Two teenagers have once again proved an ancient math rule

Ne’Kiya Jackson and Calcea Johnson proved the Pythagorean theorem using trigonometry

Ne’Kiya Jackson (left) and Calcea Johnson (right) recently published 10 new trigonometry-based proofs of the Pythagorean theorem that they developed while in high school.

Calcea Johnson

Two years ago, a couple of high school classmates each composed a mathematical marvel, a trigonometric proof of the Pythagorean theorem. Now, they’re unveiling 10 more.

For over 2,000 years, such proofs were considered impossible. And yet, undeterred, Ne’Kiya Jackson and Calcea Johnson published their new proofs October 28 in American Mathematical Monthly.

“Some people have the impression that you have to be in academia for years and years before you can actually produce some new mathematics,” says mathematician Álvaro Lozano-Robledo of the University of Connecticut in Storrs. But, he says, Jackson and Johnson demonstrate that “you can make a splash even as a high school student.”

Jackson is now a pharmacy student at Xavier University of Louisiana in New Orleans, while Johnson is studying environmental engineering at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge.

Mathematical proofs are sequences of statements that demonstrate an assertion is true or false. Pythagoras’ theorem — a2 + b2 = c2, relating the length of a right triangle’s hypotenuse to those of its other two sides — has been proven many times with algebra and geometry (SN: 4/2/03).

But in 1927, mathematician Elisha Loomis asserted that the feat could not be done using rules from trigonometry, a subset of geometry that deals with the relationships between angles and side lengths of triangles. He believed that Pythagoras’ theorem is so fundamental to trigonometry, any trigonometry-based attempt to prove the theorem would have to first assume it was true, thereby resorting to circular logic.

Jackson and Johnson conceived the first of their trigonometry-based proofs in 2022, while seniors at St. Mary’s Academy in New Orleans, a Catholic school attended mostly by young Black women. At that time, only two other trigonometric proofs of Pythagoras’ theorem existed, presented by mathematicians Jason Zimba and Nuno Luzia in 2009 and 2015, respectively. Working on the early proofs “sparked the creative process,” Jackson says, “and from there we developed additional proofs.”

After formally presenting their work at an American Mathematical Society meeting in March 2023, the duo set out to publish their findings in a peer-reviewed journal. “This proved to be the most daunting task of all,” they said in the paper. In addition to writing, the duo had to develop new skills, all while entering college. “Learning how to code in LaTeX [a typesetting software] is not so simple when you’re also trying to write a 5-page essay with a group, and submit a data analysis for a lab,” they wrote.

Nonetheless, they were motivated to finish what they started. “It was important to me to have our proofs published to solidify that our work is correct and respectable,” Johnson says.

According to Jackson and Johnson, trigonometric terms can be defined in two different ways, and this can complicate efforts to prove Pythagoras’ theorem. By focusing on just one of these methods, they developed four proofs for right triangles with sides of different lengths and one for right triangles with two equal sides.

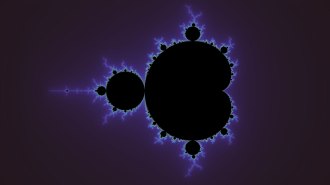

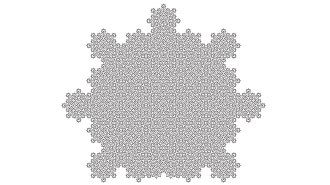

Among these, one proof stands out to Lozano-Robledo. In it, the students fill one larger triangle with an infinite sequence of smaller triangles and use calculus to find the lengths of the larger triangle’s sides. “It looks like nothing I’ve ever seen,” Lozano-Robledo says.

Jackson and Johnson also leave another five proofs “for the interested reader to discover,” they wrote. The paper includes a lemma — a sort of stepping-stone to proving a theorem — that “provides a clear direction towards the additional proofs,” Johnson says.

Now that the proofs are published, “other people might take the paper and generalize those proofs, or generalize their ideas, or use their ideas in other ways,” Lozano-Robledo says. “It just opens up a lot of mathematical conversations.”

Jackson hopes that the paper’s publication will inspire other students to “see that obstacles are part of the process. Stick with it, and you might find yourself achieving more than you thought possible.”