- More than 2 years ago

With increasing frequency, today’s chemists are sending their students off in search of Victorian-era scientific reports. These obscure, 19th-century references to the work of organic chemistry’s earliest practitioners are now appearing among the endnotes of an exploding number of present-day journal articles.

The reason? Researchers have recently become focused on recapitulating a century’s worth of chemistry in an utterly new way. This time around, they hope to use a tantalizing new repertoire of solvents, known as ionic liquids, that can get the job done without the stink, mess, pollution, and toxicity of the workhorse solvents that have characterized much of organic chemistry so far.

This research looks forward, as well as backward. The odd new liquids, which ultimately could be made in countless variations, are not just new solvents for old reactions. They’re also leading to new chemical processes, tools for environmental cleanup, and novel materials.

And there’s another promising aspect to these environmentally friendly liquids: Industry seems quite excited about them. “People have started to see the glimmer of what kinds of opportunities they offer,” says Robert Morland, a chemist at the North American office of British Petroleum in Naperville, Ill. “If you look at just the number of papers and patents in ionic liquids and plot that versus years, it’s gone up exponentially.”

Ionic solutions

So, what are these materials that could blend environmental gentleness with industrial innovation? Water and organic solvents, such as toluene or dichloromethane, the stuff of household paint remover, are made of molecules. Ionic liquids, by comparison, are made of positively and negatively charged ions–much the way table salt, sodium chloride, contains crystals made of positive sodium ions and negative chlorine ions, not molecules.

While table salt doesn’t melt below 800C, ionic liquids remain fluid at room temperature. In fact, ionic liquids generally are liquid from about –100C to 200C.

Theoretically, a trillion ionic liquids are possible, says Kenneth R. Seddon, a chemist at the Queen’s University of Belfast, Northern Ireland who runs an ionic liquid research center there known as QUILL, an acronym for Queen’s University Ionic Liquid Laboratory.

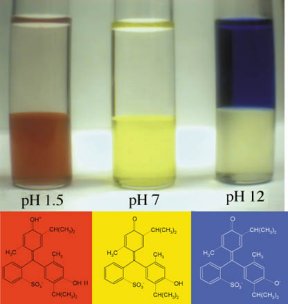

To make an ionic liquid, researchers can select from dozens of small, negatively charged ions, or anions, such as hexafluorophosphate ([PF6]–) and tetrafluoroborate ([BF4]–), and hundreds of thousands of larger, positively charged ions, or cations, such as 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium or 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium, says Seddon. Ionic liquids are thus “designer solvents,” he says. Chemists are free to pick and choose among the ions to make a liquid that suits a particular need, such as dissolving certain chemicals in a reaction or extracting specific molecules from a solution. Seddon’s lab has about 130 of the liquids on its shelves already.

Researchers studying ionic liquids believe that they remain liquid at room temperature because their ions don’t pack well. Combining bulky, asymmetrical cations with smaller, evenly shaped anions is “like gluing an octopus to a basketball,” says Morland. This leaves the ions disorganized, without a regular structure–in other words, liquid.

In contrast, the sodium and chlorine ions in table salt are like oranges in a crate. They pack closely into solid, crystalline structures because they have similar sizes and shapes, says Morland.

Unlike typical organic solvents, ionic liquids tend not to give off vapors, so researchers say they’re less hazardous and more convenient in the laboratory, and they’re less likely to pose air pollution problems. What’s more, chemists have found that they can extract products and recover chemical catalysts from ionic liquids easily and then recycle the liquid to use over and over.

Reactions that occur in organic solvents have been the standard way to make countless products. Now, many of these time-tested reactions have been repeated anew in ionic liquids, says Seddon. The list of successful reactions completed in the new liquids rings familiar to any college organic chemistry student: hydrogenation, nitration, halogenation, Diels-Alder, Friedel-Crafts, and on and on. These are the fundamental reactions by which raw chemical ingredients become medicines, plastics, cosmetics, fuels, and thousands of other materials.

