Trans Fats

New studies add to these fats' image problem

- More than 2 years ago

Supermarkets are stocked with enough varieties of butter, margarine, and spreads to give a shopper pause. It’s no small task to decipher which sticks and tubs contain which types of fat—and which fats are best for your health.

The skinny on fat keeps changing. Whereas nutritionists first differentiated between just a couple types of fats, a subcategory of the forms that seemed less harmful later came to be seen as risky, after all (SN: 5/21/94, p. 325). Over the past several years, evidence has continued to mount against the food component called trans fat. It’s been implicated in diseases ranging from coronary heart disease to diabetes.

Trans fats are almost everywhere in the U.S. diet. They transform vegetable oils into solid substances suitable for use in many foods. From french fries and margarine to store-bought cookies and crackers, trans fats are ubiquitous in fast food restaurants and grocery stores. Consumers don’t yet see these fats listed in the “Nutrition Facts” box on a tub of margarine, but they already can find dairy-aisle spreads advertised as being low in trans fat.

Now, while some researchers are conducting new studies to further investigate the role of trans fats in disease, others are learning how to make appealing foods with fewer trans fats. To be sure, both the basic and applied sciences of trans fats have become hot.

Carbon chains

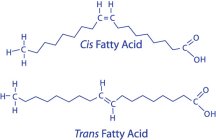

Categories of fats get their names from their patterns of hydrogen atoms in the molecules. All fatty acids, which make up fats, contain chains of carbon atoms with hydrogen atoms attached to some or all of the carbons.

Unsaturated fats, such as those in corn and soybean oil, have double bonds at a variety of positions along their carbon chains. Typically, each carbon atom participating in a double bond also bonds to one hydrogen atom and the next carbon atom in the chain. Fats with one double bond are called monounsaturated, and those with more double bonds are polyunsaturated.

Saturated fats, such as those found in butter, get their name because they don’t have any double bonds—the carbon chain holds the greatest possible number of hydrogen atoms. Earlier research linked saturated fats to a variety of diseases, so many people switched to products, like margarine, that contain unsaturated fats.

Trans fats contain a type of unsaturated fatty acid that didn’t raise much of a health alarm until the past decade. Their name refers to a feature of their bonds. At the location of each double bond, a fatty molecule bends, either in a so-called cis or trans direction. Cis configurations are those in which the molecule on both sides of the double bond bends in the same direction—both either up or down. In trans configurations, the

chain bends in opposite directions on either side of the double bond—making a zigzag.

There are some naturally occurring trans fats, primarily in the meat of cows and other ruminant animals. But most trans fats in foods come from the processing of oils for margarines, shortenings, and prepared foods.

To transform vegetable oils into solid or semi-solid substances, producers change some double bonds into single bonds. The most common process that they use is called partial hydrogenation. This method leaves many fatty acids in the trans formation, which assemble, like a stack of chaise lounges, into a solid much easier than those in the cis shape do.

Links to heart disease

As of yet, there isn’t a consensus among health professionals about how a diet high in trans fats compares to one heavy in other fats. However, the most recent research is adding to the already worrisome case against trans fats. The fats first raised concerns because studies in 1990 suggested that they raise concentrations of the so-called bad form of cholesterol, or LDL, in the body while lowering levels of HDL, the good form of cholesterol. What’s more, other research since then has linked diets containing a lot of trans fat to coronary heart disease.

The conclusions of two new reports by Dutch researchers strengthen the connection between coronary heart disease and high trans-fat intake. In the first study, reported in the March 10 Lancet, scientists collected detailed information on the dietary habits of 667 elderly men from Zutphen, the Netherlands, in 1985, 1990, and 1995. By the most recent survey, 98 of the men had developed or died from coronary heart disease.

The disease turned up more often in those men who had eaten more trans fats than the other volunteers ate, report Daan Kromhout of the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment in Bilthoven, the Netherlands, and his colleagues. Looking at each man’s 1985 diet, Kromhout and his colleagues found that for every additional 2 percent of trans fats consumed, a man was about 25 percent more likely to develop coronary heart disease within 10 years.

The Zutphen men in 1985 ate more trans fats than most people in western Europe and the United States did, the researchers point out. Over the study’s duration, the men surveyed decreased their trans-fat intake from an average of 4.3 percent of their diet in 1985 to 1.9 percent in 1995. Yet people in western Europe generally consume about 0.5 to 2.1 percent of their food as trans fats, and those in the U.S. take it in as about 2 percent of their food, the researchers say. The report’s conclusion should be confirmed in a much larger survey, notes Kromhout.

More evidence for a link between trans fatty acids and coronary heart disease appeared in a study in the July Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. In this small trial, Nicole M. de Roos of Wageningen University in the Netherlands and her colleagues provided diets that were high in either trans fats or saturated fats to 29 healthy men and women.

For 4 weeks, half the volunteers ate food prepared with margarine made from partially hydrogenated soybean oil, so their diets were rich in trans fats. The other half ate food prepared using palm kernel oil, so their diets were high in saturated fat. Then, the people on the trans diet switched to the saturated fat diet, and vice versa.

As expected, the researchers found that the trans-heavy diet reduced concentrations of good cholesterol in the blood. These HDL concentrations were 21 percent lower in participants when they were on the trans diets than when they were on the saturated fat diet, de Roos and her colleagues report.

