is huge and we know little about ancient human populations there,” Stringer says.

Back Story – Skull to skull

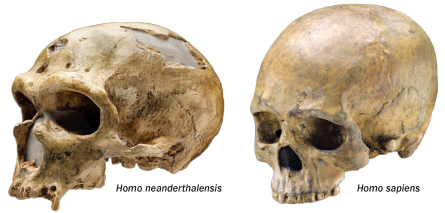

Although DNA analyses have allowed the identification of distinct hominid species like the Denisovans, human evolutionary scientists still rely largely on fossil studies to reveal differences between early human and humanlike species. A comparison of the skulls of contemporaries Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens, for example, argues that these were indeed two separate species, both thought to have evolved from the more ancient Homo heidelbergensis. Scientists look to certain key features when evaluating such fossils.

Credit: Human Origins Program, Smithsonian Institution

Credit: Human Origins Program, Smithsonian Institution

Skull – The Neandertal skull is thicker, with a round protrusion at the back of the head. H. sapiens’ skull has a more rounded dome shape.

Face – H. sapiens has a relatively flat, small face. Neandertals had a sloping face.

Braincase – The Neandertal braincase is slightly larger.

Forehead – The Neandertal forehead recedes while H. sapiens has a high, distinctive forehead.

Brow – ridges Protruding brow ridges distinguish the Neandertal.

Chin – H. sapiens has a well-developed chin.