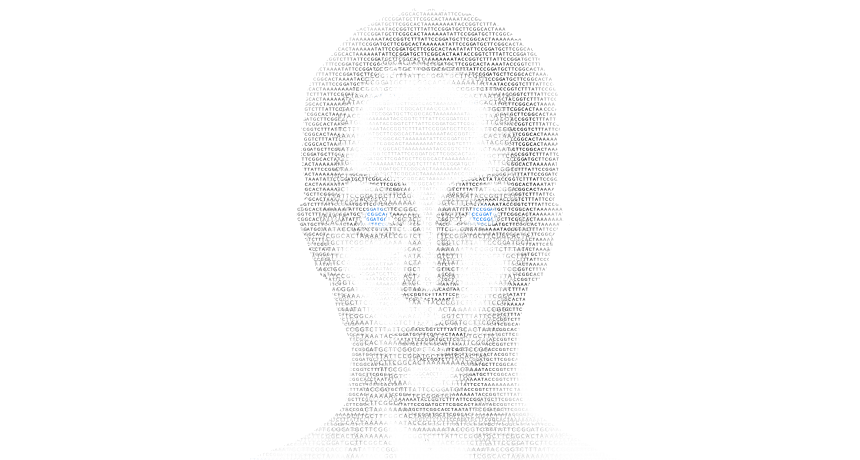

Can DNA predict a face?

Though appearance-prediction technology shows promise, it’s still in its infancy

MUG SHOT DNA-based facial sketches are moving into the crime-solving arena.

E. Otwell

Florida police are searching for a man who lurks in the shadows.

For more than two years, he has terrorized at least a dozen women, peeping into windows and slipping into bedrooms to watch them sleep.