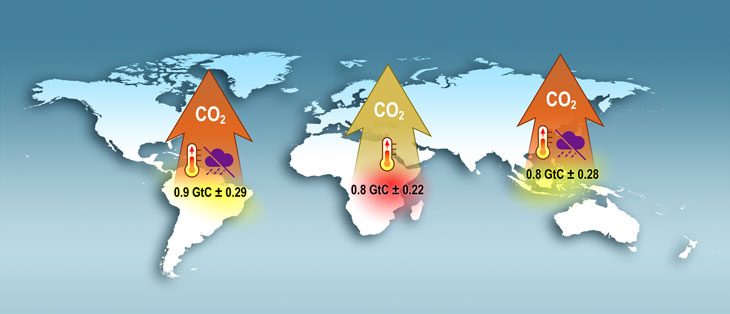

During El Niño, the tropics emit more carbon dioxide

The phenomenon creates warmer, drier conditions in some tropical regions that mimic future climate change

LOFTY LOOK NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (shown in an artist’s illustration) launched in 2014 and is giving scientists an unprecedented peek into how carbon moves between land, atmosphere, and oceans on Earth.

JPL-NASA