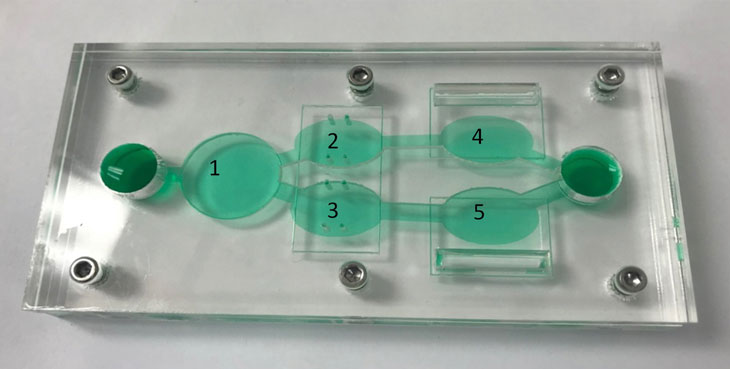

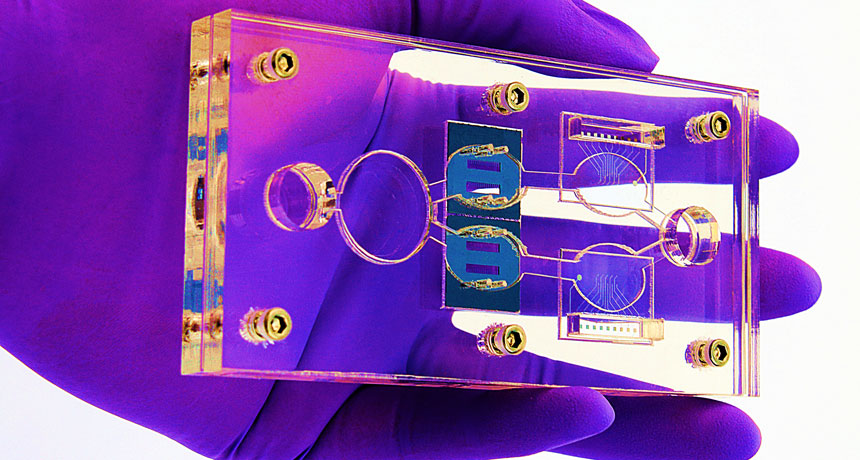

This body-on-a-chip mimics how organs and cancer cells react to drugs

Five chambers house different tissues, connected by channels that help simulate blood flow

BIOLOGICAL MICROCOSM A new body-on-a-chip device can hold several different types of human cells and could help scientists quickly and accurately test the intended and unintended effects of drugs.

Hesperos