Changing climate:10 years after An Inconvenient Truth

By Thomas Sumner April 8, 2016

More than 25 years before the star-studded Los Angeles premiere of An Inconvenient Truth, glaciologist Lonnie Thompson was about as far away from the red carpet as possible. It was 1978, and high in the rugged Andes, Thompson and fellow scientists were witnessing the first glimpses of a pending worldwide disaster. Rising temperatures were melting ancient titans of ice and snow. Mammoth glaciers were disappearing at unprecedented rates and withering to the smallest sizes in millennia. The delicate balance of Earth’s climate was upset.

As research mounted, scientists around the world from fields as diverse as chemistry and astronomy were coming to grips with a newfound truth: Carbon dioxide spewed by fossil fuel burning and other greenhouse gases were warming the world at an alarming rate, potentially threatening the health and livelihoods of millions of people. Despite the gravity and urgency of their findings, the scientists’ warnings fell mostly on deaf ears for years.

Until 2006. Six years after his unsuccessful presidential campaign, Al Gore reentered the national spotlight to release An Inconvenient Truth, which heavily featured Thompson’s mountaintop research. Thompson missed the premiere of the documentary because he was gearing up to return to South America’s vanishing ice. But the film did what he and other researchers had been unable to do: “It got climate change on the radar,” Thompson says. Last December, Gore was on hand in Paris as 195 nations committed to the most ambitious pledge yet to fight back against climate change and curb carbon emissions (SN: 1/9/16, p. 6).

In the 10 years since the movie sparked increased public discussion, climate scientists have made major advances. More observations, faster climate-simulating computers and an improved understanding of the planet’s inner workings now provide a clearer window on how Earth’s climate will change.

Some of the bold forecasts of the 2006 movie are holding, and others are on an accelerated track. A few of the most dire warnings need revising, says Thompson, at Ohio State University in Columbus. And plenty of questions remain. In a controversial paper in March in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, researchers argued that the effects of climate change could be even more severe and sudden than current predictions.

While a lot has changed, the fundamental understanding of climate change, dating back to the 19th century recognition that carbon dioxide warms the planet, has held strong, he says.

“The physics and chemistry that we’ve known about for over 200 years is bearing out,” Thompson says. “We’ve learned so much in the last 10 years, but the fact that the unprecedented climate change of the last 40 years is being driven by increased CO2 hasn’t changed.”

The far-reaching effects of climate change — from ocean acidification to disrupted ecosystems — are too numerous to examine all at once. But below are a few of the areas where climate scientists have made significant progress since 2006.

Above, video: Warming is altering Earth’s landscape, such as via accelerated ice loss on this Norwegian glacier. Alternate photo: Scientists with NASA’s ICESCAPE mission investigate the effects of climate change on Arctic ecosystems.

Video: Incredible Arctic/Shutterstock; photo: Kathryn Hansen/NASA

Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005. The storm’s destruction, compounded by failed levees, sparked concerns that climate change could have been at least partially responsible.Jocelyn Augustino/FEMA

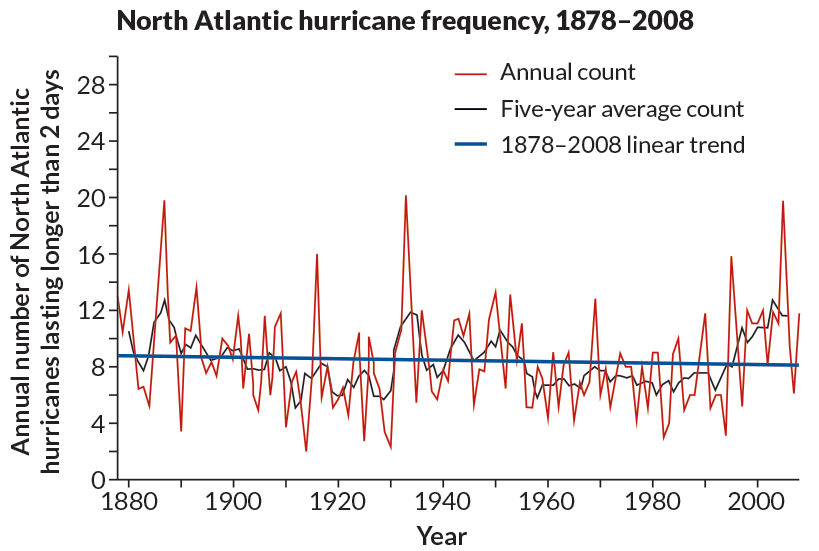

Hurricanes

2006: The warming ocean could fuel more frequent and more intense Atlantic hurricanes.

2016: Hurricane frequency has dropped somewhat; hurricane intensities haven’t changed much — yet.

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast. Floodwaters covered roughly 80 percent of New Orleans, 1,836 people died, hundreds of thousands became homeless and the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record was far from over. As the last storm fizzled, damages had reached $160 billion, meteorologists had run through the alphabet of preselected storm names and many people, including Gore, were indicting global warming as a probable culprit.

“Hurricanes were the poster child of global warming,” says Christopher Landsea, a meteorologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Hurricane Center in Miami. “In reality, it’s a lot more subtle than that.”

Tropical cyclones, such as Atlantic hurricanes, are stirred up where seawater is warmer than the overlying air. Because climate change raises ocean temperatures, it made sense that such storms could strike more often and with more ferocity. A closer look at hurricanes past and future suggests, however, that the relationship between warming and hurricanes is less clear-cut.

