Newly released radar images gathered during a flight of the space shuttle Endeavour 3 years ago show what previous orbital photos haven’t–the subtle topography related to the impact of an asteroid or comet that may have wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

The original impact site lay beneath the waters of the ancient Caribbean. Sediments slowly filled in the 180-kilometer-wide crater, and subsequently, tectonic forces lifted part of the crater above sea level. Today, what’s left of the Chicxulub crater, which is named for the fishing village near its center, straddles the northwest coast of Mexico’s Yucatn peninsula.

Spaceborne instruments and earthbound geologists have detected gravitational and magnetic anomalies surrounding the ancient ground zero (SN: 6/15/02, p. 378)

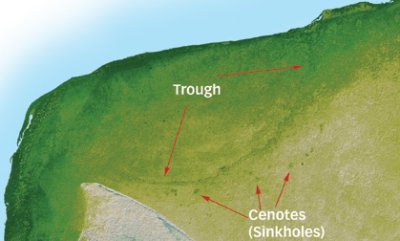

Until now, however, direct visual evidence of the killer crater hadn’t shown up on images taken from space, says planetary scientist Michael Kobrick of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Data garnered in February 2000 depict a 5-km-wide trough on the peninsula that roughly coincides with the crater’s outer rim. That broad moat is typically no more than 5 m deep, a variation that’s easy to miss across a large, forest-covered distance, says Kobrick.

Cenotes, or water-filled sinkholes, also dot the new radar map. These small, circular depressions form when large caverns in the limestone sediments at and around the crater’s rim collapse.

The shuttle data that unveiled the extraterrestrial blemish on the Yucatn are just part of the nearly 1 trillion radar measurements made of Earth between latitudes of 60N and 56S. Those data points, spaced an average of 90 m apart, cover a swath that stretches from the latitude of Seward, Alaska, and St. Petersburg, Russia, to points just north of Antarctica. NASA previously released topographical data for the continental United States (SN: 2/23/02, p. 126: Shuttle yields detailed, 3-D atlas) and will next publish detailed maps of South America.

Chicxulub’s subtle trough had been noted by scientists surveying the area, but those measurements took years to acquire and were widely spaced, says Mark Pilkington, a geophysicist with Natural Resources Canada in Ottawa. The new high-resolution map undoubtedly improves on ones compiled from those sources, he notes.

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, please send it to editors@sciencenews.org.