- More than 2 years ago

Staying socially connected may be just as important for public health as washing your hands and covering your cough. A new study suggests that feelings of loneliness can spread through social networks like the common cold.

“People on the edge of the network spread their loneliness to others and then cut their ties,” says Nicholas Christakis of Harvard Medical School in Boston, a coauthor of the new study in the December Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. “It’s like the edge of a sweater: You start pulling at it and it unravels the network.”

This study is the latest in a series that Christakis and James Fowler of the University of California, San Diego have conducted to see how habits and feelings move through social networks. Their earlier studies suggested that obesity, smoking and happiness are contagious.

The new study, led by John Cacioppo of the University of Chicago, found that loneliness is catching as well, possibly because lonely people don’t trust their connections and foster that mistrust in others.

Loneliness appears to be easier to catch from friends than from family, to spread more among women than men, and to be most contagious among neighbors who live within a mile of each other. The study also found that loneliness can spread to three degrees of separation, as in the studies of obesity, smoking and happiness. One lonely friend makes you 40 to 65 percent more likely to be lonely, but a lonely friend-of-a-friend increases your chances of loneliness by 14 to 36 percent. A friend-of-a-friend-of-a-friend adds between 6 and 26 percent, the study suggests.

Not all networks researchers are convinced. Jason Fletcher of the Yale School of Public Health says that the studies’ controls are not good enough to eliminate other explanations, like environmental influences or the tendency of similar people to befriend each other. Fletcher has published a study (in the same issue of the British Medical Journal that reported that happiness is contagious) showing that acne, headaches and height also appear to spread through networks even though they are not likely to be transmitted socially.

“We’re on the side that [social contagion] exists — we’re not naysayers,” Fletcher says. “We just think the evidence isn’t clear enough on many of the outcomes.”

Despite its shortcomings, some researchers are enthusiastic about the study.

“I think this is a groundbreaking paper in loneliness literature,” says Dan Perlman, a psychologist at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro who specializes in loneliness. “Maybe there are people who are skeptical, but this is important work. I think that it should get a pat on the back.”

Christakis and Fowler examined data from a long-term health study based in Framingham, Mass., a small town where many of the study’s participants knew each other. The Framingham study followed thousands of people over 60 years, keeping track of physical and mental heath, habits and diet.

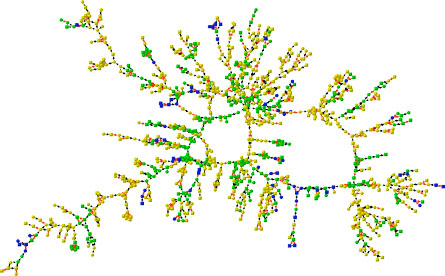

Each participant also named friends, relatives and neighbors who might know where they would be in two years, when it was time for the next exam. From this information, Christakis and Fowler reconstructed the social network of Framingham, including more than 12,000 ties between 5,124 people. The researchers plotted how reported loneliness, measured via a diagnostic test for depression, changed over time.

The results indicate that lonely people tend to move to the peripheries of social networks. But first, lonely people transmit their feeling of isolation to friends and neighbors.

Feeling lonely doesn’t mean you have no connections, Cacioppo says. It only means those connections aren’t satisfying enough. Loneliness can start as a sense that the world is hostile, which then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Loneliness causes people to be alert for social threats,” Cacioppo says. “You engage in more self-protective behavior, which is paradoxically self-defeating.” Lonely people can become standoffish and eventually withdraw from their social networks, leaving their former friends less well-connected and more likely to mistrust the world themselves.

Because loneliness is implicated in health problems from Alzheimer’s to heart disease, Cacioppo says, reconnecting to those who have fallen off the network may be vital for public health.