With nowhere to hide from rising seas, Boston prepares for a wetter future

The coastal city is taking the hint from recent storms and floods

ON THE RISE Bostonians are getting used to flooding. Morrissey Boulevard (shown), near the campus of University of Massachusetts Boston, gets hit several times a year during high tides.

David L. Ryan/Boston Globe/Getty Images

Boston dodged a disaster in 2012. After Hurricane Sandy devastated parts of New Jersey and New York, the superstorm hit Boston near low tide, causing minimal damage. If Sandy had arrived four hours earlier, many Bostonians would have been ankle to hip deep in seawater.

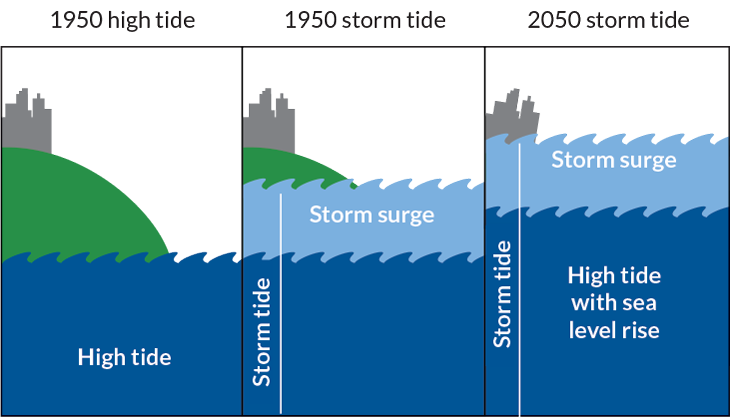

Across the globe, sea levels are rising, delivering bigger storm surges and higher tides to coastal cities. In Boston, the most persistent reminder comes in the form of regular “nuisance” flooding — when seawater spills onto roads and sidewalks during high tides. Those nuisance events are harbingers of a wetter future, when extreme high tides are predicted to become a daily occurrence.

“The East Coast has been riding a post-Sandy mentality of preparing and responding before the next big one,” says Robert Freudenberg, an environmental planner at the Regional Plan Association, an urban research and advocacy firm based in New York City. But a more enduring kind of threat looms. “Sea level rise is the flooding that doesn’t go away,” he says. “Not that far in the future, some of our most developed places may be permanently inundated.”

And Boston, for one, is not waiting to get disastrously wet to act. In the seven years since Hurricane Sandy’s close call, the city-run Climate Ready Boston initiative has devised a comprehensive, science-driven master plan to protect infrastructure, property and people from the increasingly inevitable future of storm surges and rising seas. The famously feisty city intends to be ready for the next Sandy as well as the nuisance tides that promise to become the new normal, while other U.S. coastal cities are trying to keep up.

