Bones reveal what it was like to grow up dodo

Cutting into precious bone specimens gives clues to the extinct birds’ life and times

SUMMER OF DANGER Mother and chick dodos, illustrated here, needed to eat well and get healthy before the stressful cyclone season, according to a new reconstruction of the extinct bird’s life.

Julian Hume

Dumb extinction jokes aside, dodos’ life history is largely unknown.

Now the first closeup look inside the long-gone birds’ bones is giving a glimpse into their lives, an international research team reports August 24 in Scientific Reports. Until now, almost nothing has been known about the basic biology of dodos, such as when they mated or how quickly they grew.

Based on 22 bones from different birds and weather patterns on the island Mauritius where the birds lived, scientists worked out how bones change as birds grew up. With this information, the team proposes a month-by-month dodo to-do list. For August: Start breeding. That’s the end of winter in the Southern Hemisphere, where Mauritius lies. Chicks would hatch in spring and grow in a rapid spurt before summer, proposes study coauthor Delphine Angst, a paleontologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

Summer would have been the toughest season for dodos, the team says. Between about November and March, cyclones can rip across the island, uprooting plants, stripping leaves and fruit and disrupting food sources. During that time, the birds probably just about stopped growing, a lag that could explain periodic lines in bones where birds had deposited little new material.

On top of those lag lines, some bones also show relatively little new growth before signs of molting. This pattern suggests that as summer was winding down in March, adults that had survived cyclone season started renewing their feathers. The fine new plumage should thus be ready in time for August flirtations.

Story continues after graphic

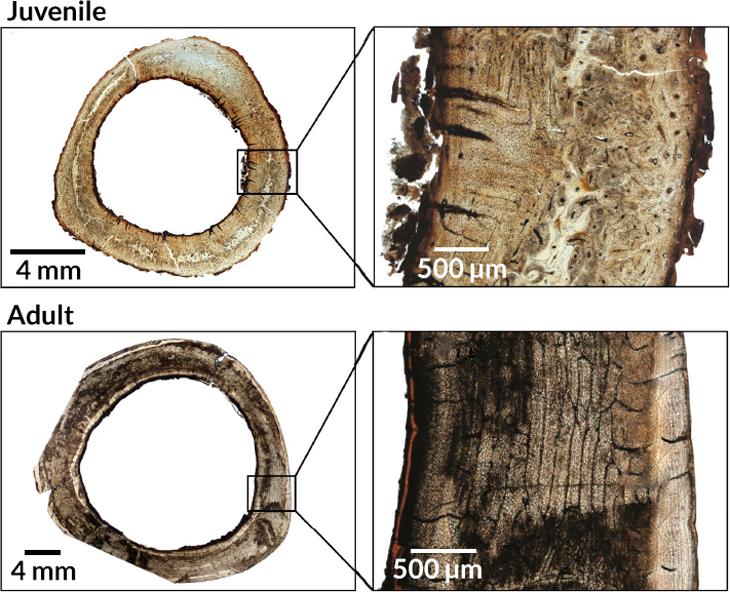

Young and old

These cross sections of leg bones were used to help to distinguish between young and mature dodos. The juvenile (top row) had a thick zone of rapidly formed bone with irregular patterning on the outside wall, plus a more slowly deposited, more orderly looking layer on the inside wall. A sexually mature adult (bottom row) shows a slowly deposited, more orderly zone on the outside wall.

The dodo, Raphus cucullatus, lived only on the island of Mauritius in the southwestern Indian Ocean. The bird slid from a marvel first described to Westerners in 1598 to extinction in less than a century, Angst says. Sailors delirious for fresh meat slaughtered flocks, but more destructive, she thinks, were the rats, pigs, monkeys and other invaders that sailors left behind.

Museums have few dodo bones, and the new study was only possible because of recent discoveries of new specimens that let scientists feel more comfortable about actually cutting sections out of some of the precious collections. The Dodo Research Program turned up more bones in Mauritius. And Angst herself got a startling message from people selling a house near Paris that was once owned by a 19th century naturalist born on Mauritius. “We have lot of dirty old stuff in the corner of the house — are you interested?” she remembers being told. “It was literally the morning before Christmas,” she says, when she discovered a treasure trove of long-forgotten dodo bones.

Various kinds of microscope views let the researchers identify an almost grown-up youngster. It had built bone with collagen fibers and other materials in disorderly patterns typical of fast chick growth among many modern birds.

In bones identified as coming from mature dodos, that disorder had turned into more orderly layers. Though dodos were flightless, they grew like most modern birds, which can fly, researchers concluded. Some other flightless birds, such as ostriches, grow their skeletons fast but then stop abruptly with no restructuring, Angst says.

The dodo bones also revealed markers of other life events. Some had inner gaps like those created when modern birds pull calcium out of their bones to make new feathers in a hurry during the annual molt. Two of the bones showed an extra calcium buildup on the inner hollow core. That suggests that these bones belonged to ovulating females storing calcium to form eggshells.

While the proposed dodo calendar is speculative, the assumptions “are not unreasonable,” says paleontologist William Sellers of University of Manchester in England, who was not part of the new study. The proposal could explain records from sailors who noted different looks for dodo plumage at different times of year.

The proposed timing of life events also makes sense based on what’s known about birds now living on Mauritius, says Antoine Louchart. The bird paleontologist, of the French national research institute CNRS at École Normale Supérieure de Lyon, was not part of the new research. The bones do help flesh out the dodos’ tale, Louchart says. Modern birds can only provide some hints of the life and times of dodos, he says, “because the dodo was so modified and so unique in its proportions, size and flightlessness.”