As viscous as water–or a little more so–ionic liquids are easy to work with, says James H. Davis Jr., a chemist at the University of South Alabama in Mobile.

“Anybody anywhere can make them and handle them,” says Davis. A chemist can basically take any organic reaction out of a textbook and try it in an ionic liquid.

A hot topic

Ionic liquids may be a hot topic for chemists now, but when they were first studied they were literally hotter.

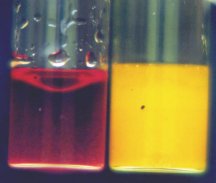

The earliest ionic liquids in the literature were probably created unintentionally in the late 19th century, says John S. Wilkes, a chemist at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo. He’s found references to a red oil, probably an ionic liquid, that appeared during certain reactions.

Later, during the 1940s, aluminum chloride-based molten salts were used for electroplating, usually at temperatures of hundreds of degrees Celsius.

In the early 1970s, Wilkes and his colleagues began much of the work behind today’s ionic liquids revival. They had been trying to develop better batteries for missiles, nuclear warheads, and space probes. The team’s batteries required molten salts to operate, but such substances were hot enough to damage nearby materials. So, the chemists looked for salts that remain liquid at lower and lower temperatures. Eventually, they identified one that’s liquid at room temperature.

The work plodded on into the early 1980s, as Wilkes and his colleagues continued to improve their ionic liquids for use as battery electrolytes (SN: 4/24/82, p. 282). Then, Seddon traveled to the Air Force lab for a visit.

It struck Seddon that there were broader opportunities for these materials, particularly as solvents for organic reactions. He and a small community of researchers began making ionic liquids, testing their properties, and trying out old reactions in them. Results from this work eventually encouraged Seddon to found QUILL in 1999.

After talks with Seddon, Robin D. Rogers, an ionic-liquid chemist at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, helped establish in 1998 the Center for Green Manufacturing, which has become another stronghold in the fledgling field. Green refers to processes that are effective but sidestep the environmental drawbacks of much traditional industrial chemistry.

Although interest in ionic liquids picked up in the late 1990s, Seddon and Rogers still had trouble rounding up 50 or so chemists to attend an April 2000 workshop in Crete on the topic.

Recently, however, interest in ionic liquids has skyrocketed. For example, Rogers reports that at the American Chemical Society meeting in San Diego last April, more than 275 people jammed into the meeting room on the first day of a 5-day symposium in which more than 80 chemists gave oral presentations on ionic liquids.

Ten years ago, chemists published about 10 papers a year on ionic liquids, adds Seddon. Today, it’s about 10 papers a week.

And that doesn’t represent the unreported work going on at corporate labs, adds Al Robertson, a chemist at Cytec in Niagra Falls, Ontario. “It’s not just a passing interest anymore,” says Robertson, whose company has developed a family of phosphonium-based ionic liquids.

A hard sell

Ionic liquids might make chemical processes cleaner, but unless the liquids can improve a company’s bottom line, they would be a hard sell to management and many stockholders.

In fact, there are plenty of commercial incentives for industry to embrace such research, according to Morland of BP. One of them is that compounds dissolve in ionic liquids in ways that enable chemists to separate products easily later, he says. Another is that ionic liquids can host a variety of catalysts in more convenient, effective, and recyclable ways than can conventional organic solvents.

Moreover, some reactions occur at a faster rate or yield a more valuable proportion of products and by-products when done in an ionic liquid, says Morland.

The expectation that ionic solvents will be environmentally benign also has “a significant positive impact,” Morland adds. If BP could use ionic liquids in its processes, it could decrease use of polluting volatile organic solvents, he says. Furthermore, ionic liquids could make reactions more efficient, thus reducing waste.

Jimmy W. Mays, a chemist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, has learned just how interested industry has become. “I gave a talk at the [American Chemical Society] meeting in San Diego back in April, and I was mobbed after the talk,” says Mays, who uses ionic liquids to make polymers. “I’ve had calls from people at companies saying, ‘Look, we want to give you money to work on this.'”

