NASA’s Europa mission is a homecoming for one planetary astronomer

Bonnie Buratti will search for signs of habitability on Jupiter’s icy moon

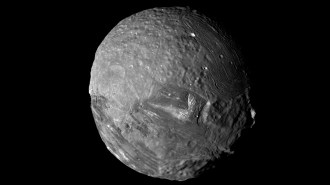

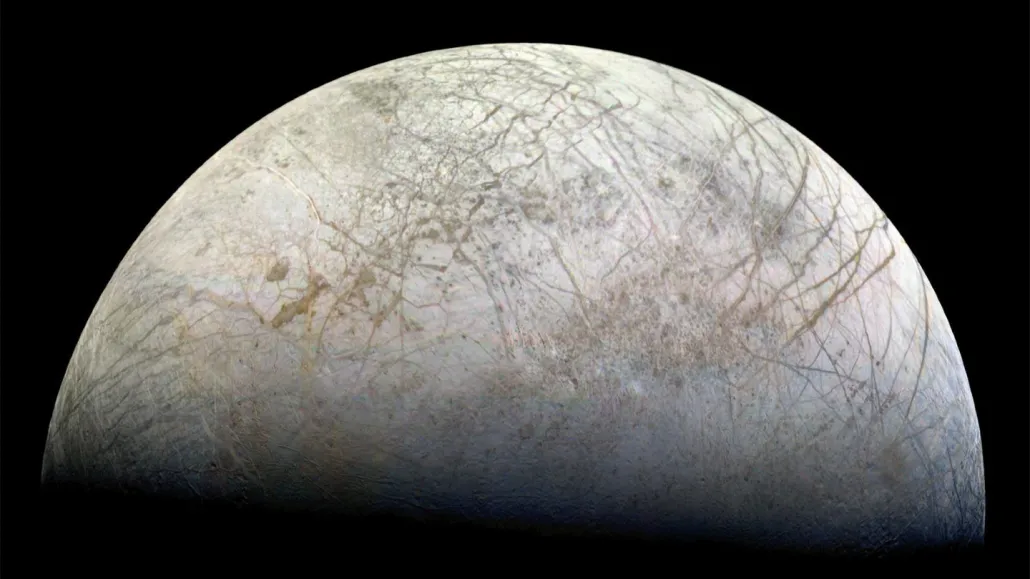

In its first spacecraft portraits, Jupiter’s moon Europa (seen here in a 1979 photo from Voyager 2, reprocessed in 2010) looked like a cracked egg. Now, a new spacecraft is going to get a better view of what’s under its shell.

JPL/NASA, Ted Stryk (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Planetary astronomer Bonnie Buratti remembers exactly where she was the first time she heard that Jupiter’s icy moon Europa might host life.

It was the 1980s, and Buratti was a graduate student at Cornell University studying images of the planet’s moons taken during the Voyager 1 and 2 flybys in 1979. Even in those first low-resolution snapshots, Europa was intriguing.

“It looked like a cracked egg,” she says.

Those cracks — in a snow-covered, icy shell — were probably filled with material that had welled up from below, Buratti and colleagues had shown. That meant there had to be something underneath the ice.

Buratti recalls fellow grad student Steven Squyres giving a talk about the possibility that Europa’s ice hid a salty liquid ocean. “He said, ‘Well, there’s an ocean underneath, and where there’s water, there’s life,’” she recalls. “And people laughed at him.”

They’re not laughing anymore.

Over the past four decades, Buratti has seen the search for life in the solar system go from a joke to a flagship mission. She is now a deputy project scientist for NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which launched October 14 to find out if Europa is in fact a habitable world (SN: 10/8/24).

“I’m kind of coming home,” she says.

Space science first captured Buratti’s imagination in childhood, which coincided with the beginning of the space age. She was a child when the Soviet Untion launched Sputnik and a teenager when Apollo 11 landed on the moon.

“I got a telescope when I was in third grade,” she says. She remembers figuring out the constellations from her front lawn in Bethlehem, Pa. “From an early age, I was always curious.”

Planetary science drew her in with the field’s larger-than-life personalities. In graduate school, she worked with science celebrities including Frank Drake and Carl Sagan, who were spearheading efforts to take the search for extraterrestrial life seriously (SN: 11/1/09; SN: 11/7/14). That gave her a sense that the universe could be teeming with life, but not the support she needed to get through her Ph.D. She ended up working with less famous but equally charismatic astronomer Joe Veverka. It was Veverka who gave her the Voyager images.

Buratti joined NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, Calif., in 1985 and has been there ever since. But while the Galileo spacecraft was finding evidence of Europa’s subsurface ocean in the 1990s, Buratti was busy exploring Saturn with the Cassini mission (SN: 2/18/02).

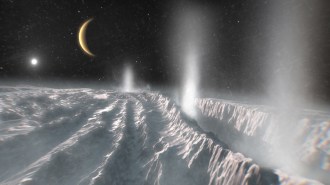

Saturn’s moons were full of surprises, including phantom hydrocarbon lakes on Titan, watery plumes from Enceladus and a mysterious ridge that makes Iapetus look like a walnut (SN: 4/15/19; SN: 8/4/14; SN: 4/21/14). “It was just one thing after another,” Buratti says.

Those discoveries helped advance the notion that subsurface oceans in the solar system might not be so strange after all. Hints of oceans have since turned up as far away from the sun as Pluto, Buratti’s favorite planet — and yes, she still calls it a planet (SN: 3/27/20). There may be ocean worlds orbiting other stars, too.

So when Europa Clipper arrives at Jupiter in 2030, scientists are looking to this moon as an example of worlds that may be common in the universe. Clipper will orbit Jupiter and make at least 49 flybys of Europa, to limit the amount of time the spacecraft spends in Jupiter’s punishing radiation belts. It will take measurements of the moon’s surface composition, gravity and internal structure to assess how suitable the small world is for life.

Buratti joined the Clipper mission in 2022, as one of the people in charge of making sure the team squeezes as much science out of the mission as they can. “We have always felt that our role is to enhance science, to get the very best science out of the mission,” she says. She and the scientific community at large are confident that they’ll find something good.

“We’re pretty certain there’s a habitable environment,” she says. Echoing that graduate school talk from decades ago, she adds: “On Earth, wherever you see water, you see life. So, I think it’s a really good place to look.”