Water always wins

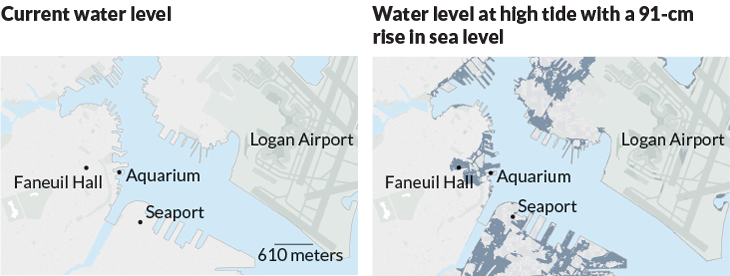

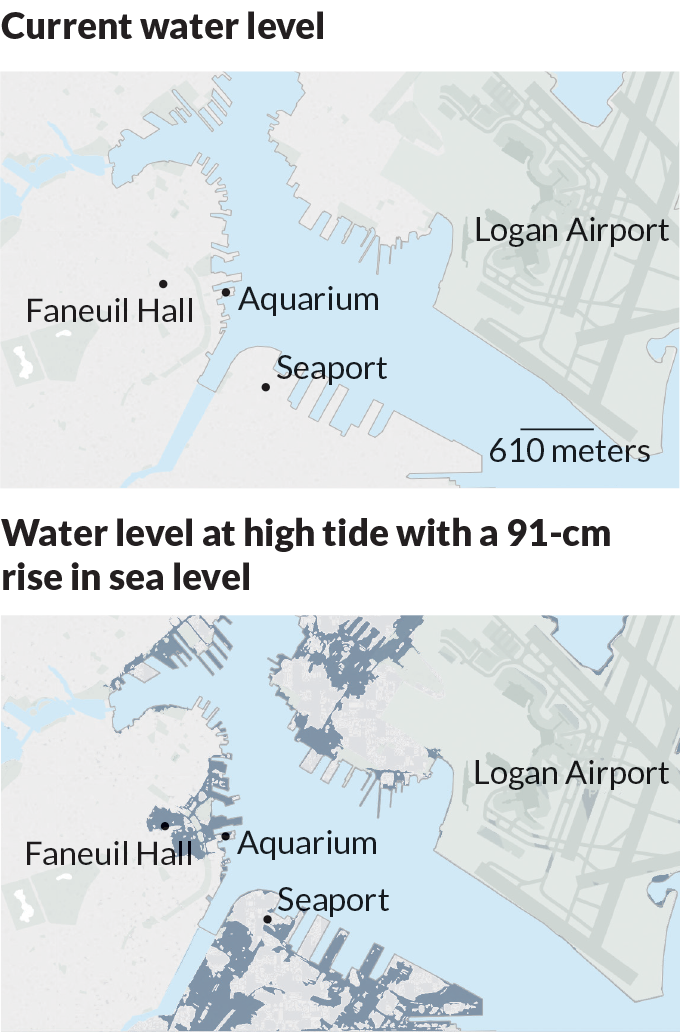

British colonists founded Boston in 1630 next to a freshwater spring on the heavily forested Shawmut Peninsula. By the 1800s, the trees had been replaced by a bustling trading port. As the population grew, industrious residents began filling in tidal flats and marshland with rocks, dirt and trash to create more buildable space. By the early 1900s, the city had tripled in geographic land area. The South End, Charlestown, East Boston, Back Bay and downtown neighborhoods, including attractions like historic Faneuil Hall and the New England Aquarium, are all built on landfill. Even Logan International Airport is built atop a filled-in tidal flat that was once five islands.

Of course, early Bostonians had no idea that rising seas would one day threaten former lowlands. With more filled-in land area than most major U.S. cities and 75 kilometers of shoreline, Boston is the fifth most vulnerable coastal city to flooding from sea level rise in the United States — after Miami, New York City, New Orleans and Tampa — and the eighth most vulnerable city in the world, in terms of overall cost of potential damage, according to the World Bank.

When it comes to coastal flooding, Boston has a lot stacked against it. The city’s official elevation is 14 meters above sea level, but its lowest areas sit at sea level.

Over the last century, sea level in Boston Harbor rose by about 28 centimeters, due to both thermal expansion of seawater as the oceans warm (SN Online: 9/28/18) and the melting of distant ice sheets. Conservative projections for Boston place sea level about 15 centimeters higher by 2030, 33 centimeters higher by 2050 and 149 centimeters higher by 2100. In a worst-case scenario, if greenhouse gas emissions continue at the current pace, sea level could rise by as much as three meters by 2100.

New England and the eastern shore of Canada have a unique combination of geographic factors that push water farther inland in response to high tides: The region’s shallow seafloor topography tends to funnel water higher inland, and its proximity to the Gulf Stream — a major ocean current that runs from the Gulf of Mexico up along the East Coast — also helps magnify tides. Due to rising ocean temperatures, the Gulf Stream is slowing down, causing even more water to pile up along the East Coast and boosting high tides, physical oceanographer Tal Ezer of Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va., reported in June in Earth’s Future.

In 2017, Boston racked up a record 22 nuisance tides (defined in Boston as tides over 3.8 meters above average sea level), according to a 2018 report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. As sea level creeps higher, the Seaport and some other areas of Boston could see daily tidal flooding by mid-century, says Kirk Bosma, a coastal engineer with the Woods Hole Group in Massachusetts.