STEADY STORMS The record-smashing 2005 hurricane season raised concerns that storms were becoming stronger and more frequent. Yet, a closer look at the long-term trends revealed that Atlantic hurricane frequency has not significantly changed since 1878.Source: C. Landsea/NHC/NOAA

Several studies in the mid-2000s examining the history of Atlantic hurricanes pointed to an overall rise in the number of 20th century storms in step with warming sea surface temperatures. Scrutinizing those numbers, Landsea uncovered a problem: Hurricane-spotting satellites date back only to 1961’s Hurricane Esther. Before then, storm watchers probably missed many weaker, shorter-lived storms. Taking this into account, Landsea and colleagues reported in 2010 that the number of annual storms has actually decreased somewhat over the last century.

That decrease could be explained by climate factors other than rising sea surface temperatures. Changes in atmospheric heating can increase the variation in wind speed at different elevations, known as wind shear. The shearing winds rip apart burgeoning storms and decrease the number of fully formed hurricanes, researchers reported in 2007 in Geophysical Research Letters.

The overall frequency of storms, however, is less important than the number of Katrina-scale events, says Gabriel Vecchi, an oceanographer at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, N.J. Category 4 and 5 storms, the most violent, make up only 6 percent of U.S. hurricane landfalls, but they cause nearly half of all damage. Vecchi and colleagues used the latest understanding of how hurricanes form and intensify to forecast how the storms will behave under future climate conditions.

LANDFALL Hurricane Katrina slammed into Louisiana in August 2004. The storm devastated the state and flooded much of New Orleans.Radar data from NWS New Orleans and processed by the National Climatic Data Center

The work, published in 2010 in Science, predicted that the frequency of Category 4 and 5 storms could nearly double by 2100 due to ocean warming, even if the overall number of hurricanes doesn’t rise. At present, however, climate change’s influence on hurricanes is probably too small to detect, Vecchi says, adding that Katrina’s wrath can’t be blamed on global warming.

Future hurricanes will cause more damage, Landsea predicts, whether or not there’s any change in storm intensity. Rising sea levels mean floodwaters will climb higher and reach farther inland. Hurricane Sandy, which stormed over New Jersey and New York in October 2012, had weakened by the time it reached the coast. But it drove a catastrophic storm surge into the coastline that caused about $50 billion in damages. If sea levels were higher, Sandy’s surge would have reached even farther inland and damage could have been much worse.

Many vulnerable areas such as St. Petersburg, Fla., are woefully underprepared for threats posed by storms at current sea levels, Landsea warns. Higher sea levels won’t help. “We don’t need to invoke climate change decades down the line — we’ve got a big problem now,” he says.

“Hurricanes were the poster child of global warming. In reality it’s a lot more subtle than that.”

Researchers have directly monitored Atlantic circulation, which includes the Gulf Stream, since the 2004 deployment of the RAPID array (shown). Direct measurements suggest that the circulation may be slowing down.National Oceanography Centre (UK)

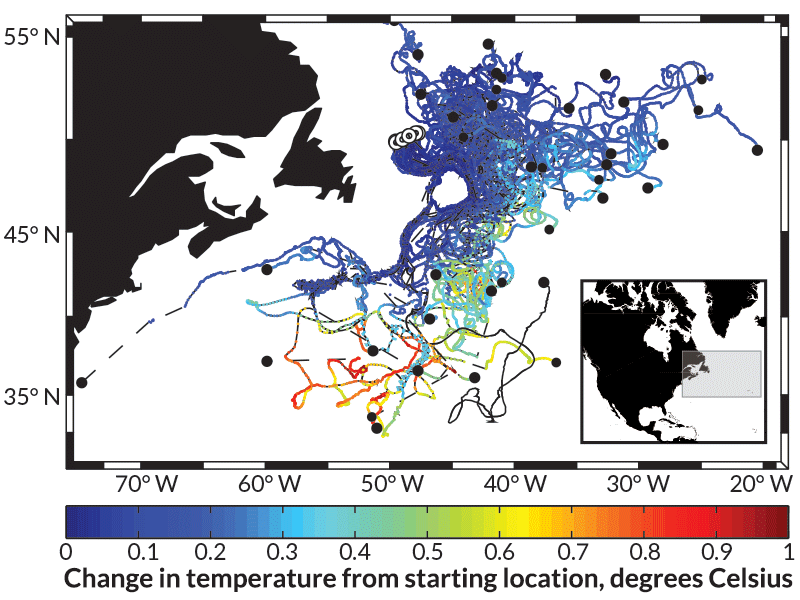

Ocean circulation

2006: Freshwater flowing into the North Atlantic could shut down the ocean conveyor belt that shuttles warm water toward Western Europe.

2016: The ocean conveyor belt may already be slowing, but it’s not much of a conveyor belt at that.

Last year may have been Earth’s hottest on record (SN: 2/20/16, p. 13). But for one small corner of the globe, 2015 was one of the coldest. Surface temperatures in the subpolar North Atlantic have chilled in recent years and, oddly enough, some research suggests global warming is partly responsible.

An influx of freshwater from melting glaciers and increasing rainfall can slow — and possibly even shut down — the ocean currents that ferry warm water from the tropics to the North Atlantic. About 10 years ago, scientists warned of a possible abrupt shutdown of this “ocean conveyor belt.” After years of closely monitoring Earth’s flowing oceans, researchers say a sudden slowdown isn’t in the cards. Some researchers report that they may now be seeing a more gradual slowing of the ocean currents. Others, meanwhile, have discovered that Earth’s ocean conveyor belt may be less of a sea superhighway and more of a twisted network of side roads.

