Light All Night

New images quantify a nocturnal pollutant

Ansel Adams once called his photography of the nation’s parklands a “blazing poetry of the real.” If scientific data were verse, that description would also fit Chad Moore’s pictures. Taken in dozens of national parks, mostly in the western United States, Moore’s images emphasize contrast, horizon, and sky. But they aren’t imitations of Adams’ art. In the name of science, Moore photographs the darkness, but his subject may be in peril.

Moore’s data demonstrate that artificial light from urban areas penetrates deep into some of America’s most remote, wild places. For species and ecosystems that have evolved with a nightly quota of darkness, light pollution can be a force of ecological disruption, other research has suggested. With the new images, ecologists can identify geographic areas where sensitive species are most likely to be affected. The inventory of images also provides a reference point for measuring future changes in light pollution, Moore says.

Most of this light originates in cities as illumination from buildings and streets. Light reflects off moisture and dust in the air, creating “sky glow,” says ecologist Travis Longcore of the Urban Wildlands Group in Los Angeles. In some places, it obscures the starlight.

Depending on the light’s intensity, the cloud cover, and other factors, a city’s sky glow may be visible hundreds of kilometers away, says Moore. At such distances, the curvature of Earth can obscure whatever buildings and structures originally emitted the light. Extending from the city in all directions, the light from Las Vegas, for example, reaches 8 of 38 parks that Moore has surveyed.

About 150 km away from Las Vegas, the city’s lights are the dominant cause of light pollution in Death Valley National Park, where Moore’s collaborator Dan Duriscoe works. On the other hand, “we can barely detect Las Vegas from Bryce Canyon,” about 300 km away, says Moore, who’s based in Utah at that national park.

Some images created by Moore and Duriscoe appear here for the first time in print. The physical scientists published other new pictures this week at http://www2.nature.nps.gov/air/lightscapes.

Moore and Duriscoe gathered their data with a commercially available astronomical-grade camera that they’ve customized. From a stationary position, their automated digital camera photographs every corner of the sky by taking at least 45 overlapping exposures in about half an hour.

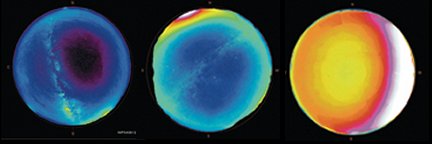

On a computer, Duriscoe weaves together the exposures to form a single mosaic of the heavens. In some images, he then enhances the contrast with false color to show bright light in white, reds, and oranges and near darkness in cooler shades. The resulting data set can be displayed as a panorama or in fish-eye–view format.

“You can think of each pixel as a cell in a spreadsheet,” Moore says.

These photos can quantify, for example, the light shining on Nevada’s Great Basin National Park. The slight glow from Las Vegas, more than 300 km to the south, is one of the most prominent features in that park’s firmament on a moonless night. Yet, Great Basin, says Moore, “is as close as we have gotten to pristine.

At most of the sites that the researchers have surveyed, nearer and often brighter sources of light abound. Compared with the total illumination documented at Great Basin, a site called Government Wash (third photo from top) in Lake Mead National Recreation Area in Nevada showed about 10 times as much light, Duriscoe notes. “The brightest part of the sky at Great Basin equals the darkest part of the sky at Government Wash,” he says.

Vanishing acts

For now, a gap remains between the new measurements of artificial light and documentation of its biological effects. But effects may be afoot. For example, the disappearance of several populations of snakes in the increasing glow of the southern California skyline hints at light as the culprit.

Decades ago, the California glossy snake was perhaps the most abundant reptile in southern California. But habitat destruction and other threats pushed the wide-ranging, nocturnal species into steep decline, according to zoologist Robert Fisher of the U.S. Geological Survey in San Diego.

“We’ve gone back to places where it was widespread, and we can’t find it in most of those places,” he says.

To conduct a rough census of snakes in undeveloped areas near San Diego and Los Angeles, Fisher and his USGS colleague Ted Case set catch-and-release traps in nature reserves that have large, contiguous areas not traversed by roads.

In many such places, the researchers collected large numbers of diurnal snakes that need essentially the same habitat and range as the nocturnal California glossy does. But the glossies were gone.

“The reserves seem large enough to maintain them, but they don’t seem to be there,” Fisher says. The problem, he suggests, must be “some external factor.”

A major candidate is light, he says.

The researchers found healthy populations of glossies in two remnants of the snake’s former range. Each spot—El Monte Canyon and Camp Pendleton—is largely shielded from the lights of the region’s urban centers by a combination of topography and distance, Fisher says.

Also in southern California, the western long-nosed snake appears to be declining, at least in part because of light pollution, Fisher and Case note.

Light may be edging out the snakes even where humanmade structures have not encroached on their habitat. “It might be that you can protect the land, but unless you can control the light levels that are invading the land, you’re not going to be able to protect some of the species,” Fisher says.

He presents some of the data that he and Case collected in a chapter in Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting (Island Press, 2006).

That new volume, edited by Longcore and Catherine Rich, also of the Urban Wildlands Group, devotes other chapters to the effects of light pollution on mammals, birds, fishes, and invertebrates. Contributing scientists note, for example, that light may interfere with mating activity among diverse nocturnal species, disrupt moth predation by bats, and discourage zooplankton from feeding on algae.

Four years ago, Rich and Longcore organized the first conference on ecological effects of light pollution (SN: 4/20/2002, p. 248: Deprived of Darkness).

Hunkered down

In a recent survey, Bryant Buchanan and Sharon Wise of Utica College in New York strung up lines of white Christmas lights in woodlands in rural Virginia. They switched on the lights at dusk and scoured the illuminated tracts for red-backed salamanders, which are common nocturnal insectivores that hide when they’re not hunting. The researchers also counted salamanders in nearby tracts that weren’t lit.

During the first 2 hours after nightfall, the researchers found that more salamanders were active in the darker areas than in the lit ones. Later in the night, that difference disappeared.

About 0.01 lux of light struck the forest floor in the lit areas during the experiment. That’s more than the amount shed onto the ground by the moon but less than natural twilight provides, Buchanan and Wise note in a chapter of the recent book.

If such modest illumination can delay salamanders’ nightly feeding excursions, Wise says, then “artificial night lighting has the potential to shorten foraging periods, limit food intake, and depress rates of growth, reproduction, and survival.”

Red-backed salamanders are far from endangered. But rarer species might also hunker down when lights are bright, Wise says. Decades-old research shows that diverse amphibians calibrate their activity to the moon’s cycles and that they’re least active when the moon is brightest.

At the most light-polluted sites where Moore and Duriscoe have collected data, sky glow outshines the moon for nearly half of each month.