Flooding during extreme high tides, when there’s no storm in sight, already happens in East Boston, Charlestown and the downtown waterfront (SN Online: 7/15/19). David Cash, an environmental policy expert at the University of Massachusetts Boston, has witnessed high tide flooding from his office overlooking Dorchester Bay and Morrissey Boulevard, a major thoroughfare and the primary road to the campus. “Morrissey Boulevard now floods several times a year at high tide on blue sky days,” Cash says.

If a storm hits at high tide, its effects can be greatly magnified, creating a storm tide, Bosma says. Boston lies in the path of both winter nor’easters and Atlantic hurricanes, which are increasing in intensity, NOAA reported in July in an overview of current research on global warming and hurricanes. When storm surges and heavy rain or snow hit coastal cities with more concrete than absorptive marshland, the combination can overwhelm urban drainage systems and cause flooding.

The winter of 2018 was stormy, even by New England standards. In January, winter storm Grayson dumped more than 40 centimeters of snow on Boston. Streets were flooded deep enough to float large dumpsters in the dark, icy water.

“During the storm, the high tide came right up over the seawall, across the street and poured into my office building’s parking garage,” says Joel Carpenter, an equity trader at Congress Asset Management in the Seaport. As massive plow trucks drove through about a meter of seawater, pushing huge ice chunks out of the way, Carpenter wondered how he would get home. “Public transport was shut down.” He had to walk through ankle-deep water to a spot several blocks from his office, where an Uber was willing to pick him up.

When the ocean surged 4.6 meters above the high tide mark, Grayson broke the record set in 1978 for the highest storm tide. Just two months later, in March, winter storm Riley delivered another record storm surge. Like it did in 2012, the city got lucky: Riley didn’t hit at high tide, Bosma says. “If Riley had occurred with hide tide, it would have been disastrous.”

As it was, public transportation ground to a halt and the National Guard had to come in to help evacuate stranded motorists and residents. “These storm events are a real wake-up call,” Cash says. “Our future is going to be wet.”

Heads together

By the time those winter storms hit, Boston was already getting serious about protecting itself against flooding. In 2015, officials assembled BRAG, the Boston Research Advisory Group, to bring Boston-based researchers together to guide science-based decision-making for Climate Ready Boston.

“BRAG is like a mini Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change just for Boston,” says BRAG member Ellen Douglas, a hydrologist at the University of Massachusetts Boston. BRAG combines peer-reviewed literature and locally sourced published data to project Boston-specific impacts of heat waves, storms and sea level rise.

In 2016, BRAG released its first report, “Climate Change and Sea Level Rise Projections for Boston.” The references run long, citing more than 100 studies.

Based on the probabilities of the various sea level rise scenarios outlined in the report, Boston is preparing for up to 100 centimeters of sea level rise. Future zoning and coastal resilience projects — those intended to protect people and keep property from flooding — will need to safeguard against at least 100 centimeters, about a yardstick’s worth, of sea level rise.

“We did a full citywide vulnerability assessment [of] how, when and where the city would be affected over different time frames,” using BRAG’s sea level rise estimates, says Bud Ris, a senior member of the Green Ribbon Commission, a consortium of business, institutional and civic leaders that advises Climate Ready Boston.

Boston is ranked eighth worldwide for expected economic losses due to coastal flooding, estimated at $237 million per year in 2005 and $741 million annually by 2050, according to a 2013 study in Nature Climate Change. “Those kind of numbers frame the upfront costs and the call to action pretty starkly,” Ris says. “If we don’t do the work now, we are going to pay even more later.”

The cost of adaptation is daunting; estimates range into the billions of dollars over the next 50 years. In April, Boston Mayor Martin Walsh pledged 10 percent of the city’s $3.49 billion capital budget in 2020 to fund resiliency projects, such as raising major roadways and replacing existing concrete structures and pavement along coastlines with floodable green spaces.

