- More than 2 years ago

Even if your baby is very smart, he probably can’t read your mind — he might not even know you have one. New research suggests that infants as young as 7 months are sensitive to the perspectives of others. But more work is needed to demonstrate whether babies fully grasp that others have their own beliefs.

The new study, published December 24 in Science, adds to a large body of research exploring when humans first develop the capacity to infer the intentions and perspectives of others, a cognitive ability termed “theory of mind.” Scientists have long debated whether this is an innate ability or one that is arrived at as a young brain gathers information and experience.

Previous research suggested that kids can’t distinguish between what other people believe is going on from what is actually going on until the age of 4 or 5. This developmental milestone was explored in classic experiments where children see a boy, Maxie, put chocolate into a kitchen drawer. Maxie then leaves, and someone else comes in and moves the chocolate to a cupboard. Then Maxie comes back inside and wants his chocolate. The children are asked where Maxie will go: the drawer, where he thinks the chocolate is, or the cupboard, where it really is.

Young 3-year-olds say Maxie will go to the cupboard, says cognitive development specialist Josef Perner of the University of Salzburg, who conducted the Maxie experiments in the early 1980s. Even though Maxie doesn’t know the chocolate is in the cupboard, the 3-year-old viewers do and they apparently can’t yet grasp that where the chocolate is in reality may not be where Maxie thinks it is. “It’s only around 4 or 5 that children realize he doesn’t act according to how the world is, but acts according to his inner world.”

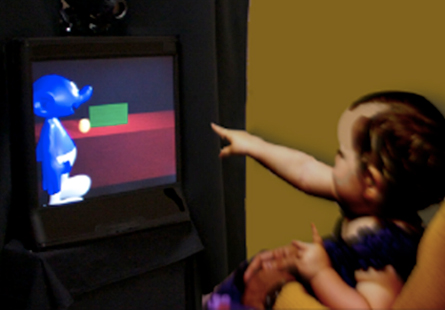

The new work involved similar experiments, also employing a “false belief” test that aims to get at whether infants understand that others can have a belief in their mind that doesn’t match reality. Seven-month-old babies watched a video of a Smurf-like creature that places on a table a ball, which rolls behind a partition or rolls out of view. The creature leaves, and the ball stays or moves again. When the creature comes back, the partition is lowered showing whether the ball is there. Sometimes the location of the ball is consistent with what the creature saw, but sometimes, as with Maxie and his chocolate, the creature has a false belief about the ball’s location, expecting the ball to be where the creature last saw it.

Babies looked at the screen longer when the creature’s expectations about the ball didn’t match where the ball actually was, the researchers report. This suggests that babies younger than age 1 are savvy about the beliefs of others, says Ágnes Kovács of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest, who led the new work.

Research does suggest that babies pay different attention to people than to objects, an outlook that’s important for developing a theory of mind. “Many recent studies show that infants have a more sophisticated understanding of others’ minds than we might have thought,” says developmental psychologist Alison Gopnik of the University of California, Berkeley. “They treat people as special from early on.”

But drawing conclusions about the thoughts of a being who can’t yet talk is fraught with difficulties, she notes. Using how long a baby looks at something can be an illuminating metric but needs to be combined with behavioral tests, such as a baby also reaching for a particular object, Gopnik says.

Perner notes that in the Maxie experiments, while the 3-year-olds stated that Maxie would go to the cupboard, they spent some time looking at the drawer, perhaps because their brains were trying to muddle through the conflicting ideas.

And he and others add that the design of the new study could have been stronger. For example, the experiment didn’t test how babies would react to watching the ball coming and going with no creature present.

Still, the work probes important questions, says Perner. “It’s still interesting because it shows that very young infants pay attention to the right kinds of things.”

It’s likely that there is no aha moment when children ‘get’ theory of mind, says Gopnik. “The most interesting question now is how children revise and change their early view of the mind based on the evidence they see around them,” she says. “Babies’ minds are far from being blank slates, but they aren’t written in stone either.”