Bacteria’s tail spins make water droplets swirl

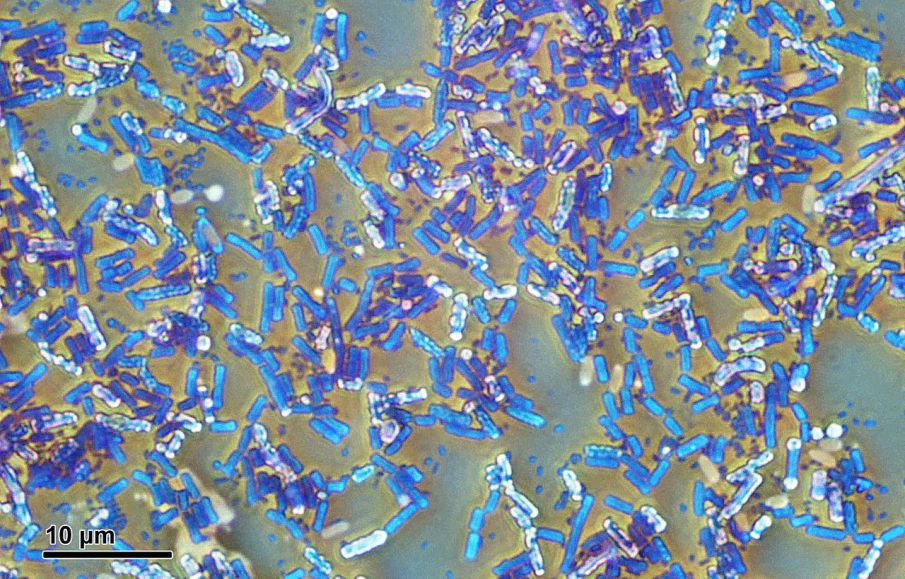

The way Bacillus subtilis bacteria swim in a single drop of water can spin the fluid into a spiraling vortex.

Josef Reischig/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY SA 3.0)

The way Bacillus subtilis bacteria swim in a single drop of water can spin the fluid into a spiraling vortex.

Josef Reischig/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY SA 3.0)