Though much more money will be needed, Massachusetts has a history of coming up with funds for staggeringly expensive public works projects, Ris says. Cleaning up the infamously filthy Boston Harbor cost taxpayers about $5 billion over two decades. The city spent $22 billion on the Big Dig, the country’s most expensive highway project that took two decades to reroute the city’s formerly elevated Central Artery into a tunnel system completed in 2007. “If we come up with a workable plan, the money will come from somewhere,” Ris predicts.

Blue Boston

One of the first steps toward building a more flood-resilient Boston was to map where the water will go, Douglas says.

“The first set of maps we put out [in 2011] showed what the coastline of Boston will look like by the year 2100 with sea level rise and a large storm surge. The map got a lot of attention because it was so blue.”

With 100 centimeters of sea level rise, much of Boston’s fill land will be inundated by the harbor, returning the remaining landmass to the original shape of the Shawmut Peninsula. Low-lying city landmarks such as North Station, Faneuil Hall and the aquarium would be permanently awash in blue.

The Boston Harbor Flood Risk model, released in 2015, shows how flooding in and around Boston Harbor will change over time under various scenarios.

“We looked at thousands of different [historical and simulated] storm events combined with sea level rise, waves and tides, and determined the movement of floodwaters out of the harbor and into the streets,” says Bosma, who led the modeling project. The model identified the financial district, Fort Point Channel and the Blackstone Block Historic District as among the city’s most vulnerable areas.

“If you just look at the 2100 maps, [preparing for flooding] can seem pretty hopeless,” Bosma admits. “But the models show where we need to focus our money and efforts right now and where we can plan for future projects in 2030, 2050 and beyond.”

The city government has also been working on making more detailed street-by-street maps of Boston’s many neighborhoods, says Carl Spector, Boston’s commissioner of the Environment Department.

“We started with East Boston and Charlestown, because they are already seeing flooding,” he says. That report was released in 2017, followed by a report for South Boston in 2018. The city is now evaluating the downtown and North End districts. “These reports have priority lists and recommended timelines for when projects should be started and completed over the next 30 years,” Spector says.

Concrete vs. green space

Protecting individual buildings from flooding usually involves waterproofing lower floors, raising electrical equipment and installing pumps to remove floodwater. But on a citywide scale, flood protection starts at the coastline. The most efficient way to prioritize resiliency projects is by focusing on efforts that can protect entire neighborhoods, rather than single buildings, Bosma says. “Boston is not flat; it actually has quite a bit of topography that directs water in certain ways. We look to the coast and try to come up with more regional solutions — whether that be a floodwall or a berm or a park — that can protect a whole slew of inland assets all at once.”

So why not build a concrete seawall around Boston Harbor to protect the entire city? BRAG and the Sustainable Solutions Lab at the University of Massachusetts analyzed the feasibility of installing a pair of barriers across the harbor. “It doesn’t make a lot of sense from both financial and operational standpoints,” Bosma says. A permanent barrier would cost as much as $20 billion and require intensive maintenance. Plus it could limit the size and frequency of ships coming and going from the harbor as well as impede the flow of water needed to maintain water quality.

Building a dynamic harbor barrier, with gates that open and close to allow for shipping and water flow, is feasible from an engineering standpoint, Bosma says. But by 2040 or 2050, sea level will probably be high enough that such gates would need to be closed for almost every high tide to prevent flooding. “The size and magnitude of the gates required would take six to eight hours to open or close,” he says. “They’d have to be almost constantly moving.”

Shore-based solutions that buffer against high tides and storm surges make more sense, the analysis found. Nature-based coastal adaptations such as parks and wetlands that can absorb the flooding are not only effective but also bring added benefits such as native habitat restoration, tourism and recreational opportunities, according to a study conducted on the Gulf Coast and published in 2018 in PLOS ONE.

“As much as possible, we’re using nature-based solutions that are flexible and can be adjusted over time to conditions depending on what happens with sea level rise,” Bosma says.