The consequences of a sea current slowdown won’t be anywhere near as catastrophic as the over-the-top weather disasters envisioned in the 2004 film The Day After Tomorrow, says Stephen Griffies, a physical oceanographer at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. “The doomsday scenario is overblown, but the possibility of a slowing down of the circulation is real and will have important impacts on Atlantic climates,” Griffies says.

EVERY WHICH WAY Tracking the motion of floating markers dropped into the northwest Atlantic (white-rimmed circles), researchers found that the idea of an ocean conveyor belt is overly simplistic. The markers quickly split up, ending up in many different destinations (solid circles).Amy S. Bower et al/Nature 2009

The Atlantic mixing that feeds the currents is powered by differences in the density of seawater. In the simple ocean conveyor-belt model, warm, less-dense surface water flows northward into the North Atlantic. Off Greenland, cold, denser water sinks into the deep ocean and flows southward. This heat exchange, known as the Atlantic overturning circulation, helps keep European cities warmer than their counterparts elsewhere in the world.

Ten years ago, scientists knew from past changes in Earth’s climate that temperature shifts can disrupt this density balance. Freshwater from the shrinking Greenland ice sheet and increased rainfall make the North Atlantic waters less dense and therefore less likely to sink. Investigations into Earth’s ancient climates show that the overturning circulation weakened around 12,800 years ago, probably causing cooling in Europe and sea level rise along North America’s East Coast, as piled-up water in the north sloshed southward.

Tracking sea surface temperatures, researchers reported last year that the Atlantic overturning circulation significantly slowed during the 20th century, particularly after 1970. Comparing the recent slowdown with past events, the researchers reported in March in Nature Climate Change that the rapid weakening of the circulation is unprecedented in the last 1,000 years.

That result isn’t the final word, though, says Duke University physical oceanographer Susan Lozier. Scientists have directly measured the speed of the ocean circulation only since the deployment of a network of ocean sensors in 2004. Earlier Atlantic circulation speed changes have to be gleaned from less reliable indirect sources such as sea surface temperature changes. “If you look at the most recent results, there’s a decline, yes,” she says. “But we can’t say that’s part of a long-term trend right now.” And effects on Europe’s climate could be masked by other factors.

Another challenge is that over the last 10 years, “the ocean conveyor-belt model broke,” Lozier said in February at the American Geophysical Union’s Ocean Sciences Meeting in New Orleans. From 2003 through 2005, she and colleagues tracked the movements of 76 floating markers dropped into the North Atlantic and pulled around by ocean waters. If the model was right, these markers should have traveled along the southward-flowing part of the conveyor belt. Instead, the markers moved every which way, the researchers reported in 2009 in Nature.

“We went from this simple ribbon of a conveyor belt to a complex flow field with multiple pathways,” Lozier says. Determining past and possible future effects of climate change on ocean currents will require more measurements and a better understanding of how the ocean truly flows, she says.

Even if the overturning circulation cuts out completely, the resulting cooling effect will probably be short-lived, Griffies says. “At some point, even if the circulation collapses, it would only be 10 or 20 years before the global warming signal would overwhelm that cooling” in Europe, he says. “This is not going to save us from a warmer planet.”

Drought conditions worsened by climate change helped fuel the civil unrest that led to 2011’s Syrian civil war. Global security experts worry that continuing climate change will help spark more conflicts.Christiaan Triebert/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

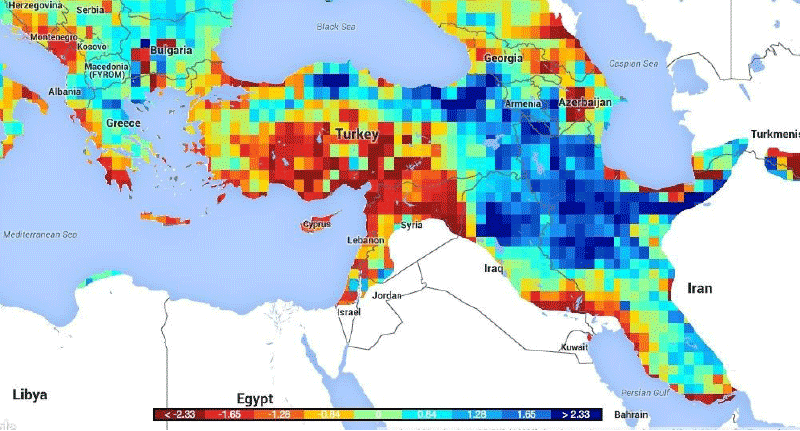

Drought, Climate and Conflict

2006: Climate change exacerbated droughts that contributed to regional conflicts, such as the war in Darfur.

2016: Drought conditions worsened by climate change helped spark the Syrian civil war.

Following escalating unrest and a wave of demonstrations across the Arab world, a bloody civil war broke out in Syria in 2011. The ongoing conflict sparked an international crisis and has left hundreds of thousands of people dead and millions more displaced. While the root cause of the conflict centered on clashes between the Syrian government and its people, multiple studies argue that climate change helped stoke the flames of rebellion.

Mounting evidence from around the world has indicted climate change in several recent severe droughts from Syria to California. Computer simulations and direct measurements of weather patterns show that climate change can redirect the paths of rainstorms and cause higher temperatures that dry out soil.

