‘Blastoids’ made of stem cells offer a new way to study fertility

Models of early-stage embryos could be used to research contraceptives too

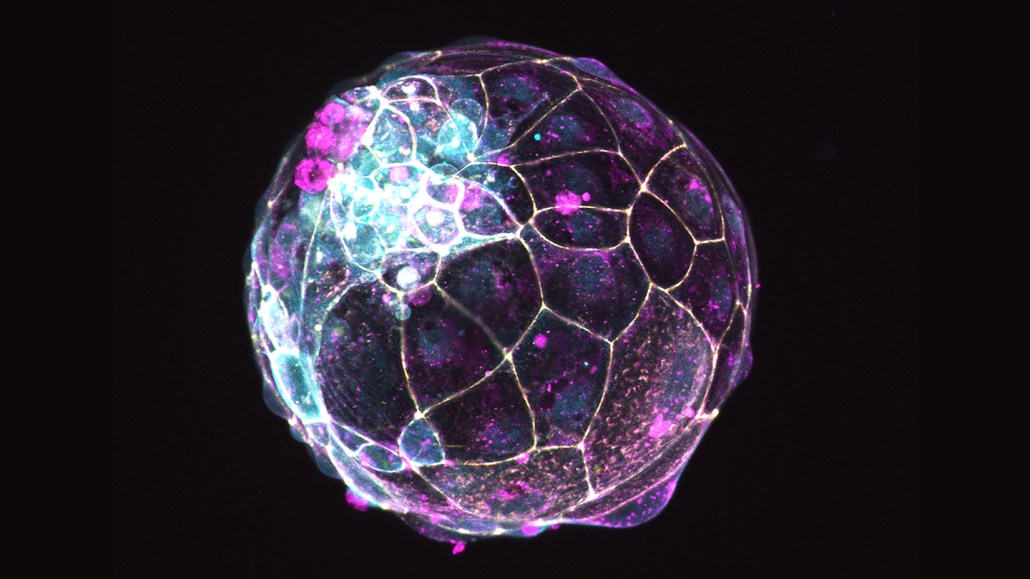

Human stem cells can be used to create models called blastoids (one shown that has been chemically altered to fluoresce) for studying how early-stage embryos implant into the lining of the uterus.

© N. Rivron/IMBA, Nature