Meanwhile, the researchers also found that blood vessel function, proposed to be an indicator of coronary heart disease, decreased in subjects while they were on the high-trans diet. The diet’s impact seemed to be reversible, says de Roos. When participants on the trans diet switched to the saturated fat diet, their blood vessel function improved.

Further studies are needed to confirm that blood vessel function indeed is indicative of heart disease, notes de Roos. Also, she adds, it’s not yet clear whether lowered concentrations of HDL in the blood of trans-diet subjects decreased blood vessel function or whether the result is a separate action of the fats.

In yet one more recent report, another correlation has pinned blame on trans fats. In this case, the disease is diabetes. Walter C. Willett of the Harvard School of Public Health and his colleagues followed 84,204 women for 14 years, asking them about their diets every few years.

The researchers found no correlation between the most common form of diabetes and the intake of total fat or of saturated or monounsaturated fatty acids. However, a woman’s risk of developing this adult onset, or type II, diabetes increased with greater intake of trans fats, report Willett’s team in the June American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

On the other hand, eating more polyunsaturated fats that haven’t been artificially hydrogenated, and so don’t contain elevated amounts of trans fats, lowered the risk of type II diabetes in the women.

“The more you look, the more problems you see with trans fats,” says Willett.

No consensus

With all of these negative possibilities for a diet high in trans fats, some researchers such as Kromhout and Willett say it already makes sense to cut back on them. Yet there isn’t consensus on which fats in the diet might replace them.

Rick Cristol of the Washington, D.C.-based National Association of Margarine Manufacturers, for example, points to a study published last year by researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. The work—funded by the university, the margarine association, and the United Soybean Board—found that a diet including margarine, even with its trans fat, reduces bad cholesterol on average more than does a diet including butter, which contains much saturated fat.

The work by de Roos came to the opposite conclusion. “I think we can be fairly certain that trans fats are worse than saturated fats,” she says. On the other hand, she adds, people shouldn’t avoid trans fats by eating more saturated fat.

There’s yet another complicating aspect of the debate. From its studies, Kromhout’s team concludes that there’s no difference in the behavior of manufactured trans fats, such as those made through vegetable oil processing, and those found in ruminant animals. They’re all bad, these researchers say.

However, Antti Aro of the National Public Health Institute in Helsinki finds this conclusion far from convincing. In fact, adds Aro, many trans fats from animals transform in cows or people to a specific type of trans fat known as conjugated linoleic acid, or CLA. Evidence is building that this fat has a variety of benefits, such as fighting cancer and enhancing immunity (SN: 3/3/01, p. 136: The Good Trans Fat).

Yet researchers point out that most trans fat, should someone wish to avoid it, is found in packaged and prepared foods. Although many people in the United States don’t eat as much trans fat as do the subjects in the recent studies, some do. It’s easy. Many consumers are unaware of just how much trans fat is in prepared foods such as store-bought cookies and crackers, says de Roos.

Some researchers, like David Kritchevsky of the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, state that trans fats tend to get more bad publicity than they deserve. Scientists need to pinpoint which trans fats are the problem, says Kritchevsky, who notes that most studies don’t identify the locations of trans double bonds in the fats consumed. Moreover, he says, other types of foods that are eaten by participants could influence the outcome of studies designed to measure only trans fats’ effects.

Kritchevsky, for one, says that people shouldn’t panic over trans fats. Some scientists would have “the public scared to death about anything with the word trans in it,” he says. Although people have been eating more and more hydrogenated oils full of trans fats in the last few decades, there’s been a simultaneous decrease in heart disease, he notes.

“I wouldn’t recommend that you run out and look for [trans fats],” Kritchevsky says, but he’d be interested in seeing more research determining how these substances behave in the body.

Manufacturers react

Despite the lack of a consensus on some matters, studies linking diets high in trans fats to ill health are leading some manufacturers and researchers to try to lower the trans fat content in food (see http://www.sciencenews.org/sn_arc97/5_31_97/food.htm).

Cristol says that margarine manufacturers have greatly reduced their products’ trans-fat content in recent years. They would welcome Food and Drug Administration labeling of trans fats, he adds, to show just how little is present in margarine as compared with many other foods.

Food producers, especially in Europe, have worked on various methods to lower the trans-fat content of foods in recent years. Some researchers dilute hydrogenated oil with liquid oil, while others avoid hydrogenation altogether.

Now, Gary R. List and his colleagues at the Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Peoria, Ill., have modified the century-old, workhorse technique of hydrogenation to produce a product firm enough to be used in margarine and shortening but that creates fewer trans fats than the ordinary method does.

During conventional hydrogenation, oil is heated under pressure in the presence of a chemical catalyst. When hydrogen is added, these atoms join the carbon chain and displace some or all of the double bonds between carbon atoms in the oil molecules.

In a laboratory-scale experiment, the USDA research team hydrogenated soybean oil using an unusual solvent, known as supercritical carbon dioxide. They also applied higher pressures and lower temperatures than are commonly used in the industrial process.

In the February Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, List and his colleagues reported that their method produced hydrogenated oils sufficiently solid for use in foods such as margarine but containing lower amounts of trans fats. The new hydrogenation products contain less than 10 percent trans fatty acids, compared with the 10 to 30 percent typically present in hydrogenated oil, says List.

If this technique works at making usable, solid hydrogenation products, the margarine association would be excited about it, says Cristol.

At the very least, the process adds a new twist to the still unfolding trans fat story.