- More than 2 years ago

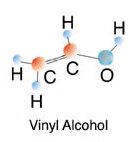

Astrochemists have discovered another organic chemical in the same region of space

where other researchers had identified the first extraterrestrial sugar (SN:

6/24/00, p. 405). On Earth, the alcohol is used to make packaging polymers.

The finding of space-based molecules such as sugar and the newly identified vinyl

alcohol could help researchers determine how complex molecules first formed in the

cosmos, says Barry Turner of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in

Charlottesville, Va. The findings will appear in a forthcoming issue of

Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Turner and A.J. Apponi of the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory in

Tucson found vinyl alcohol near the center of the Milky Way in the gas and dust

cloud Sagittarius B2. The astrochemists used the 12 Meter Telescope on Kitt Peak

near Tucson to detect the molecule’s characteristic radio emissions.

“Scientists understand these regions of space very poorly,” says Eric Herbst of

Ohio State University in Columbus. “The more data we have, the better,” he says.

Researchers say that most extraterrestrial molecules form when atoms and small

molecules collide in interstellar gas clouds. But such reactions can’t efficiently

produce molecules with the modest complexity of vinyl alcohol, which has seven

atoms, says Lewis E. Snyder of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Instead, many astronomers suspect that such molecules form on dust grains.

Vinyl alcohol could offer extra insight into space chemistry because it’s part of

a molecular trio in which the other members already have been found in space, says

Turner. Acetaldehyde, ethylene oxide, and vinyl alcohol are isomers–they have the same atoms but in different arrangements.

“I think it’s becoming clearer that isomerization in space is important” for

understanding extraterrestrial chemistry, notes Jan M. Hollis of NASA’s Goddard

Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. When he and his colleagues found sugar in

Sagittarius B2 last year, that molecule completed the first known cosmic isomeric

triplet. The other members are acetic acid and methyl formate, already known space

residents.

Finding the last member of an isomer set is “like completing the inventory,” notes

Steven Charnley of NASA’s Ames Research Center in Mountain View, Calif.

Understanding how such isomers form in space could help researchers learn how even

larger molecules form.

Snyder says he’s particularly interested in whether space chemistry can produce

complex molecules that could have jump-started life on Earth.