‘Echidnapus’ hints at a lost age of egg-laying mammals

The extinct creature's bizarre mix of features are reminiscent of platypuses and echidnas

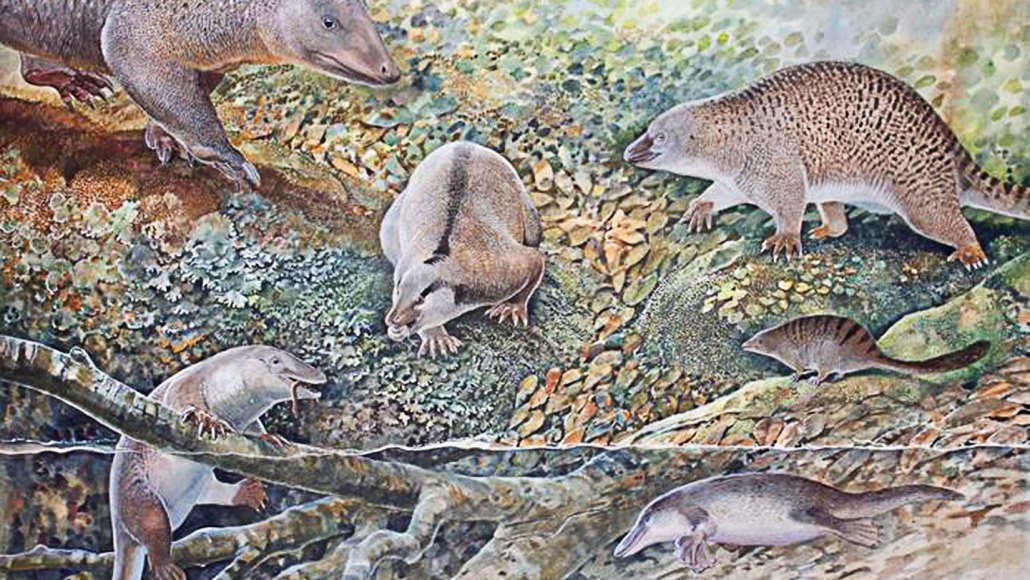

About 100 million years ago, a diverse community of egg-laying mammals inhabited Australia. The six known species, three of which are newly described, are shown in this artist’s rendition. Clockwise from lower left: Opalios splendens, or “echidnapus;” pig-sized Stirtodon elizabethae; Kollikodon ritchiei; Steropodon glamani; rat-sized Parvolapus clytiei; and Dharragarra aurora, the earliest known platypus.

PETER SHOUTEN