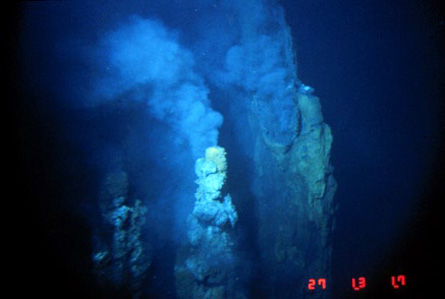

SAN FRANCISCO — Scientists have discovered an unusual kind of battery at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean: a living one, fueled by microbes that live near hydrothermal vents.

As they munch on noxious chemicals bubbling from the seafloor, these critters create electrical currents that flow through the walls of the chimneylike structures they inhabit.

“The amount of power produced by these microbes is rather modest,” said Harvard biologist and engineer Peter Girguis, who presented his research December 5 at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union. “But you could technically produce power in perpetuity.”

Girguis hopes to tap this power to run seafloor sensors. He and his colleagues measured the current by implanting an electrode in the side of an underwater chimney 2,200 meters below the surface at the Juan de Fuca Ridge off the Pacific Northwest coast.

To better understand the current’s source, the researchers built an artificial chimney in the laboratory. One tube that mimicked the inside of the chimney was filled with dissolved hydrogen sulfide, which smells like rotten eggs but is palatable to vent microbes. A second tube, outside of the chimney, contained only seawater.

The scientists grew a film of microbes on a piece of pyrite, a metallic mineral found in natural chimneys, that connected the two tubes. The current the microbes produced in the pyrite increased when they were given more food, suggesting this current is how the microbes make contact with the oxygen in the seawater outside of the chimney. Pyrite seems to shunt electrons created as the microbes break down hydrogen sulfide to these oxygen molecules, which react to form water.

Some microbes might make contact with oxygen directly in water that percolates through the pores of natural chimneys, suggests John Delaney, a marine geologist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Girguis agrees that’s possible but says it doesn’t rule out his “decisive” evidence that electrical currents help the creatures to, in human terms, breathe.

“This changes the way we think about metabolism at vents,” he said.