Domestic Disease: Exotic pets bring pathogens home

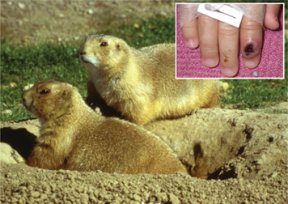

The current outbreak of monkeypox in the Midwest is the first report of this smallpox-related virus in people in the Western Hemisphere, according to infectious-disease investigators. It’s also the first time the disease has been associated with prairie dogs. However, the animals, caught wild in Texas and South Dakota and sold as pets, have been known to transmit other serious infections, the scientists say.

Since early May, monkeypox has sickened several dozen people, mainly in Wisconsin and Indiana, says Stephen Ostroff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

In central and western Africa, monkeypox appears naturally in some rodents and sometimes spreads to monkeys or people through bites or close contact with infected rodents. Monkeypox rarely moves from person to person.

There had been no human deaths in the U.S. outbreak as of press time, although in Africa the virus typically kills about 4 percent of people it infects. Initial symptoms in people include fevers, sweats, and headaches. Pus-filled blisters later form, burst, and heal into scars similar to those caused by chickenpox or smallpox.

Since only people carry or spread smallpox, the apparent link between symptoms in the first U.S. patient–a 4-year-old girl–and a prairie dog bite helped doctors at the Marshfield (Wis.) Clinic avoid mistakenly diagnosing the infection as the more deadly disease, says pathologist Kurt D. Reed of that clinic.

African studies show that smallpox vaccination reduces the risk of monkeypox infection by about 85 percent, but immunity wears off over time. At least one person infected in the current monkeypox outbreak received a smallpox vaccination several decades ago.

Because pet dealers catch prairie dogs in the wild, the animals can bring unusual diseases–including tularemia and plague–into the home. In the U.S. monkeypox outbreak, however, prairie dogs already in captivity probably caught the virus from a rodent that had been imported from Africa, says veterinarian Richard Hull of the Illinois agriculture department.

A company near Chicago that buys and sells exotic pets simultaneously held a sick Gambian giant pouched rat and some prairie dogs, Hull says. Prairie dogs that the company then sold to a pet dealer in Milwaukee later infected people. Some of the animals died or developed rashes, lost fur, and discharged fluid from their eyes and noses. Investigators are working to determine how the infection could have jumped between the two rodent species. In one case, a rabbit seems to have acquired an infection from a prairie dog at the veterinarian’s office and then infected its owner.

“Intermixing of species from the Old World and the New World . . . is just a setup for problems,” says Reed. Health and wildlife officials express concern that if infected animals escape into the wild, monkeypox might join the roster of diseases established in North America. To prevent that, officials in several states have prohibited the release of pet prairie dogs into the wild.

In 1999, West Nile virus became the most recent infection known to gain a foothold among wild animals in North America. Earlier this year in China, investigators traced the virus causing severe acute respiratory syndrome to the civet, a wild mammal.

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, send it to editors@sciencenews.org. Please include your name and location.