A biochemist’s extraction of data from honey honors her beekeeper father

The tests could be used to figure out what bees are pollinating and which pathogens they carry

Honey is full of proteins, but sugars in the sticky substance make those proteins hard to study. Now, one scientist has figured out a way to pull proteins from the honey, revealing the world bees encounter.

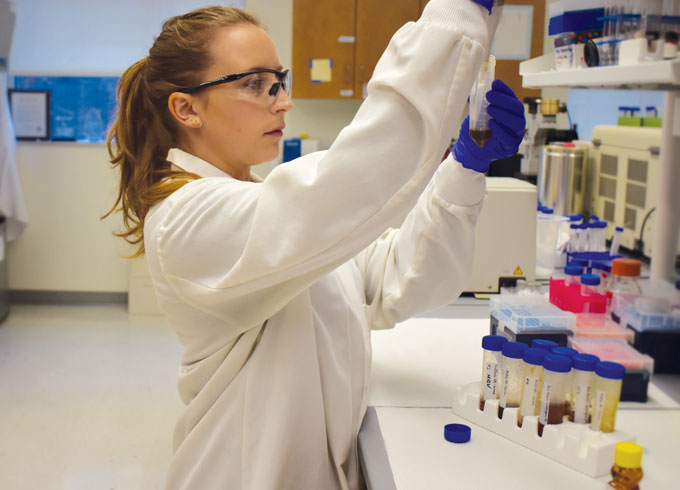

StudioSmart/Shutterstock

WASHINGTON — One scientist’s sweet tribute to her father may one day give beekeepers clues about their colonies’ health, as well as help warn others when crop diseases or pollen allergies are about to strike.

Those are all possible applications that biochemistry researcher Rocío Cornero of George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., sees for her work on examining proteins in honey. Cornero described her unpublished work December 9 at the annual joint meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology and the European Molecular Biology Organization.

Amateur beekeepers often don’t understand what is stressing bees in their hives, whether lack of water, starvation or infection with pathogens, says Cornero, whose father kept bees before his death earlier this year. “What we see in the honey can tell us a story about the health of that colony,” she says.

Bees are like miniature scientists that fly and sample a wide variety of environmental conditions, says cell biologist Lance Liotta, Cornero’s mentor at George Mason. As bees digest pollen, soil and water, bits of proteins from other organisms, including fungi, bacteria and viruses also end up in the insects’ stomachs. Honey, in turn, is basically bee vomit, Liotta says, and contains a record of virtually everything the bee came in contact with, as well as proteins from the bees themselves.

“The information archive in honey is unbelievable,” Liotta says. But until now, scientists have had a hard time studying proteins in honey. “It’s so gooey and sticky and hard to work with,” he says. Sugars in honey gum up lab equipment usually used to isolate proteins.

So Cornero developed a method to pull peptides — bits of proteins — out of honey using nanoparticles — a feat no other researchers have previously managed, Liotta says. Once extracted from the honey, the peptides are analyzed by mass spectrometry to determine the order of amino acids that make up each fragment of protein. Those peptides are then compared with a database of proteins to determine which organisms produced the honey proteins.

A group of high school students working at George Mason for the summer collected 13 honey samples from Virginia, Maryland. Two additional samples came from Cornero’s hometown of Mar del Plata in Argentina. The Argentine honey was from the last batches her father collected from his bees.

Proteins from bees, microbes and a wide variety of plants were among the components of the honey. Peptides in honey from one sample came from several bacteria, including some that normally live in bees’ guts and a few disease-causing varieties. Proteins from viruses and parasites that infect bees, including deformed wing virus and Varroa mites, which have been implicated in colony collapse disorder, were also found in the sample (SN: 1/17/18). Those results could mean bees from that location may have trouble surviving the winter when the insects’ immune systems are less able to fight infections.

Cornero also determined by looking at pollen and plant proteins in the honey that bees had pollinated a variety of plants, including sunflowers, lilacs, olive trees, red clover, potatoes and tomatoes. By analyzing pollen peptides, scientists may one day be able to learn whether claims that certain honey is made from wildflowers, clover or orange blossoms are really true.

What’s more, counting pollen peptides in local hives could, for example, give allergy sufferers a better idea of when hay fever is likely to flare in their area, Cornero says. The researchers also found plant virus proteins in the honey, an indication of the types of diseases that may be stalking local crops.

Next, Cornero hopes to develop a rapid protein test that would allow beekeepers to plunge a dipstick into honey and rapidly gauge their hives’ health. “Having my dad as a beekeeper, I know how beekeepers work, and it would be a great way to honor his work,” she says.