Arctic warming bolsters summer heat waves

Slowing jet stream spawns weaker continent-cooling storms

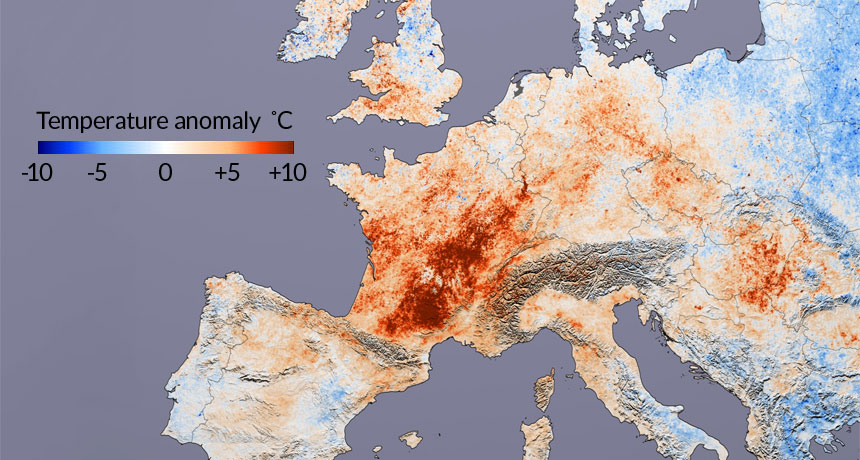

SCORCHING SUMMER The waning of summer storms due to Arctic warming can exacerbate summertime heat waves across the Northern Hemisphere, such as the record-setting summer 2003 season chronicled above in Europe, new research suggests. Red regions experienced hotter July temperatures than those measured in 2001.

NASA