50 years ago, mysterious glass hinted at Earth’s violent past

Excerpt from the August 11, 1973 issue of Science News

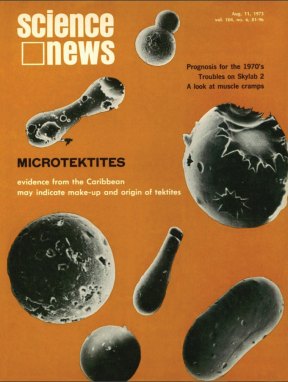

Like Hansel and Gretel followed a trail of breadcrumbs, scientists have followed glassy particles called tektites (some shown) to the sites of major meteorite impacts around the world.

rep0rter/iStock/Getty Images Plus