25 YEARS OF HUBBLE The Hubble Space Telescope, one of humankind's sharpest eyes to ever peer into the universe, continues to explore cosmological frontiers that were undreamt of when it launched 25 years ago.

NASA

- More than 2 years ago

On a chilly Saturday evening in March, unfazed by more than 6 inches of new snow, hundreds of people crowded into Shriver Hall at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore to hear the East Coast premiere of “Cosmic Dust,” an orchestral piece set to images of deep space. A trumpet fanfare conveyed the immense power of an exploding star; a cascade from the violins accompanied the flights of comets. As the symphony played, images of galaxies and nebulae scrolled by on a big screen.

Not many telescopes get a concert in their honor. But the Hubble Space Telescope is not just any telescope.

“Hubble is stargazing on steroids,” says Russell Steinberg, the Los Angeles-based composer who wrote “Cosmic Dust.” From its vantage point high above the blurring effects of Earth’s atmosphere, Hubble is one of the sharpest eyes ever to peer out at the universe.

Cosmic inspiration

Hubble’s iconic images inspired composer Russell Steinberg to write “Cosmic Dust,” a musical exploration of humankind’s connection to the cosmos. The Hopkins Symphony Orchestra performed the East Coast premiere on March 7 to an audience of stargazers and music lovers alike.

Credit: Russell Steinberg, composer; performed by the Hopkins Symphony Orchestra

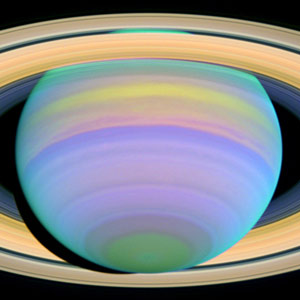

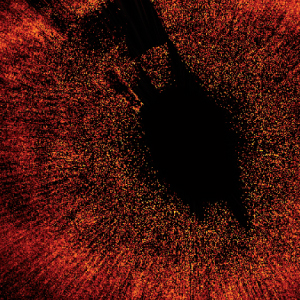

After 25 years in space, Hubble has seen it all. It witnessed fragments of a comet pummel Jupiter (SN: 7/23/94, p. 55). It spied planet nurseries silhouetted by the light of new stars in the Orion Nebula. It confirmed that in the center of every large galaxy lurks a supermassive black hole, an invisible behemoth weighing up to several billion suns. Hubble even monitored pulsating stars as far as 70 million light-years away. By doing so, it resolved a decades-long dispute about the expansion rate and age of the universe (SN: 4/5/14, p. 18).

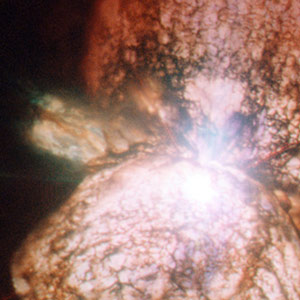

And, of course, there are the pictures. From the Pillars of Creation, where newborn stars sculpt spires of gas several light-years high, to the Hubble Deep Fields, where more than 10,000 galaxies span vast expanses of space and time, Hubble’s iconic images set a new standard for how astronomers — and the public — see the universe.

Not too shabby for a telescope that started off as the butt of late-night TV jokes after its misshapen mirror sent home blurry early images.

Hubble has been such a “spectacular success,” says University of Chicago astronomer Wendy Freedman, “because it was just a huge step beyond what we were capable of doing before.”

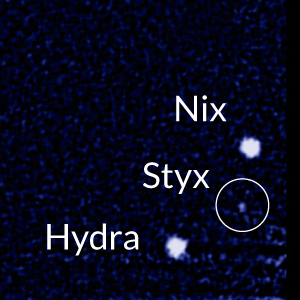

Today, Hubble is exploring frontiers that were unimagined when the telescope rode the space shuttle Discovery into orbit on April 24, 1990. “The vast majority of what we’re looking at now wasn’t even dreamt of,” says Howard Bond, an astronomer at Penn State. No one knew that the expansion of the universe was accelerating. Other solar systems existed only in people’s imaginations. And, of course, Pluto was still a planet.

“We didn’t have enough imagination at the beginning to think of all the things that nature does,” says Robert Kirshner, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. A diverse package of cameras and spectrometers combined with the ingenuity of the telescope’s operators, he says, let Hubble try things that no one planned for.

Hubble’s longevity owes a tremendous debt to human spaceflight. Astronauts have returned five times — including a 1993 trip to install corrective optics for the flawed mirror. Each visit brought spare parts and more advanced instruments.

