- More than 2 years ago

The July afternoon was oppressively hot in Dayton, Tenn. After a steamy morning session in the county courthouse, the judge had ordered that the trial of teacher John T. Scopes be moved outdoors. As the afternoon wore on, more and more townspeople joined the crowd, which eventually numbered at least several hundred. It was the final day before the case was to go to the jury, and, in a calculated move, lead defense attorney Clarence Darrow, 68, called William Jennings Bryan, a member of the prosecution team, to testify for the defense. A famed orator and 3 years younger than Darrow, Bryan was the leader of a fundamentalist campaign against the teaching of human evolution in schools. In dappled shade, Bryan sat in a chair as Darrow stood nearby, firing question after question at the witness. It would become one of the most famous scenes in U.S. legal history. Bryan himself fell ill and died just 6 days later.

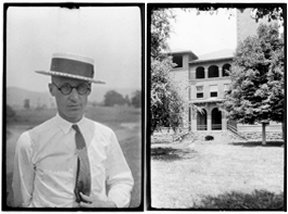

As the 2-hour interrogation proceeded, a photographer captured the scene: Bryan’s face as he did his best to answer a question and Darrow as he waited to pounce, thumbs pulling casually on his suspenders. The photographer’s name was Watson Davis, managing editor of Science Service (the publisher of what is now Science News). Davis was one of two Science Service reporters covering the 10-day 1925 trial and writing articles for distribution to newspapers around the country.

A photo buff, Davis had brought along his camera to record not only such climactic moments but also the people and locations related to the trial. However, the dozens of photos were never published. First in a file at Science Service’s offices and later tucked into a box at the Smithsonian Institution Archives in Washington, D.C., the negatives remained forgotten until they were recently found by independent historian Marcel C. LaFollette, who lives in Washington.

“These stunning photographs are the discovery of a lifetime,” LaFollette says. She is now writing a book about the Scopes trial, focusing on the photographs that she uncovered.

LaFollette’s “incredible find is a wonderful example of how hard it is to predict what the value of an archive will be,” says science historian Bruce Lewenstein of Cornell University, “and why more science-oriented organizations should put effort into preserving their records.”

Huge collection

The box containing the Scopes-trial negatives was one of several hundred holding photos, correspondence, and many other Science Service records.

Founded in 1921 as a not-for-profit organization, Science Service aimed to increase and improve the public dissemination of scientific and technical information. Initially, it was a daily news service offering articles to client newspapers. The bulk of these stories was combined weekly into magazine form as the Science News-Letter, which was available to subscribers.

The organization later expanded into microfilm, movies, and offerings for magazines and radio. It also began various educational programs, ranging from the Science Clubs of America and “Things of Science” activity kits to the Westinghouse (now Intel) Science Talent Search.

In 1971, Science Service donated its records, up to the year 1965, to the Smithsonian. The collection was so large, however, that the Smithsonian didn’t have the resources to sort, integrate, and index the records. “For a very long time, just a cursory inventory was available,” says Tammy Peters, supervisory archivist at the Smithsonian Archives.

Nonetheless, in the mid-1970s, the materials were a valuable resource for David Rhees, then a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and now director of the Bakken Library and Museum of Electricity in Life in Minneapolis. For his 1979 master’s thesis, Rhees examined the first decade of Science Service’s existence.

“Part of the great fun of my project was reading through a decade’s worth of issues of the Science News Bulletin and Science News-Letter,” Rhees says. “You could really capture the excitement of science in the Roaring ’20s through those pages, and since Science Service had a board of trustees of very distinguished scientists, its reporters had access to all the leaders of the scientific profession.”

In delving into the collection, Rhees was most thrilled to discover a telegram that reporter Frank Thone had sent directly from the Scopes trial to Edwin Slosson, who then headed Science Service. Both Thone and Davis filed daily reports from Dayton for the duration of the trial.

