Baby starfish on the hunt whip up whirlpools

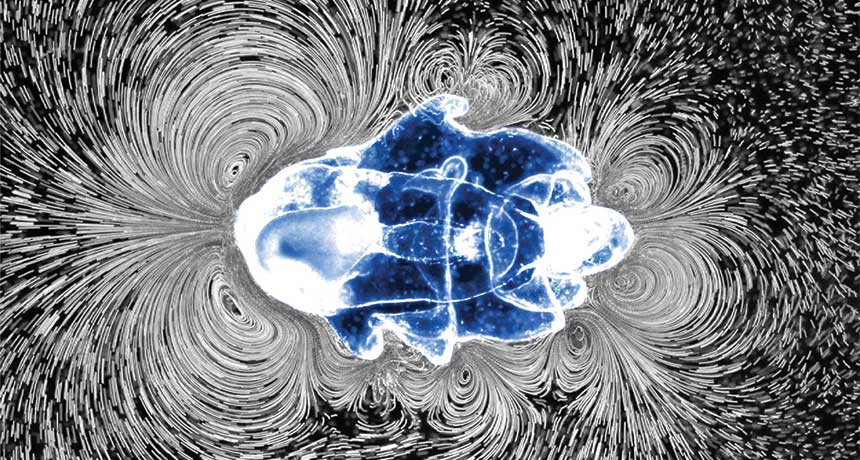

LUNCH BUFFET Swirling whirlpools are created by a starfish larva, shown in this time-lapse image. These vortices provide the larva with a conveyor belt of food, sucking in algae. Small beads suspended in water create trails showing fluid flow.

W. Gilpin, V.N. Prakash, M. Prakash/Nature Physics 2016