New HIV inhibitor

Drug blocks the most resistant forms of the virus from replicating

- More than 2 years ago

A new HIV drug can, when combined with other therapies, suppress even the most drug-resistant strains of the virus that causes AIDS, scientists report in two papers in the July 24 New England Journal of Medicine.

The study looks at one group of HIV patients for whom the standard, clinically approved HIV medications are not working.

“These people are very sick, and they have few if any other treatment options because they have a form of HIV that is resistant to just about any clinically approved medication,” says study coauthor Jeffrey L. Lennox, who directs the HIV/AIDS care clinic at GradyMemorialHospital in Atlanta. “Without this new drug, some of the patients might not be with us today.”

When combined with other anti-HIV medications, the drug, raltegravir, was an effective treatment for patients in the study, Lennox says.

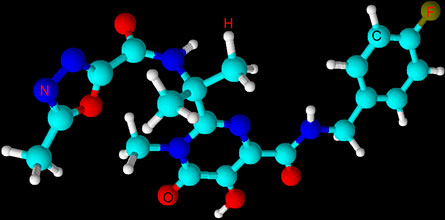

The MERCK drug is the first in a novel class of antiretroviral drugs called integrase inhibitors, which disrupt the virus’s ability to integrate its DNA into uninfected cells. If the virus cannot infect healthy cells with its genetic material, the virus cannot replicate and continue to spread throughout the body.

“I was impressed with how potent raltegravir proved to be for a group of patients that are hardest to treat,” says Steven Johnson, chief of the University of Colorado Denver’s HIV clinic in Aurora, who was not involved in the new studies.

The study led to FDA approval of raltegravir last year, Lennox notes. As with many clinical trials, the FDA reviewed the studies’ unpublished data after patients had been taking raltegravir in combination with other drugs for 24 weeks. Researchers measured patients’ levels of HIV in the blood, and patients taking raltegravir showed a significant reduction in their virus levels compared with those taking a placebo in combination with other antiretroviral drugs. Because of the promise raltegravir showed, early in the studies, the administration fast-tracked the HIV-suppressor for clinical use in October of 2007, Lennox says.

“These newly reported data out to week 48 confirm the 24-week results that led to regulatory approval for clinical use,” says MERCK scientist Bach-Yen Nguyen.

In order to participate, patients needed to have more than 1,000 copies of HIV-1 RNA per milliliter of blood while receiving antiretroviral therapy. After 48 weeks, 62.1 percent of raltegravir recipients had HIV-1 RNA levels below 50 copies per milliliter of blood compared with 32.9 percent in the placebo group.

While the first paper reports on the efficacy and safety of raltegravir, the second looks at the virus’s ability to grow resistant to the new drug.

Some study patients became resistant even to the new drug, especially when it was used without other anti-HIV medications. Johnson says the finding reinforces the practice of treating HIV with a combination of medications.

The researchers also report that the group taking the new drug had slightly higher rates of cancer than the control group. Cancers were detected in 3.5 percent of patients taking raltegravir, while 1.7 percent of placebo-taking participants showed cancer growths. Longer term studies are needed to watch for these problems, Johnson says, but “the benefits likely outweigh the risks.”