“The Scopes trial was one of the biggest science stories of the twentieth century, and the telegram, in its clipped, well, telegraphic style, connected me to the excitement and immediacy of this earthshaking story,” Rhees says.

In 1994, former Science Service staff member Jane Livermore volunteered to start cataloging and sorting the collection. LaFollette helped complete that task, developing an annotated and illustrated contents list of all the boxes. The list, called a finding aid, is now available online at http://www.siarchives.si.edu/research/scienceservice.html.

“There is wonderful material on censorship in World War II, extraordinary material on the development of physics, papers related to the early history of the National Association of Science Writers, and much more,” LaFollette says, adding that it’s all relevant to the history of science communication.

Says Peters, “LaFollette helped us see the collection’s significance. You can look at the collection from many different angles. It tells you what was happening in science and what was happening around the world. You can check for any topic in science and see how it was handled.”

Dateline Dayton

The Scopes trial was important to Science Service financially. Newspapers paid for articles from the trial, and these funds helped support the struggling organization.

Science Service also played a role behind the scenes, aiding Darrow’s defense team. The Science Service staff helped coordinate the gathering of scientific experts on evolution to testify at the trial. It also distributed a series of articles, written by prominent scientists, explaining and defending evolution.

Davis made two trips to Dayton. In June, before the trial started, he made a detour to Dayton as part of a previously planned trip west. He took one set of photos during this visit, including pictures of Scopes himself and various places, such as the school where Scopes taught and the drugstore where a group of Dayton civic leaders had met and decided to challenge Tennessee’s new statute against teaching evolution.

Davis returned to Dayton in July, accompanied by Thone, for the full 10 days of the trial. The two reporters wrote daily reports about the trial for various clients. “They made enough from their wire service clients to cover their expenses,” LaFollette says. “Producing news that [Science Service] could sell was always the crucial thing in those first 20 years.”

As well as reporting, Davis took additional photos during the trial, including several of the confrontation between Darrow and Bryan on the second-to-last day. By that time, many reporters had already left town, anticipating that nothing much more would happen.

“Davis was a sort of friend of the defense team, so he was sitting or standing near the defense team,” LaFollette says. This vantage point gave the reporter-advocate and his camera a clear view of Bryan’s face.

“The pictures from the Science Service archive shed light on how a hotly debated trial was literally hot—so hot it had to be held outdoors,” Lewenstein says. “We see how close everyone had to sit as they struggled with deep intellectual, religious, and political ideas.”

Scopes was convicted and fined, but the verdict was eventually overturned on a technicality. Shortly after the trial ended, Science News-Letter published an appeal for a scholarship fund so that Scopes could attend graduate school. Scopes chose to study geology at the University of Chicago and later worked in the oil industry.

Hidden treasures

The extensive correspondence and the many photos in the Science Service collection may provide important insights into the creation of a public image for science and scientists. “The records tell a historian how science news was constructed,” LaFollette says. “They also often reveal a great deal about the construction of science itself and the interactions between scientists.”

“In Science Service,” she adds, “we can now see that the organization, in its first 20 years, was much more crucial for the development of science popularization than historians had believed before.”

LaFollette is also writing a book about radio broadcasts popularizing science, including the Adventures in Science series produced by Science Service from 1935 until the 1950s.

Last summer, Smithsonian intern Mary Tressider, a student at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Mass., created an online exhibit highlighting the important, pioneering roles that women played as reporters for Science Service (http://siarchives.si.edu/research/sciservwomen.html).

Historian Sevan Terzian of the University of Florida in Gainesville is now delving into the Science Service archive to look at the organization’s role in science education, particularly after-school activities such as science clubs and fairs.

“The collection has proved to be exceptionally useful.” Terzian says. “I have … found radio-program transcripts, correspondence, brochures, pamphlets, and press releases by Science Service from the 1930s to the 1950s.”

“What else might come from the Science Service archives?” Lewenstein asks. “Who knows? That’s part of the fun of being a historian.”