The way the coronavirus messes with smell hints at how it affects the brain

Conflicting data leave big questions about how the virus operates

A bout with COVID-19 can block the ability to smell, but the way the coronavirus does this is still up for debate.

Taylor Deas-Melesh/Unsplash

- More than 2 years ago

The virus responsible for COVID-19 can steal a person’s sense of smell, leaving them noseblind to fresh-cut grass, a pungent meal or even their own stale clothes.

But so far, details remain elusive about how SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, can infiltrate and shut down the body’s smelling machinery. One recent hint comes from a young radiographer who lost her sense of smell. She had signs of viral infection in her brain. Other studies, though, have not turned up signs of the virus in the brain.

Contradictory evidence means that no one knows whether SARS-CoV-2 can infect nerve cells in the brain directly, and if so, whether the virus’s route to the brain can sometimes start in the nose. Understanding how people’s sense of smell is harmed (SN: 5/11/20), a symptom estimated to afflict anywhere between 20 and 80 percent of people with COVID-19, could reveal more about how the virus operates.

One thing is certain so far, though: The virus can steal the sense of smell in a way that’s not normal.

“There’s something unusual about the relationship between COVID-19 and smell,” says neuroscientist Sandeep Robert Datta of Harvard Medical School in Boston. Colds can prevent smelling by stuffing the nose up with mucus. But SARS-CoV-2 generally leaves the nose clear. “Lots of people are complaining about losing their sense of smell when they don’t feel stuffed up at all,” Datta says.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

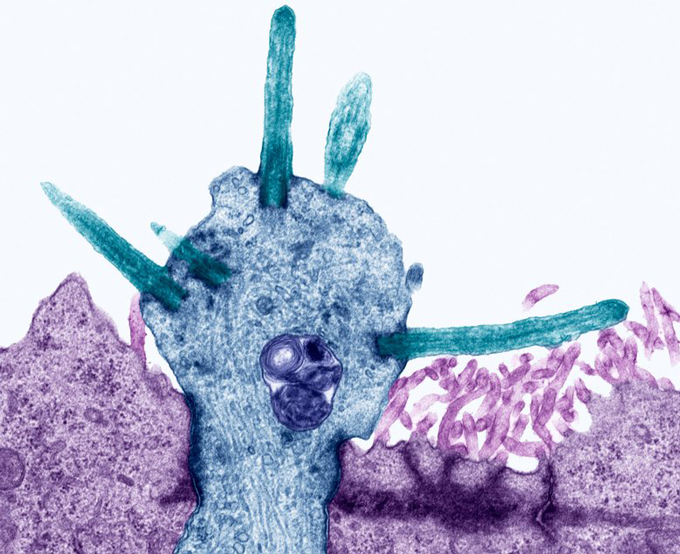

Recent studies have begun to identify the cells in the olfactory epithelium, a slender sheet of tissue that lines part of the nasal cavity, that seem vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Smell-supporting cells called sustentacular cells are likely targets, scientists report in two new papers, one in ACS Chemical Neuroscience and the other posted at bioRxiv.org, a repository for research that hasn’t been peer-reviewed by other scientists.

“Obviously we don’t know for sure, but at this point, it appears that the smell losses associated with SARS-CoV-2 are probably due to its impact on the supporting cells, the non-neuronal cells, in the olfactory epithelium,” says sensory psychologist Beverly Cowart of Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, who was not involved in either study.

Datta and his colleagues performed experiments that looked in nose cells — support cells and the nerve cells that send messages to the brain — from both mice and people for signs of ACE2, a key protein that SARS-CoV-2 latches onto to break into cells (SN: 2/3/20). Molecular signals indicating that the ACE2 protein was going to be made were found in nose support cells, including sustentacular cells, the researchers found. These cells are thought to help maintain precise concentrations of chemicals in the nose. These mixtures allow nerve cells called olfactory receptor neurons to fire off smell signals to the brain.

But ACE2 was conspicuously absent from these neurons, the researchers initially reported March 28 at bioRxiv.org. In a revised version of the paper posted May 18, Datta and his colleagues bolstered that evidence, including a direct detection of ACE2 protein itself in support cells, but not in neurons.

