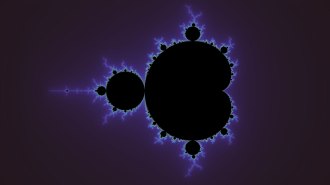

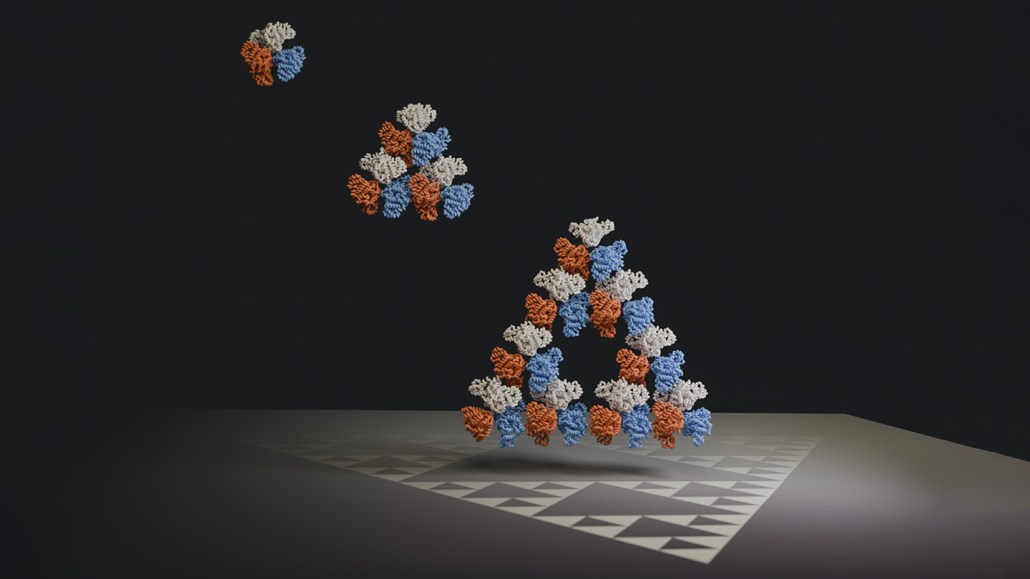

Scientists find a naturally occurring molecule that forms a fractal

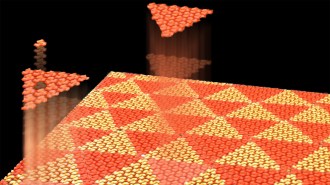

The protein assembles itself into Sierpiński triangles

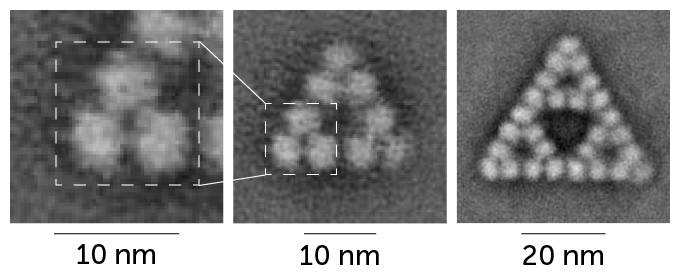

Researchers have found a bacterial protein that links up to form a type of fractal called a Sierpiński triangle (illustrated). It’s the first known case of a naturally occurring regular fractal on the molecular level.

Franziska Sendker