“The telescope right now at age 25 is working better than it has at any time in the past,” Kirshner says. The images are sharper and reach farther than before. Barring a catastrophic failure, Hubble will probably celebrate a 30th anniversary as well.

With an infrared camera added during the last servicing mission in 2009 (SN Online: 5/26/09), Kirshner is trying to solve one of astronomy’s thorniest mysteries: Why is the expansion of the universe speeding up? He’s using Hubble’s new infrared eye to observe a class of supernovas called type 1a in other galaxies. These exploding stars are useful distance markers because they emit roughly the same amount of light. Such supernovas more consistently reach the same brightness in infrared light than they do in visible light, so Kirshner hopes the infrared camera will give a more precise look at how cosmic expansion has changed through time.

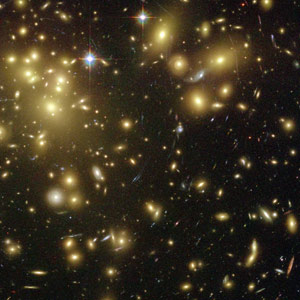

Astronomers are also pointing the new camera at galaxies near the far reaches of the visible universe to look back in time. The light has taken more than 13 billion years to reach Earth, so the galaxies appear as they did just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. The expansion of the universe in that time has stretched the visible light from these galaxies to infrared wavelengths that Hubble’s new camera can detect (SN: 1/30/10, p. 5).

Piecing together Hubble observations with those from other telescopes, astronomers can see how galaxies have evolved throughout cosmic history. Galaxies start as oddly shaped clumps of gas and stars that repeatedly merge over the age of the universe, eventually building the large spiral and elliptical galaxies we see today.

“We know the universe formed stars furiously when it started, then reached a peak some 10 billion years ago, and it’s been declining ever since,” says Mario Livio, an astrophysicist at Hubble’s headquarters, the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. “Nobody knew that was something that would come out of Hubble.”

Neither did anyone know that Hubble would be sniffing around in the atmospheres of planets that orbited other stars. “People would have thought you were crazy if you’d even mentioned that,” Bond says.

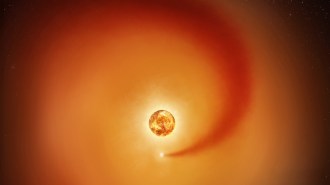

Astronomers discovered the first planets outside the solar system two years after Hubble launched. In 2000, Hubble saw the first hints of an atmosphere around an exoplanet (SN: 12/1/01, p. 340). As the planet crossed in front of its star, certain wavelengths of starlight were blocked by gas in the planet’s atmosphere. Since then, Hubble, along with other telescopes in space and on the ground, has tallied the chemical makeup of more than 50 worlds. “Hubble is right now the preeminent facility with which we can make those measurements,” says Caltech astronomer Heather Knutson.

Knutson is using Hubble to understand the origin of super-Earths, planets that are a few times as massive as Earth (see “Super-Earths may form in two ways“). Astronomers don’t understand how these heavyweights form. But the atmospheres might keep a record of where they formed, which is a first step to figuring out how.

Researchers aren’t the only ones who have fallen under Hubble’s spell. When the public thinks of astronomy, Knutson adds, Hubble’s images are one of the first things that come to mind. “Hubble has shaped our view of what astronomy is,” she says.

NASA has gone to great lengths to make Hubble’s images easily accessible to the public, says Jennifer Wiseman, an astrophysicist at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. The artistry of the iconic pictures owes a lot to the Hubble Heritage Project, founded by Bond and others in 1998 (see “The art of astronomy“). Aside from showing the taxpayers what they paid for, Wiseman sees a much loftier outcome.

“It’s helped people around the world feel a sense of unity,” she says. “We’re all brothers and sisters on this one planet that’s part of an incredible larger universe.”

Given the public’s response to Hubble, that philosophy seems to resonate. The images have inspired poetry, dance and, of course, music.

After the March concert, Steinberg seems almost giddy as he shakes hands with Hubble astronomers and former astronaut John Grunsfeld, who visited Hubble three times.

For Steinberg, the music is his way of helping people grapple with the immensity of what Hubble has revealed during its 25 years and to connect it to ourselves. The reason we yearn to look at the heavens, he says, is that we’re seeking our origins. “That curiosity we have to look at the sky,” he says, “is so primal to what makes us human beings.”