Measles got a foothold in the United States this year and almost didn’t let go

Areas of low vaccination are blamed for the virus’s almost 12-month stay

The first half of 2019 had more reported measles cases globally than in any year since 2006. This baby in the Philippines has the telltale rash.

James Goodson/CDC

- More than 2 years ago

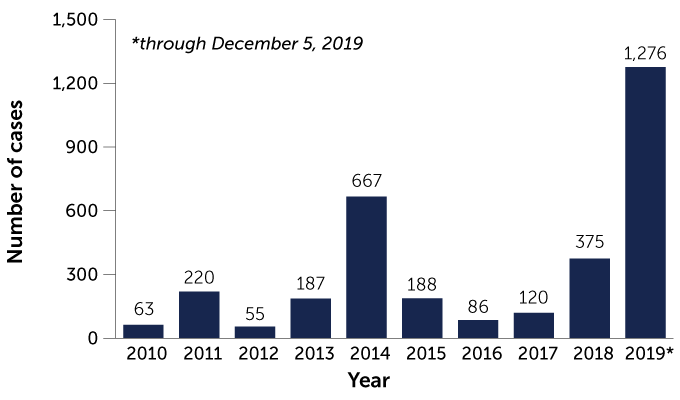

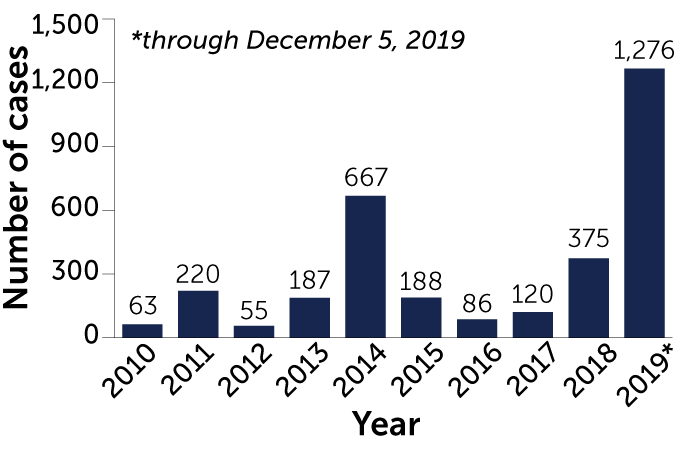

In 2019, measles sickened more people in the United States than in any year since 1992. As of December 5, there were 1,276 illnesses reported in 31 states. Two outbreaks in New York accounted for the lion’s share: more than 75 percent of the cases.

The New York outbreaks, which began in the fall of 2018, ran almost long enough to strip the United States of its measles elimination status, which it achieved in 2000. To receive that designation from the World Health Organization, a country must go a year without the disease spreading continuously in an area within its borders.

There have been U.S. outbreaks since 2000 — most notably, 667 cases in 2014 — but none had threatened to undo elimination (SN Online: 10/4/19). The outbreak in New York City ended on September 3. The other New York outbreak, in Rockland and neighboring counties, ended in early October.

“The best way to stop this and other vaccine-preventable diseases from gaining a foothold in the U.S. is to accept vaccines,” Robert Redfield, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, said in an October 4 statement announcing that the nation was holding on to its elimination status.

Measles flare-up

As of December 5, the United States saw 1,276 measles cases in 2019, almost double the number of the record-breaking outbreak of 2014.

U.S. measles cases by year

Source: CDC

Many other countries struggled with measles outbreaks this year (SN: 6/8/19, p. 22). As of November 17, Congo had the largest outbreak, with an estimated 250,000 measles cases and more than 5,000 deaths, mostly children under 5. Samoa, with immunization rates as low as 31 percent, was hit hard late in 2019, with more than 3,700 cases and dozens of deaths.

As in previous years, travelers launched the recent U.S. measles outbreaks, bringing the virus into the country and spurring infections in places where immunization rates were lower than 92 to 95 percent, the threshold needed to prevent a measles outbreak (SN Online: 4/15/19). This herd immunity protects the unvaccinated, including those who can’t be vaccinated, such as infants or people who have weak immune systems.

In 1978, the United States embarked on what became a decadeslong effort to eliminate measles, which included an immunization program that requires children be vaccinated to enter school and helps defray the cost of vaccination for eligible children. Yet parents who delay or avoid vaccinating their children — by seeking exemptions for religious or personal beliefs — leave their communities vulnerable. About 90 percent of the U.S. cases in 2019 occurred in people who had not been vaccinated or didn’t know if they had been. Doctors are exploring how to find common ground with vaccine-hesitant parents to encourage vaccination (SN: 6/8/19, p. 16).

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

Many people aren’t aware of the toll that measles can take, says Yvonne Maldonado, a pediatric infectious disease expert at Stanford University School of Medicine. She has seen children with measles develop pneumonia and encephalitis, a dangerous brain swelling. And measles can wipe out immune memory, raising a person’s risk for other infections (SN Online: 10/31/19).

Future U.S. outbreaks are likely, says William Moss, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The United States still has communities where there’s a high enough number of susceptible individuals to ignite an outbreak. “We can’t let our guard down,” he says. “Measles will find its way back.”

Good news on other infections

This year saw progress against several dangerous infectious diseases.

Tuberculosis: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a new antibiotic for use with two other drugs to treat a particularly deadly form of drug-resistant tuberculosis (SN: 9/14/19, p. 6).

Ebola: In November, European regulators approved an Ebola vaccine that was used during the recent Congo outbreak, which started in August 2018. In a study in patients infected with the virus, conducted amid that outbreak, two therapies proved effective at preventing death (SN Online: 8/12/19). (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which makes one of the treatments, is a major financial supporter of Society for Science & the Public, which publishes Science News.)

Chlamydia: The first vaccine candidate against chlamydia, one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases, passed its first test in healthy women (SN: 9/14/19, p. 6). Two versions of the vaccine safely produced an immune response, while a placebo had no effect.