The recent Eastern Mediterranean drought was the most extreme in 900 years, new research suggests. Continuing drought conditions (red) may have contributed to the unrest that preceded the Syrian Civil War. Conditions shown here are for late 2015.NASA

In March 2015 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers estimated that decades-long shifts in Syria’s rainfall and temperatures doubled or even tripled the severity of the three-year drought that preceded the Syrian civil war. Using tree rings, a separate group reported this March in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres that 1998 through 2012 was the driest period in the Eastern Mediterranean since at least 1100.

The recent drought upset regional food security, prompted a mass migration into urban areas and emboldened anti-government forces, 11 retired U.S. admirals and generals wrote in a 2014 report published by CNA, a nonprofit research and analysis organization in Arlington, Va. The clash joins another conflict partly pinned on climate change: the war in Darfur, which broke out in 2003 following a decades-long drop in regional rainfall.

Since the 1970s, droughts have become longer and more severe across the globe, and scientists expect that trend to continue. Dwindling agricultural production in certain high-population areas such as parts of Africa could lead to food shortages that spark refugee crises, the report warned.

“We see more clearly now that while projected climate change should serve as a catalyst for change and cooperation, it can also be a catalyst for conflict,” the retired admirals and generals wrote.

Since the 1970s, droughts have become longer and more severe across the globe and scientists expect that trend to continue.

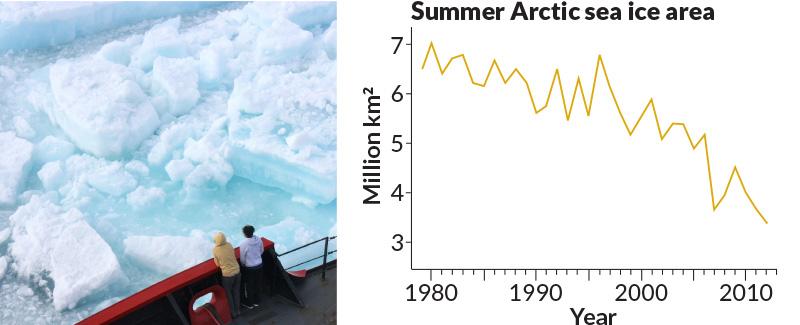

The minimum extent of Arctic sea ice has shrunk substantially since 1979. Shrinking sea ice can have both regional and global impacts for climate and ecosystems.NASA Scientific Visualization Studio

Arctic Ice

2006: The Arctic could see its first sea ice–free summers in the next 50 to 70 years.

2016: Arctic summer sea ice may disappear as early as 2052.

The top of the world could see its first iceless summer roughly a decade sooner than thought in 2006, according to a 2015 report (SN Online: 8/3/15). Simulating how sea ice interacts with the ocean using the latest understanding of how sea ice and climate interact, scientists estimated that the North Pole will be ice-free around 2052, nine years earlier than previous simulations suggested. Last year saw the fourth smallest footprint of summer sea ice in the Arctic on record. Ice-free Arctic summers would open the region to shipping and could affect climates elsewhere by redirecting the winds that circle the North Pole, the researchers wrote. The loss of reflective sea ice could also hasten warming as the dark ocean absorbs more sunlight. Newly open passages may also allow mingling of animals from formerly separated habitats (SN: 1/23/16, p. 14).

OPEN WATER Rising temperatures in the Arctic have dwindled the extent of summer sea ice, like that seen at left, taken from the deck of a research ship in July 2011. Since 1979, the minimum summer sea ice extent has decreased more than 7.5 percent per decade.Source: NSDIC; Image: Kathryn Hansen/NASA

The top of the world could see its first iceless summer almost a decade sooner than thought a decade ago

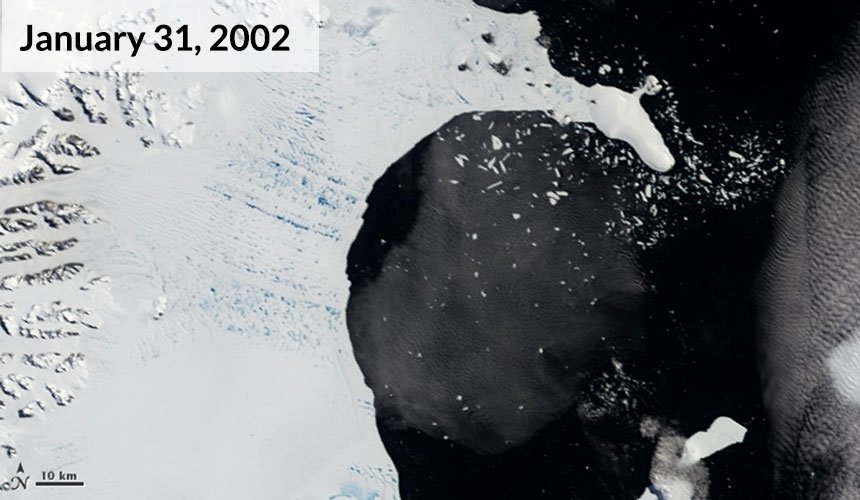

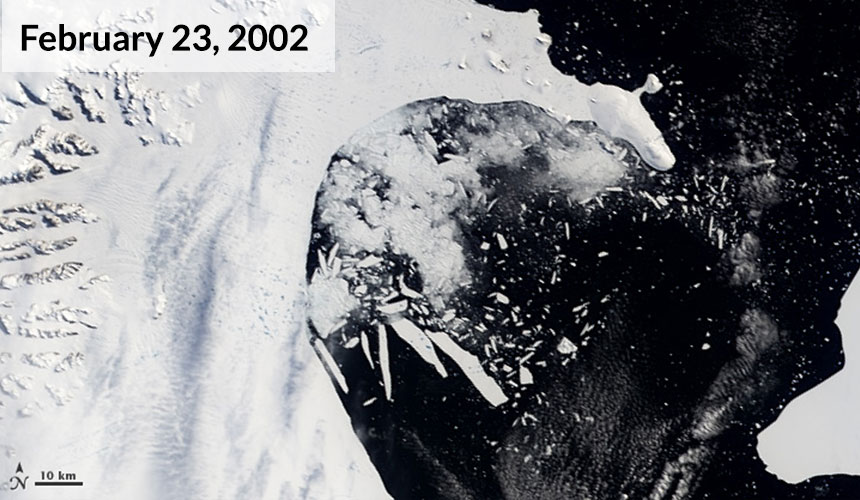

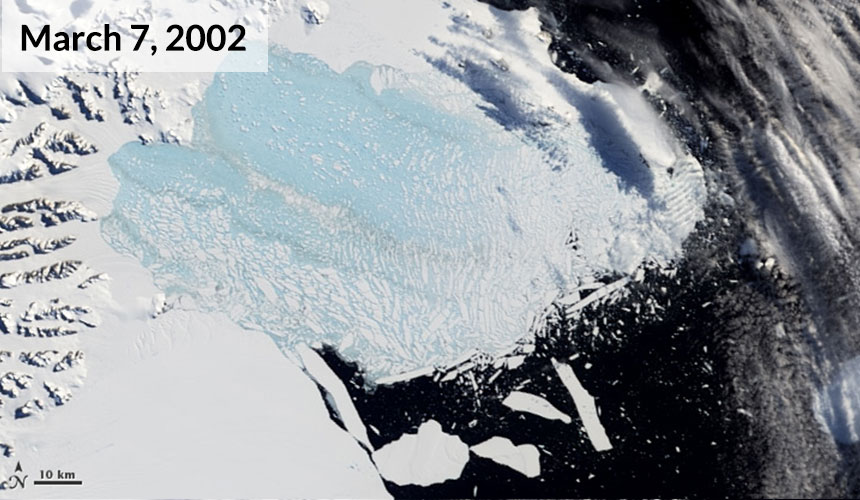

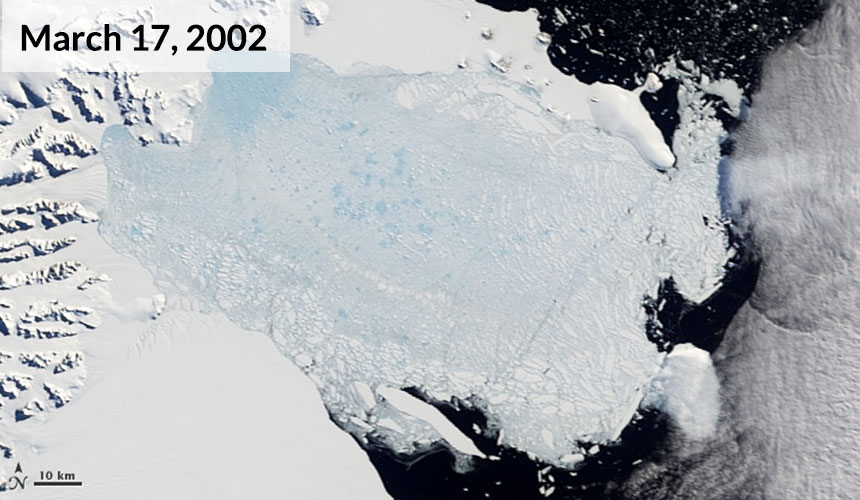

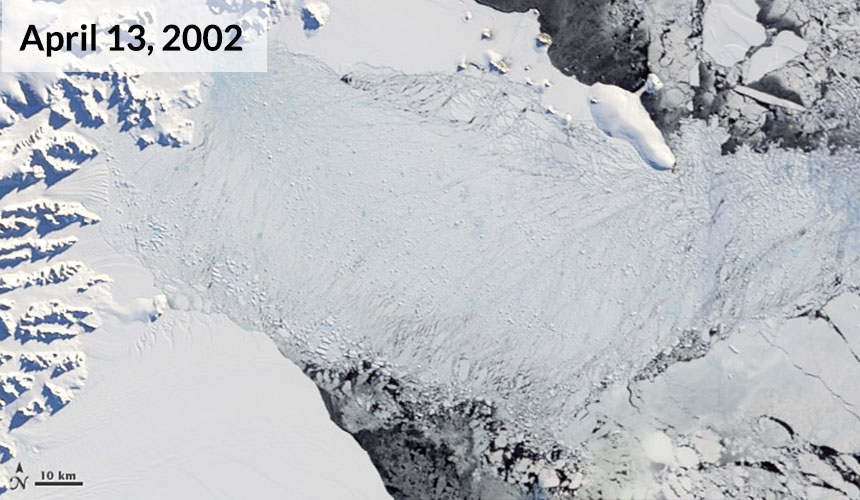

Antarctica’s Larsen B Ice Shelf collapsed into hundreds of icebergs in 2002, speeding the melt of its tributary glaciers.Ted Scambos/National Snow and Ice Data Center

Antarctic Ice Sheet

2006: Rising temperatures are warming the Antarctic and melting the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

2016: The West Antarctic Ice Sheet could cross a point of no return.

In 2002, an ice behemoth crumbled. Antarctica’s Larsen B Ice Shelf, after 12,000 years of frozen stability, collapsed. The breakdown rapidly shattered 3,250 square kilometers of ice — an area about the size of Rhode Island (SN: 10/18/14, p. 9).

“Larsen B was a real wake-up call,” says Maureen Raymo, a marine geologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y. “It was like, ‘whoa, this ice shelf didn’t just slowly retreat on its edge — the whole thing just collapsed catastrophically over the course of two weeks.’ ”

FAREWELL, ICE As Antarctica’s ice melts, warm seawater will flow through low-lying channels currently filled with ice and accelerate further melting. An ice-free Antarctica (beige area) would leave less land above sea level (blue shows footprint of current continent).Mark Helper/Univ. of Texas at Austin

Now with 10 years of on-the-ice research, scientists warn that the rest of the West Antarctic ice could share a shockingly swift fate unimaginable a decade ago. The ice sheet’s collapse would raise global sea levels by about 3 meters (SN: 6/14/14, p. 11).

Ice shelves line about 45 percent of the Antarctic coast and help slow the flow of the continent’s ice into the sea. For healthy ice shelves, the flow of ice from inland balances losses from melting and icebergs snapping off the shelf’s seaward edge. Rising temperatures below and above the ice can fracture and thin the ice, upsetting this balance.

The loss of just a few ice shelves in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could destabilize the whole region, according to new research by climate scientists Anders Levermann and Johannes Feldmann of the University of Potsdam in Germany. In a computer simulation, the researchers found that the loss of a few key ice shelves around Antarctica’s Amundsen Sea would trigger a domino effect. Seawater would flow into the flanks of other ice and expedite melting. Such a collapse would annihilate the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet within hundreds to thousands of years, they predict.

Once started, this chain reaction would be unstoppable, the researchers reported last November in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Even if global temperatures return to normal, the ice sheet would still be doomed, according to the simulation. In 2014, researchers reported that one of those keystone ice shelves, the Thwaites Glacier, is on track to recede past an underwater ridge currently stalling its retreat and undergo catastrophic collapse in as few as two centuries.

Exactly what magnitude of warming will push the West Antarctic Ice Sheet past the point of no return remains uncertain, says Richard Alley, a glaciologist at Penn State. “It’s hard to predict how the ice will fracture,” he says. “That’s why you don’t want to tiptoe up on the disaster point. The edge between ‘it’s still there’ and ‘it’s had a catastrophic failure’ is something to be completely avoided.”

The other half of the Antarctic continent has shown more resistance to climate change, and hasn’t kept up with the global warming trend of the last few decades. That’s good news, since the East Antarctic Ice Sheet holds more water than its sibling — enough to raise sea levels by about 60 meters if it fails.

Last year, however, researchers using radar to penetrate the Antarctic ice announced that East Antarctica’s largest glacier, Totten Glacier, is still vulnerable. It may be at risk from encroaching ice-melting seawater. Radar maps revealed two seafloor troughs that could allow warm ocean water to melt the glacier’s underside, the researchers reported in Nature Geoscience. The glacier alone holds enough water to raise global sea levels by at least 3.3 meters, though its collapse could take centuries, the researchers noted.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse would raise global sea levels by as much as 3 meters

Expanding seawater and melting ice threaten the very existence of many island nations, including the Maldives. As climate change continues, rising sea levels could reshape Earth’s coastlines.KlemenR/iStockphoto

Sea Level Rise

2006: Melting ice and expanding seawater are raising global sea levels.

2016: Historical evidence suggests sea levels can rise more than 10 times as fast as they are now.

In the Indian Ocean, a city seems to rise out of the waves. The island of Malé, the capital of the Maldives and home to more than 150,000 people, sits just two or three meters above sea level (SN: 2/28/09, p. 24). The residents of Malé are a small portion of the approximately 200 million people worldwide living along coastlines within five meters of sea level. By the end of the century, as sea levels reach inland and coastal communities grow, the population at risk of rising waters may balloon to as high as 500 million.

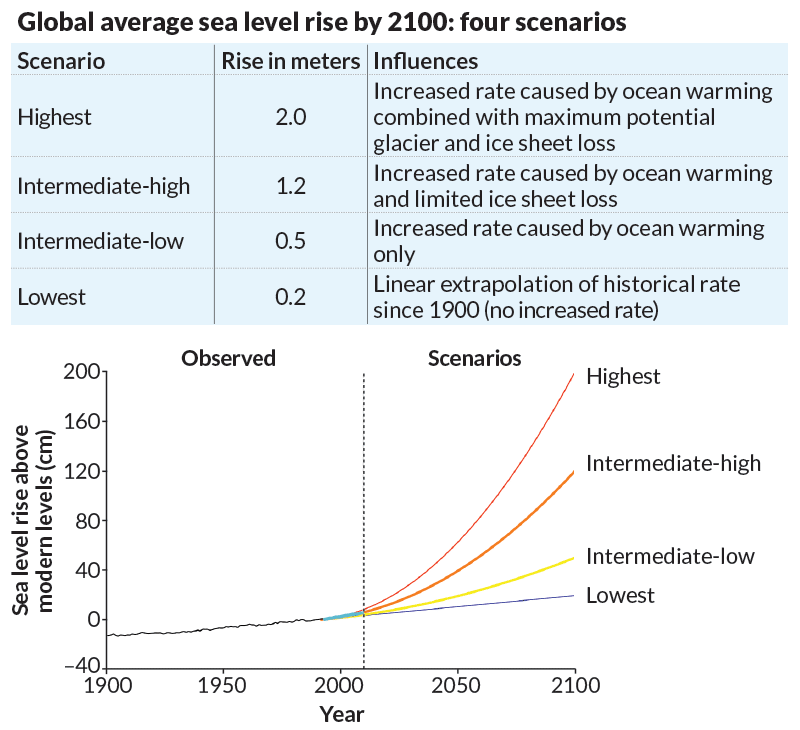

The global average sea level currently rises about three millimeters per year, with a meter of total sea level rise expected by 2100 if carbon emissions aren’t curtailed. Some areas, such as the U.S. East Coast, are experiencing even faster sea level rise. In February, researchers reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that 20th century sea level rise was faster than any other century since Rome was founded (SN: 4/2/16, p. 20).

RAISING THE STAKES Projections of future sea level rise vary, but scientists warn that even a small increase in sea level can worsen flooding and change coastlines. Sea level rise primarily stems from two sources: the thermal expansion of seawater and meltwater from land-based ice.Source: NOAA, Global Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States National Climate Assessment 2012

While sea levels are rising fast, they have the ability to climb even faster. Scientists are looking further into the future and investigating just how fast sea level rise could get, especially with a hypothetical collapse of the Antarctic ice sheets. Results gleaned from past warm periods suggest that sea levels can rise much faster than suggested just a few years ago — more than 10 times the present rate.

“Sea level is probably the biggest irreversible risk of global warming,” Columbia’s Raymo says. “I expect a hell of a lot more people are going to be personally impacted by a one-meter rise in sea level than by the extinction of the grand ladybug of something or other.”

Most records of ancient climates provide only a snapshot of how high sea levels have reached at a given time, not how quickly they moved up or down. But on a 2005 expedition to Tahiti, a research team caught a break. Because coral reefs require plenty of light to thrive, they typically take root in waters shallower than 10 meters deep. As sea levels rose in the past, corals moved higher up the newly submerged coastline. Off the coast of Tahiti, the researchers sampled fossils of ancient corals from the last 150,000 years buried in layers of ocean sediment. Dating the corals using the known decay rate of radioactive uranium into other elements, the researchers created an accurate, long-term sea level record.

Move slider at center to compare images

RISING TIDE A one-meter rise in sea levels would reshape many U.S. coastlines, including this section of North Carolina’s coast. Blue regions show areas submerged by water. Many scientists expect that sea levels will rise by a meter by 2100.Sea Level Rise and Coastal Flooding Impacts/NOAA

Around the end of Earth’s last glacial period, about 14,650 years ago, sea levels rose about 14 to 18 meters, the researchers reported in 2012 in Nature. What surprised those researchers is how quickly this rise happened: Sea levels rose at least 46 millimeters per year during that period. The scientists concluded that at least half of the 14 meters of sea level rise during this bout of warming originated from melting Antarctic ice.

“The scary thing, and this is why it’s kind of apocalyptic, is that once you start these things, they don’t stop,” Raymo says. “Everything we see shows that, if you look in the past, each increment of warmth seems to correlate with increasingly higher sea level.”

200

MILLION

Approximate number of people worldwide living along coastlines within five meters of sea level.

Scorching temperatures killed hundreds of people last year in Pakistan. Continued global warming will increase the risk of heat-related deaths, researchers warn.Shakil Adil/AP Photo

Extreme Temperatures

2006: Warming temperatures will cause more frequent and more deadly heat waves.

2016: Humidity may make future heat waves deadlier; cold snaps are on the decline.

Last summer, sweltering heat waves scorched India and Pakistan. The extreme temperatures killed thousands of people and were two of the deadliest heat waves since 1900. Such lethal heat will become more common as the planet continues warming, climate scientist Ethan Coffel of Columbia University said last December at the American Geophysical Union’s fall meeting.