More than just green

Recently, researchers such as Mays have discovered that ionic liquids are more than just green versions of organic solvents. They’ve been shown to support delicate enzyme-catalyzed reactions, to make new materials, and to conduct heat efficiently.

Wilkes has moved beyond batteries to discover that an ionic liquid will dissolve the black rubber of discarded tires, which is hard to do with organic solvents. The polymers in the ionic liquid can then be recovered for recycling, he says.

Other researchers have found still more applications for ionic liquids.

Consider Mays. He got caught up in the research 2 years ago after he obtained some ionic liquids from Rogers. He immediately found that he could use them to make commercially important polymers, such as the ones in Styrofoam and Plexiglas, 10 times faster than with traditional solvents.

Moreover, the resulting polymers had extraordinarily high molecular weights, which leads to high-quality materials.

Since then, Mays has used ionic liquids to make block copolymers–compounds that have a long stretch of one polymer attached to a long stretch of another–including ones that can’t be made in any other way. He can even make so-called statistical copolymers, which have particular patterns of individual units in the polymer chain.

The University of South Alabama’s Davis also stumbled into ionic-liquid chemistry. He was working with imidazolium salts when he read that the salts are commonly used in ionic liquids. He started out trying to perform one traditional organic reaction in an imidazolium ionic liquid, and he succeeded.

Now, Davis makes task-specific ionic liquids–substances that act as both solvent and catalyst for specific chemical jobs. He attaches an ionic liquid’s bulky cations to groups of atoms that tend to bind to particular metal contaminants, such as mercury or cadmium.

“Literally, the arms on the cations reach up and grab the mercury and cadmium [from the water] and pull them into the ionic liquid,” says Davis.

He’s also altered cations to grab uranium and americium, which are two waste materials from nuclear weapons production. “This is potentially quite significant,” says Davis, “because there are literally millions of gallons of contaminated water stored at places like the Hanford nuclear site” in Washington State.

Now, Davis has even developed ionic liquids that will pull carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide out of a gas. Natural gas often contains these impurities when it’s discovered in the ground. Since it doesn’t burn, carbon dioxide lowers the fuel value of natural gas. Although hydrogen sulfide burns, it generates sulfur oxides that contribute to acid rain.

An ionic liquid could potentially even pull carbon dioxide, the most important of greenhouse gases, from factory exhaust. It might also yank carbon dioxide out of the confined air of the space shuttle or International Space Station, says Davis.

A happy compromise

With all their possible environmental and industry benefits, ionic liquids seem to offer a happy compromise. But hurdles remain before they can become major components of the chemical industry.

For one, the price of the liquids needs to fall. Organic solvents cost just a few cents per liter, while the new ionic liquids can cost hundreds of dollars for the same amount. However, ionic liquids may be recyclable, so the cost could be a capital expenditure, like buying a piece of lab equipment, says Mays.

And as more people use ionic liquids, some researchers argue, the price should go down.

Another obstacle is the current dearth of toxicologic data on these substances, says Rogers. Many researchers believe that ionic liquids pose little or no health danger, but studies must be completed before any of them can be proved safe and sold or used commercially.

And then there’s the case of patents. Can someone claim the patent on a whole family of ionic liquids? Who owns the right to a company’s valuable chemical reaction if the patent only lists organic solvents and not unforeseen ionic liquid solvents? Such problems will have to be worked out.

Finally, laboratory-scale experiments will need to be scaled up for factory-size processing–a trick that often quashes the promise of laboratory successes. A couple of pilot trials have taken place, but no one has yet taken the leap to full-scale commercial production using ionic liquids.

“If you look at the total cost of making [an ionic liquid]–raw materials, environmental impact, use . . . and getting rid of it–is it really better than an organic solvent?” asks Rogers. “These questions are still to be answered.”

So, when might ionic liquids move into the mainstream? Cytec, for one, is waiting to see which ionic liquids generate a demand, says Robertson. If there is a market, he adds, the company would be able to produce at least one of its own ionic liquids by the truckload.

Meanwhile, Seddon speculates that chemistry textbooks will add ionic liquids in the next year or two. