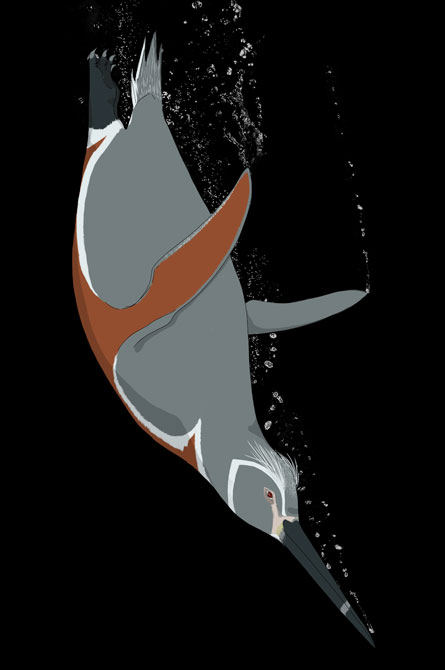

A fossil giant penguin with feathers reveals the first glimpse of what the well-dressed diving bird was wearing before tuxedos.

The 36-million-year-old fossils of the new species include a good portion of a skeleton with a skull and flipper, researchers report online September 30 in Science. Perhaps most exciting, though, are the fossilized feathers. They are so well preserved that scientists have been able to study the microscopic pigment-bearing nubbins called melanosomes that give the plumes their color.

“This is our first look at feathers in a fossil penguin,” says study coauthor Julia Clarke of the University of Texas at Austin.

Describing melanosomes in any kind of fossil is a development of just the last two years and “can provide a lot of new information about evolution,” says paleontologist Michael Benton of the University of Bristol in England, who was not part of the Peru study. Pigment structures can give clues to “themes that were virtually concealed from us without such direct evidence of ancient colors,” he says, such as how camouflage, warning signals and sexual displays evolved.

Found in northern Peru, the newly discovered penguin species weighed about 55 to 60 kilograms, or roughly twice what today’s emperor penguins average, Clarke estimates. Outweighing all living penguins, the species — now named Inkayacu paracasensis — ranks in the top five of whopper penguin species known from fossils.

When swimming, the bird stretched some 1.5 meters. Its skinny beak, about 23 centimeters long, outreaches modern penguins but resembles other fossil species.

The feathers and the flipper’s bone structure are adapted to swimming instead of flying, suggesting that some of the bigger changes in the evolution of penguinhood had already occurred.

But what Clarke and her colleagues can say so far about their new find suggests it was not a wedding-party bird in the formal black and white feathers that adorn many of today’s penguin species. Instead, the ancient penguins wore hues of soft grays and reddish browns, she says.

Clarke and her colleagues reconstructed the colors by looking at the size, distribution and proportion of the pigment structures. Paleontologists have linked some melanosome shapes in living birds with blacks, grays and other colors.

Modern penguins hadn’t had their melanosomes checked, so Clarke and her colleagues made a discovery there too. Eleven living species and one subspecies show clusters of big, plump melanosomes unlike those seen in other kinds of birds.

The pressures of the aquatic life may have favored the evolution of such hefty melanosomes, Clarke speculates. Melanosome pigments put the color in a feather, but Clarke notes that they can also strengthen a feather against fracturing. And this protection might matter to penguins, which “fly” in water, a substance 800 times denser than air, she says.

When her colleagues scrutinized the Peruvian penguin’s feathers though, it didn’t have these distinctive supersized melanosomes. A change as big as becoming a penguin, she says, doesn’t happen all at once.