Although 4-year-olds’ concept of time often seems to consist solely of what they want right now, the passage of time still moves them. By that age, kids already mark time by referring to physical distances, say psychologist Daniel Casasanto of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues.

Abstract concepts such as how time works stem from youngsters’ real-world perceptions and behaviors, not from cultural rules or metaphorical language used in speech, Casasanto’s group proposes in an upcoming Cognitive Science.

“We find that time representations depend on space just as strongly in 4-year-olds as in 10-year-olds, even though 4-year-olds have very little experience using space-time metaphors in language,” Casasanto says.

By age 10, children have heard and spoken many spatial metaphors for time, such as “a long test” and “moving up an appointment.”

Casasanto previously reported that adults estimate the amount of time it takes for lines to lengthen across a computer screen based on how far the lines travel. If two lines expand to different lengths over the same time period, volunteers judge the shorter line to have moved for less time than it actually did and the longer line to have moved for more time than it actually did (SN: 10/25/08, p. 24).

But timing has no such effect on estimates of distance: Participants don’t let differences in the amount of time that lines extend across a screen affect their judgments of line length.

Casasanto theorizes that spatial knowledge organizes time perception far more than the other way around.

In the new study, a comparable sensitivity to distance cues when making time estimates appeared in 99 children recruited from kindergartens and elementary schools in Thessaloniki, Greece.

Casasanto’s team first confirmed that children of all ages could identify the longer of two lines shown on a computer screen and could determine which of two simultaneously displayed cartoon snails bounced up and down for more time.

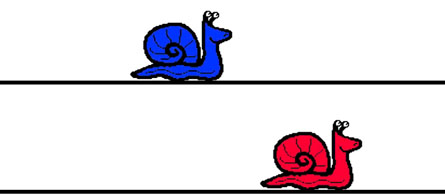

Each child then viewed three different movies showing pairs of cartoon snails, one red and the other blue, racing from left to right on parallel tracks. Snails traveled either different distances in the same time spans, different distances in different time spans or the same distance in different time spans.

Snails traversed either 400 or 600 pixels, taking either 4 seconds or 6 seconds to do so.

Regardless of age, children relied heavily on the distance traveled by each snail when trying to estimate how long the animals took to reach their destinations. In one example, a snail that crawled farther than its rival during a 4-second race was frequently estimated to have moved for more time than its opponent.

But children typically ignored the amount of time each of a pair of snails had moved when determining whether the competitors had stopped at the same spot.

The children’s native tongue was Greek, a language in which speakers usually refer to time duration without using distance words, Casasanto notes. The researchers could ask the children about time durations without using possibly confusing spatial metaphors.

Casasanto’s findings also fit with new evidence that mental time travel triggers physical movement corresponding to a concept of time’s direction, remarks psychologist Lynden Miles of the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. Adults told to think about past experiences swayed backward, whereas others told to think about the future swayed forward, Miles and his colleagues report in an upcoming Psychological Science. During 15-second trials, standing volunteers swayed as much as 3 millimeters.

Snails’ Paces When shown movies of two snails crawling along parallel paths for different distances or amounts of time, children judged the amount of time a snail took to make its trip based on how far the snail went. That’s a sign that the concept of time grows out of spatial knowledge, researchers propose. In this movie clip, young volunteers watched a blue snail crawl a longer distance over a shorter time span than a red snail.

Credit: Daniel Casasanto of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands