Male mice may serenade prospective mates at pitches about two octaves higher than the shrillest sounds audible to people.

This “mouse song” is comparable in complexity to the sequences of tones that songbirds and some whales make, say Timothy E. Holy and Zhongsheng Guo of Washington University in St. Louis.

Other researchers remain guarded about labeling mouse vocalizations as song. Nevertheless, says neurophysiologist Xiaoqin Wang of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, the discovery that mice emit richly patterned ultrasonic noises could have important implications for the study of communication.

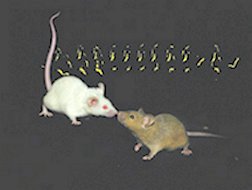

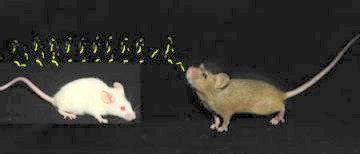

Scientists have known that mice produce ultrasound. When pups become isolated from their mothers, for example, they utter high-pitched cries that launch a maternal search-and-rescue operation. Adult males also vocalize when they detect female odors.

To investigate whether the adults make distinct syllables expressed in specific sequences, Holy and Guo recorded vocalizations by 45 male mice. The researchers placed the mice, one at a time, in a microphone-equipped chamber and inserted a urine-soaked cotton swab through a hole in one wall.

The investigators manipulated the resulting recordings to make ultrasonic noises audible to people (to listen to some samples, click here). The team used computer software to analyze the sounds.

Holy and Guo distinguished distinct syllable types according to, for example, how rapidly the sounds rose or fell in pitch. The animals emitted bursts of song containing about 10 syllables per second, the researchers report in the December PLoS Biology.

The mice repeated certain phrase sequences, creating acoustic motifs that meet established definitions of animal song, Holy and Guo conclude. Almost all the male mice in the study produced song, Holy says.

Neurobiologist Richard D. Mooney of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., says that the new “careful characterization” of mouse sounds provides a foundation for research that “could ultimately inform our understanding of speech.”

Mice could become useful models for studying mammalian communication because, unlike monkeys, they can be genetically manipulated with ease, says Wang, who studies monkey communication.

Wang acknowledges that male mice produce strings of vocalizations that appear to have intrinsic structure. “But the fact that [vocalizations] are not random doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re songs,” he cautions.

“I’m a little bit hesitant calling it song,” agrees Robert C. Liu of Emory University in Atlanta, who has studied mouse vocalizations. Learning is “a crucial element of song in the classic sense.”

While it’s not clear that mice learn to sing, Holy suspects that they do. He notes that individual males display their own characteristic singing patterns. These could reflect variations in learning.

Other key questions include why male mice make the noises and how females respond, says Mooney.

Holy says, “My guess is that it’s for the purposes of courtship.”