Rice Woes, Pt. 1

Mention cartels and thoughts immediately turn to drugs or oil. In short order, another cartel is expected to emerge, this one aimed at controlling production – and prices – of a commodity that may be even more in demand: rice.

A shortfall in this cereal’s production has been developing well under the radar screen of agricultural economists and growers. Although the International Rice Research Institute in Los Ba±os, the Philippines, had been warning for more than a decade that a rice crisis was looming, the expectation was that a big shortfall in production versus demand wouldn’t hit before 2010, notes Jan Leach, a rice scientist at (of all places) Colorado State University. Leach has an adjunct appointment at IRRI as well (where she flies off to tomorrow).

During the past 6 months, natural events have conspired to depress yields, but not global appetites for rice. Suddenly, this year found itself with demand outstripping supplies, Leach notes. Not surprisingly, the wholesale price of rice began to skyrocket.

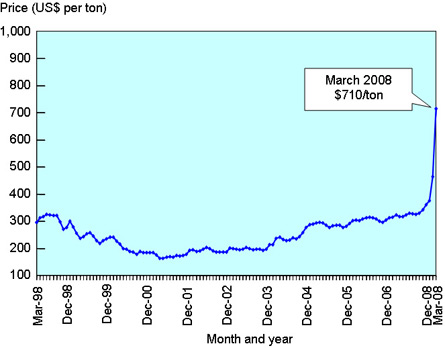

As recently as 2001 and ’02, rice exports could be purchased for roughly $200 (U.S.) a ton. By 2004 the grain had jumped to $300/ton, where it hovered for another four years. Then, this winter, problems developed in various parts of the world’s rice-growing regions, such as floods in Bangladesh and a plague of rice pests in Southeast Asia.

Panicked rice buyers began buying up whatever became available on the world market, Leach says. Together with rice demand exceeding production, rice prices spiked. By March 2008, they had reached $710/ton, IRRI reports. Just a week ago, Leach told me today, the price of rice in the Philippines topped $1,000/ton.

That’s good news for U.S. growers, who ship most of their harvests overseas. But they can’t grow enough to fill the gap because there are so many mouths to feed. Some 700 million people live on incomes of less than $1 a day in rice growing regions of Asia. They literally depend on this once-very-affordable source of calories. Typically, rice has supplied the poorest Asian families some 40 percent of their calories each day, IRRI reports; buying that rice ate up between 30 and 40 percent of their incomes.

The recent price hikes were predicted even if they arrived several years earlier than IRRI had anticipated. These price escalations, which disproportionately affect the globe’s poorest diners, “is a problem of our own making,” Leach says, referring to the developed world. Scientists could improve crop yields, she says, if the globe’s wealthiest nations hadn’t begun diminishing their funding of this work even as the problem was building. Indeed, she says, “I find it embarrassing and appalling that the First World is so far behind in funding agricultural research.”

IRRI data show that rice yields per area of land have stagnated for nearly two decades. Meanwhile, farmers have tapped virtually all of the land on which rice will grow. The result: Global yields began to stagnate at around 600 million tons of rice per year, roughly a decade ago.

“The depressing thing here,” Leach maintains, is that the only way that large proportions of the world’s poorest rice consumers will not be forced eventually to go to bed hungry “is if we make the plants on any given piece of land more productive.”

And the rub, of course, is that upping productivity comes from research that isn’t being supported amply. IRRI has productivity-enhancing varieties in the pipeline, but they must be crossbred with the rice types popular – and environmentally adapted to – a given local region. Transmission of advancements from the lab to plants in a farmer’s field typically takes between 5 and 15 years, Leach says. Meanwhile, IRRI anticipates that by 2010 – and certainly by 2025 – the demand for rice will surpass by perhaps 30 percent what global yields now deliver.

If food riots started to break out last month, imagine what might develop if shortfalls in a major source of calories for the planet’s poorest people begin leaving nearly one-third of those populations chronically and desperately hungry. For that reason, alone, Leach argues, the developed world can’t afford to continue underfinancing research on enhancing the productivity and disease resistance of rice – or maize and wheat.