Evolutionary Back Story: Thoroughly modern spine supported human ancestor

Bones from a spinal column discovered at a nearly 1.8-million-year-old site in central Asia support the controversial possibility that ancient human ancestors spoke to one another.

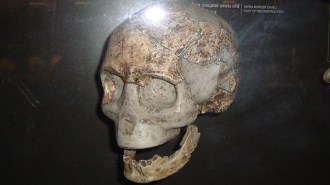

Excavations in 2005 at Dmanisi, Georgia, yielded five vertebrae from a Homo erectus individual, says anthropologist Marc R. Meyer of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The finds occurred in previously dated sediment that has yielded several skulls now attributed to H. erectus (SN: 5/13/00, p. 308: Available to subscribers at Fossils Hint at Who Left Africa First).

The new discoveries represent the oldest known vertebrae for the genus Homo, Meyer announced last week at the annual meeting of the Paleoanthropology Society in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The fossils consist of one lumbar, two thoracic, and two cervical vertebrae.

Meyer and his colleagues—David Lordkipanidze and Abesalom Vekua, both of the Georgian State Museum in Tbilisi—compared the size, shape, and volume of the Dmanisi vertebrae with more than 2,200 corresponding bones from people, chimpanzees, and gorillas.

“The Dmanisi spinal column falls within the human range and would have comfortably accommodated a modern human spinal cord,” Meyer says.

Moreover, the fossil vertebrae would have provided ample structural support for the respiratory muscles needed to articulate words, he asserts. Although it’s impossible to confirm that our prehistoric ancestors talked, Meyer notes, H. erectus at Dmanisi faced no respiratory limitations on speech.

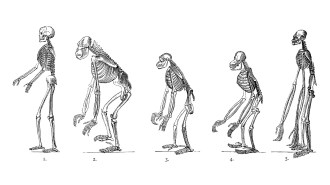

In contrast, the 1984 discovery in Kenya of a boy’s 1.6-million-year-old skeleton, identified by some researchers as H. erectus and by others as Homo ergaster, yielded small, chimplike vertebrae. Researchers initially suspected that the ancient youth and his presumably small-spined comrades lacked the respiratory control to talk as people do today.

In the past 5 years, investigators including Bruce Latimer of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History have suggested that the prehistoric boy offers a misleading view of H. erectus‘ backbone. They contend that growth of the bony canal encasing his spinal cord had been stunted, and spinal cord compression would have impeded his movement and caused limb weakness.

Finding ancient, humanlike vertebrae at Dmanisi fits with Latimer’s view, Meyer says. Infant malnutrition, which often arrests growth of the human vertebral canal, may have affected the H. erectus youth, Meyer suggests.

The ancient boy, who died at age 10 or so, would have required intensive protection and provisioning, Meyer asserts. “Both altruism and spoken language may have been part of the behavioral repertoire of early Homo,” the Pennsylvania researcher says.

The modern-looking vertebrae at Dmanisi, remarks David Frayer of the University of Kansas in Lawrence, comport with earlier fossil-skull studies indicating that early Homo possessed a speech-ready vocal tract.

Robert C. McCarthy of Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton disagrees. At the Paleoanthropology Society meeting, he presented vocal-tract reconstructions for various ancient Homo species suggesting that the capacity to articulate speech as well as people do now emerged exclusively in Homo sapiens around 50,000 years ago.

Before then, all members of the Homo genus—including H. sapiens—possessed a short set of neck vertebrae, resulting in a vocal tract with a restricted range of speech sounds, McCarthy and his coworkers argue.

Many populations today, including Australian aborigines, possess neck vertebrae comparable in length to those that McCarthy’s team considered inadequate for modern speech, Meyer responds.