Domain of the dead

Stonehenge served as an elite cemetery for more than 500 years

Stonehenge, a set of earth, timber, and stone structures perched provocatively on England’s Salisbury Plain, has long invited lively speculation about its origin and purpose.

There was nothing lively about Stonehenge in its heyday, though. Ancient big-wigs used Stonehenge as a cemetery from its inception nearly 5,000 years ago until well after its large stones were put in place 500 years later, according to the directors of a 2007 investigation of the ancient site.

The new findings challenge a longstanding assumption that the deceased were buried at Stonehenge for only a 100-year window, from 4,700 to 4,600 years ago, and before the large stones—known as sarsens—were hauled in and assembled into a circle. But the new findings indicate that Stonehenge was a cemetery for at least 500 years, beginning around 5,000 years ago.

“Stonehenge was the biggest graveyard of the third millennium B.C.,” says archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson of the University of Sheffield in England. “From its beginning, it was used as a cemetery for a large number of people.” Parker Pearson directs the Stonehenge Riverside Archaeological Project, which began in 2003 and runs through 2010.

Parker Pearson and archaeologist Julian Thomas of the University of Manchester in England described their latest findings May 29 at a teleconference held by one of their funding organizations, the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C.

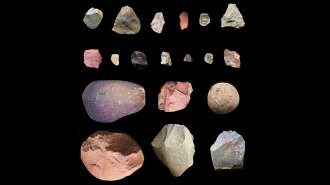

He and his colleagues obtained the first radiocarbon age estimates for cremated human remains excavated earlier at Stonehenge. These burned bones were unearthed more than 50 years ago and have been kept at a nearby museum.

The earliest cremation, a small pile of burned bones and teeth, dates from 5,030 to 4,880 years ago, about the time when a circular ditch and a series of pits were cut into the Salisbury Plain. The human remains originally lay in one of those pits, at the edge of where the circle of sarsen stones would later be placed.

An adult’s burned bones, originally found in a ditch that encircles Stonehenge, date from 4,930 to 4,870 years ago.

Remnants of a third cremation date from 4,570 to 4,340 years ago, around the time when sarsen stones first appeared at Stonehenge.

Another 49 cremation burials were unearthed at Stonehenge during the 1920s but later interred again because archaeologists at that time saw no scientific value in the bones. An estimated 150 to 240 cremated bodies were buried at Stonehenge over a span of 500 to 600 years.

Andrew Chamberlain, a biological anthropologist at the University of Sheffield who did not participate in last year’s dig, suspects that Stonehenge functioned as a cemetery for 30 to 40 generations of a single family, perhaps a ruling dynasty. In support of that hypothesis, the head of a stone mace had been buried with one set of cremated remains, Parker Pearson says. Maces symbolized authority in British prehistory.

If Stonehenge operated as a domain of the dead, the nearby village of Durrington Walls was built around the same time to accommodate the living, Parker Pearson asserts. In 2006, his team discovered remnants of this village, grouped around a timber version of Stonehenge. Stonehenge’s builders apparently lived at the site for part of each year beginning around 4,600 years ago.

Last year the researchers excavated four houses at Durrington Walls that once sat on a hillside. An especially well-preserved structure yielded a wall made of cobb, a mixture of broken chalk and chunky plaster. It’s the oldest such wall known in England, Parker Pearson says. The other houses consisted mostly of a more primitive, wattle-and-daub material.

The well-preserved house contained a few relics of everyday life, including flint tools and sharp flint chips swept into two teacup-sized holes in the corners. Imprints of a bed and dresser were visible on the floor, as well as two thick grooves where someone once knelt near an oval-shaped hearth.

The researchers also uncovered remains of several three-sided structures along a broad avenue that linked Durrington Walls to the River Avon.

Parker Pearson suspects that Durrington Walls consisted of at least 300 houses, making it the largest village of its time in northwestern Europe.

New radiocarbon dates of an antler pick used for digging indicate that the Stonehenge cursus, a 3-kilometer-long earthen enclosure framed by parallel ditches, was constructed about 5,500 years ago. The cursus contains no bones or artifacts. It may have been either a sanctified or a cursed spot that people avoided, Thomas suggests. Analyses indicate that this monument was reworked several times from between 5,500 and 4,000 years ago.

“This landscape had symbolic importance that was maintained over a long period of time,” Thomas says.