African Legacy: Fossils plug gap in human origins

Three partial skulls excavated in eastern Africa, dating to between 154,000 and 160,000 years ago, represent the oldest known fossils of modern people, according to the ancient skulls’ discoverers.

The new finds of Homo sapiens fossils, unearthed near an Ethiopian village called Herto, fill a major gap in the record of our direct ancestors. Modern H. sapiens fossils previously found in Africa and Israel date to about 100,000 years ago. A skull excavated in Ethiopia of a not-yet-modern, so-called archaic H. sapiens is roughly 500,000 years old.

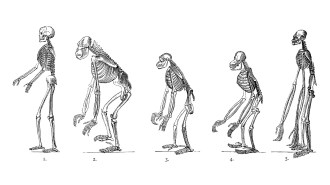

The Herto fossils show that H. sapiens evolved in Africa independently of European Neandertals, says project director Tim D. White, an anthropologist at the University of California, Berkeley. The finds thus bolster the out-of-Africa theory of human evolution (SN: 5/17/03, p. 307: Stone Age Genetics: Ancient DNA enters humanity’s heritage). In this view, people originated in Africa between 200,000 and 150,000 years ago and subsequently replaced Neandertals and other closely related groups.

In contrast, supporters of multiregional evolution argue that H. sapiens evolved over the past 2 million years with at least some interbreeding of African, Asian, and European populations.

“Only in the African fossil record can we now see a progression of specimens leading to modern humans,” White says.

At Herto in 1997, White’s team found the partial skulls of two adults, one of which retained its facial bones, and of a 6-to-7-year-old child. Removal of sediment from the fossils and their reconstruction, including the assembly of more than 200 pieces of the child’s cranium, occurred over the next 3 years.

Measurements of argon gas trapped in volcanic ash above and below the finds were used to generate an age estimate. The group describes the Herto discoveries in the June 12 Nature.

The investigators classify the skulls as members of a “near-human” H. sapiens subspecies. The face of the more complete adult specimen looked much like that of people today, they say. However, the braincase volume of the two Herto adults is smaller than that of archaic H. sapiens skulls and slightly larger than that of current populations.

At Herto, White’s team also unearthed skull pieces and teeth from seven other

H. sapiens individuals, more than 600 stone artifacts, and hippopotamus bones bearing stone-tool incisions made by humans either killing the animals or scavenging their carcasses. Geological analyses indicate that ancient Herto residents lived along the shores of a shallow lake inhabited by hippos, crocodiles, and catfish.

Stone-tool incisions on the Herto skulls probably resulted from removal of flesh after death and from other mortuary practices, White says. The smoothed edges of the child’s skull indicate that it was repeatedly handled.

“At last, we have well-dated evidence for the emergence of modern Homo sapiens in Africa,” remarks anthropologist G. Philip Rightmire of the State University of New York at Binghamton.

The only question remaining now is whether modern H. sapiens evolved first in eastern Africa or resulted from the mixing of archaic populations across Africa, adds anthropologist Christopher Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London, a backer of the out-of-Africa theory.

Multiregional-evolution proponent Milford Wolpoff of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor disagrees. Human fossils from later in the Stone Age exhibit signs of interbreeding among Africans and non-Africans, even if H. sapiens got its start in Africa, Wolpoff contends.

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, send it to editors@sciencenews.org. Please include your name and location.

To subscribe to Science News (print), go to https://www.kable.com/pub/scnw/

subServices.asp.

To sign up for the free weekly e-LETTER from Science News, go to http://www.sciencenews.org/subscribe_form.asp.