Infrastructure’s tangled web

Resilience is about more than keeping buildings dry. “We may be able to protect Boston’s buildings, but if people can’t turn on the lights and can’t flush the toilets and they can’t get to work via public transportation and they can’t call for help because the phones don’t work, we’re going to be in deep trouble,” says John Cleveland, executive director of the Green Ribbon Commission.

Outages in the power grid, as well as telecommunications, water and gas services — which rely on the power grid — can cascade inland to places that never actually get wet, says Rae Zimmerman, an urban infrastructure planner at New York University.

For convenience, fiber optics, gas mains, water mains and electric power distribution lines often share the same underground conduits. “It’s cheaper to install and maintain them that way, but it also means that when one system goes haywire, they all go,” Zimmerman says.

Climate Ready Boston is behind in this arena. “As far as I know, the city hasn’t started coordinating its strategy around its infrastructure for transportation, energy, water, wastewater and communications,” Bosma says. “We need to be embedding resilient design standards into ongoing infrastructure investments.”

For example, when the city overhauled its stormwater and wastewater sewer systems 30 years ago, “we didn’t foresee the problem of sea level rise,” says John Sullivan, chief engineer of the Boston Water and Sewer Commission. During flood events, partially shared wastewater and stormwater drainage systems make keeping seawater out of Boston’s wastewater treatment plants a challenge.

The city is now researching strategies for storing influxes of stormwater using existing natural depressions in the landscape and even parking garages, so that saltwater does not get into the wastewater treatment plants and wreak havoc on the microbes that help process the waste. One goal is to incorporate backup systems that flow with gravity and don’t require pumping. “If we can avoid having to pump, which requires electricity, we’ll be better off in the event of a power outage,” Sullivan says.

Last summer, a team led by computer scientist Paul Barford of the University of Wisconsin–Madison released a series of maps that overlapped the physical internet — fiber-optic cables, hubs and data centers — with projections of sea level rise in major U.S. coastal cities. Just like with the water systems, nobody was thinking seriously about sea level rise when the infrastructure that runs with the internet was installed 20 years ago, Barford says. “Now we have thousands of miles of cables and major data centers that are susceptible to damage during coastal flooding events.” Waterproofing vulnerable components of the physical internet may help, but the most critical infrastructure may need to be moved inland away from the coasts, he says.

Pipes, conduits and power lines follow existing roadways, so some utilities may be able to piggyback on the maps and strategies developed for the Massachusetts Department of Transportation and the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, Douglas says.

“MassDOT has taken all of our reports very seriously,” she says. “They have a lot of infrastructure in the way of sea level rise.” Perhaps the biggest challenge is to keep the Big Dig highways open for traffic while protecting the tunnels from flooding, Douglas says. “You can’t just close off the tunnels. They are important evacuation routes during emergencies, but they were not built to tolerate any amount of flooding.”

Resiliency projects

Not so long ago, sea level rise was considered a distant problem, something to deal with a hundred years or more from now. But sea level rise is already lapping at U.S. shores. Boston may be among the oldest cities in the country, but it also might prove to be one of the most resilient.

The Climate Ready Boston plan is well under way, with completed district-level projects in East Boston, Charlestown and South Boston. Work includes installing a deployable floodwall along the East Boston Greenway, elevating a section of Main Street in Charlestown to protect a large swath of the neighborhood and removing concrete to restore floodable parks and green space in South Boston and the Seaport.

With momentum building in Boston, the resiliency project is expanding to the rest of the state; Massachusetts has over 300 kilometers of coastline to protect, including the curled arm of Cape Cod. This spring, Massachusetts Speaker of the House Robert DeLeo and Governor Charlie Baker each pledged $1 billion in grants for resilient infrastructure and climate adaptation projects across the state.

When it comes to implementing climate adaptation strategies, other cities, including New York, can learn from Boston, says Freudenberg, the environmental planner in New York. “Developing a vision for climate adaptation is easy. Implementing that vision is much harder,” he says. “At some point, once we’ve considered the science and all the available strategies, we have to start building. It’s been seven years since Sandy and seas are rising. It’s time to take action.”