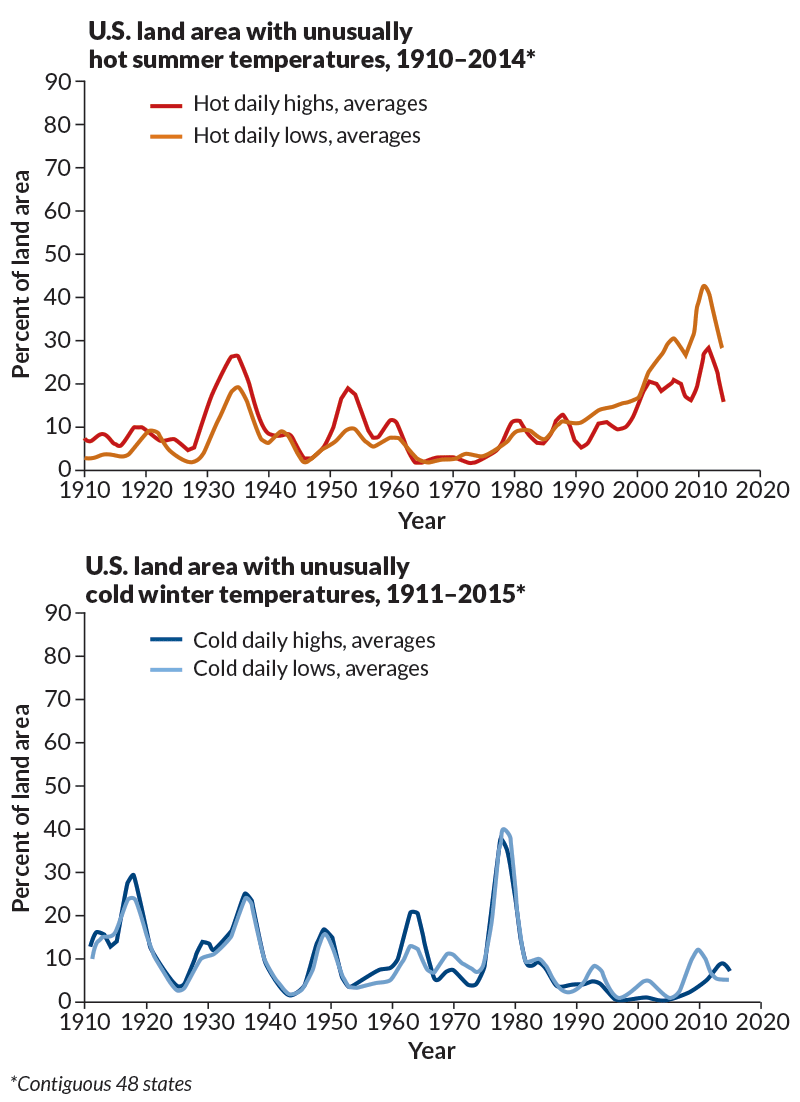

LESS EXTREME COLD Since the early 1900s in the United States, climate change has increased the frequency of abnormally hot summer days. But an expected rise in cold snaps has not played out. Areas hit by unusually cold temperatures in winter are declining.Source: NOAA 2015

The problem, Coffel said, is that climate change will raise humidity in many places alongside temperature as hot air wicks up more moisture. The evaporation of sweat keeps people cool when it’s hot, but high humidity can slow or even shut off this skin-cooling evaporation. Rising humidity will make rising temperatures more deadly than previously feared, he said. By the 2060s, Coffel predicts, 250 million people worldwide could face deadly levels of heat and humidity at least once a year.

While heat waves worsen, researchers say that another killer weather phenomenon will become less common. The frequency of abnormally cold periods in North America will decrease by roughly 20 percent by the 2030s, researchers reported last year (SN Online: 4/2/15). The work overturned previous projections of a rise in cold snaps over the coming decades as climate change redirects frigid Arctic winds. From 2006 through 2010, about twice as many people in the United States died from cold-related causes, such as hypothermia, than from excessive heat.

By the 2060s, Coffel predicts that 250 million people worldwide could face deadly levels of heat and humidity at least once a year.

China’s cities (Beijing’s Tiananmen Square shown) have suffered worsening air quality. Health risks posed by that pollution have motivated the country’s government to invest in low-emission alternatives to fossil fuels such as wind, solar and nuclear power.Spondylolithesis/iStockphoto

Climate Action

2006: The long-term effects of climate change deserve immediate action.

2016: Taking action comes with other, more immediate perks.

After decades of troubled negotiations and false starts, 195 nations from around the world gathered last December in Paris and agreed to take action on climate change (SN: 1/9/16, p. 6). The new commitment, to reverse the rise in greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial level, would have seemed impossible 10 years ago. Delegates will meet in a few years to decide whether to target a more ambitious limit of 1.5 degrees.

What’s changed is motivation, says Andrew Jones, a system dynamics modeler at Climate Interactive, a nonprofit organization in Washington, D.C., that works in partnership with MIT’s Sloan School of Management. Rather than focus on global climate benefits of curtailing fossil fuel emissions, which will take years to pan out, climate action is now increasingly driven by more immediate benefits, he says, such as improving public health. In February, researchers estimated that ambitious climate action in the United States would improve air quality enough to prevent 295,000 premature deaths by 2030 and save the economy hundreds of billions of dollars in medical costs.

Nearly 10 years after An Inconvenient Truth, 195 nations agreed to try to curb climate change. While Al Gore argued in the film that swift action was needed to prevent long-term problems, politicians are now increasingly motivated by immediate benefits.Patrick Kovarik/AFP/Getty Images

“Waiting for climate results is delayed gratification — it’s difficult to motivate continued action,” Jones says. “But if you reduce burning coal, air quality improves almost immediately.”

China, the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, backed the new climate deal after years of dragging its feet. The change of heart was chiefly driven by a desire to cut air pollution, not combat climate change, says MIT atmospheric scientist Kerry Emanuel. Earlier in December, smog-filled Beijing issued the country’s first pollution red alert and shut down the city until conditions improved.

Scouring recent climate change pledges, Jones and colleagues found that 60 percent of commitments, including those made by the United States, Mexico and South Korea, were explicitly motivated by short-term public health and economic benefits. Jones helps maintain C-ROADS, a climate simulator that forecasts the long-term outcome of climate action plans. Understanding and embracing the benefits of climate action will be essential to paving a path forward, Jones says, because C-ROADS has demonstrated that there are “hundreds” of ways to meet the 2-degree warming goal.

“We’ve moved from whether we’re going to do this to how we’re going to do this,” he says. “And that is very encouraging.”

Meeting the challenges posed by climate change will be hard, but Lonnie Thompson remains optimistic. “Three-and-a-half years ago I had a heart transplant,” he says. “At any other time in human history, this would have been thought of as impossible — my father died at age 41 of a heart attack. As human beings we’ve made tremendous progress on so many fronts. There will always be this resistance to change, but as a species, we’re capable of dealing with those changes.”

“Waiting for climate results is delayed gratification.... But if you reduce burning coal, air quality improves almost immediately.”