How COVID-19 may trigger dangerous blood clots

Clots may stem from immune cells that cast nets that trap red blood cells and platelets

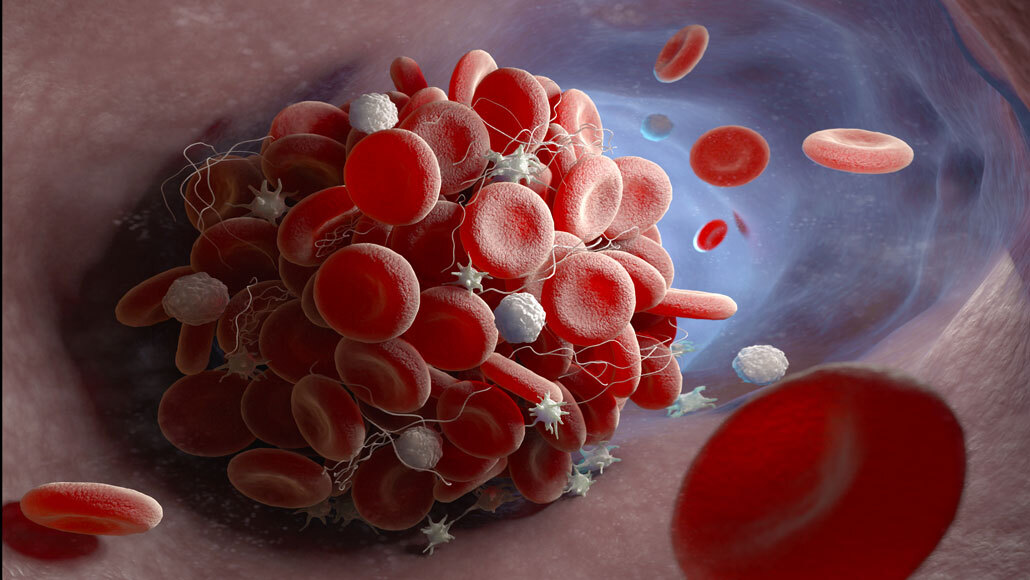

A study finds that antibodies in some COVID-19 patients may trigger a series of events that lead to blood clots (illustrated).

iLexx/iStock/Getty Images Plus

- More than 2 years ago

Some of COVID-19’s dangerous blood clots may come from the immune system attacking a patient’s body rather than going after the virus, a new study suggests.

It’s known that excessive inflammation from an overactive immune response can spur the clots’ formation in severely ill patients (SN: 6/23/20). Now researchers are teasing out how. Some of that clotting may come from auto-antibodies that, instead of recognizing a foreign invader, go after molecules that form cell membranes. That attack may prompt immune cells called neutrophils to release a web of genetic material geared at trapping virus particles outside of the cells.

“Presumably in the tissues, this is a way to control infections,” says Jason Knight, a rheumatologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “But if you do it in the bloodstream, it’s very triggering of thrombosis,” or clotting.

That may be what happens in some COVID-19 patients, Knight, cardiologist Yogen Kanthi of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., and their colleagues report November 2 in Science Translational Medicine. With COVID-19, blood clots in the lungs have been a significant cause of death, Kanthi says. And some blood clots may form when the webs trap red blood cells and platelets, creating a sticky clump that can clog blood vessels.

“These are very intriguing findings,” says Jean Connors, a clinical hematologist at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston who was not involved in the work. “There has been a lot of speculation about what the presence of [the auto-antibodies] means and whether they have any pathogenic role.”

Studies have revealed that some auto-antibodies can interfere with the immune response to viruses (SN: 9/25/20). Some preliminary work further suggests that auto-antibodies that bind to a variety of targets in the host may be a common feature in severely ill COVID-19 patients.

Auto-antibodies that recognize cell membrane molecules called phospholipids can cause an autoimmune disease called antiphospholipid syndrome, or APS. In people with APS, the auto-antibodies can activate clot-forming cells, putting those patients at higher risk of blood clot formation.

These detrimental antibodies can also appear during bacterial or viral infections such as strep throat or HIV. But it’s difficult to determine whether the antibodies lead to blood clotting during infection, Connors says, especially because some healthy people might also have low levels without forming clots.

Severely ill COVID-19 patients can have high levels of neutrophils, and some have phospholipid-binding antibodies in their blood. So Knight and his colleagues wondered whether the antibodies might be causing neutrophils to release traps that trigger clotting.

Of 172 hospitalized COVID-19 patients included in the study, more than half had auto-antibodies that recognized one of three different types of host phospholipids. The presence of those immune proteins was linked to having high levels of neutrophils in the blood and proteins that suggested the neutrophils had joined the fight. And when the researchers mixed auto-antibodies taken from six COVID-19 patients with neutrophils grown in lab dishes, the neutrophils cast their nets. What’s more, when the team injected patient auto-antibodies into mice, the rodents formed blood clots — hinting that clotting in people could be triggered by the immune proteins.

It’s unlikely that phospholipid auto-antibodies are the whole story, says Thomas Kickler, a hematologist at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine who was not involved in the work. Other inflammatory immune responses also trigger clots, so auto-antibodies are probably one piece of the puzzle. Of the people in the study, for instance, 11 patients developed blood clots, and only half of them had the auto-antibodies.

More work needs to be done to directly link the immune proteins to clotting in people with COVID-19, Connors says. But the study does suggest one possible mechanism for how the clots form.

Removing the problematic antibodies through a process called plasmapheresis, in which the liquid part of blood is filtered, could help critically ill COVID-19 patients who don’t respond to other therapies to stop clotting, Knight says. That plasma, however, would also contain antibodies that recognize and attack the coronavirus. So doctors may need to give those patients lab-made immune proteins to fight the virus if it is still replicating in their body.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.