Another study, published May 7 in ACS Chemical Neuroscience, found similar results in mice. Sustentacular cells had ACE2 protein, Rafal Butowt of Nicolaus Copernicus University in Bydgoszcz, Poland and colleagues reported. But neurons didn’t have ACE2. The results imply that SARS-CoV-2 can’t infect olfactory receptor neurons themselves, or if it can, that it happens very rarely, Butowt says, though more work is needed to be sure. (Datta, for now, remains agnostic on whether neurons can become infected.)

If SARS-CoV-2 doesn’t target olfactory receptor neurons directly, that could be good news. That’s because, as far as neurons go, olfactory receptor neurons are unusual — they live outside of the brain, but keep one foot inside it. This precarious straddle renders them — and the brain itself — vulnerable to infections. Other pathogens, including a different coronavirus and a brain-eating amoeba (SN: 7/20/15), can use these neurons, and their message-sending axons that reach the brain, as conduits to the brain. “The big open question is whether or not the SARS-CoV-2 virus can move along olfactory neuronal axons to the brain,” Butowt says.

Other research suggests that the virus is able to invade the brain. In one study, scientists put the virus in the noses of mice engineered to have the human form of ACE2 protein. Later, the virus had spread to the mice’s lungs, trachea and brains, scientists report May 26 in Cell Host & Microbe.

“That’s the right experiment to do,” Datta says. But he notes that some key details, such as where the neurons are in the brain, and how many of them are infected, are not reported in depth in the paper. It’s also not clear how the virus actually got to the brain.

Studies on human brains are mixed. In postmortem studies of 10 people who died of COVID-19, none had SARS-CoV-2 in cerebrospinal fluid, suggesting that the virus wasn’t in their brains. The paper, published May 21 in JAMA, didn’t include whether these people had lost their ability to smell.

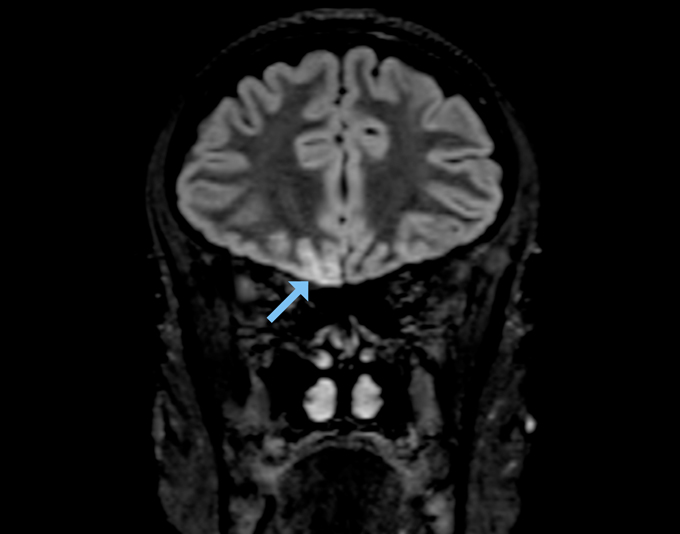

But an MRI of a young woman’s brain turned up signs of SARS-CoV-2 infection in several areas involved in smell, including the olfactory bulb and a part of the brain called the right gyrus rectus, which helps process smell signals, scientists report May 29 in JAMA Neurology. The woman, who worked as a radiographer in a ward treating COVID-19 patients, had completely lost her sense of smell, but had only mild symptoms otherwise. Based on these findings, Letterio Politi, a radiologist at Humanitas Clinical and Research Hospital and University in Milan, Italy, and colleagues suspect that the virus moved into the woman’s brain from her nose.

Nerve cells aren’t the only potential vehicle. Studies have shown that the coronavirus can infect pericytes, cells that wrap around blood vessels and help control flow. In the brain, pericytes help maintain the blood-brain barrier, which is designed to keep pathogens out. A breach there could let the virus into the brain. For now, gaps in basic knowledge and a dearth of documented cases leave open the question of whether the coronavirus reaches the brain, and if so, how. More studies on tissue that comes from infected people are urgently needed, says Datta. “We need much more information than we have now.”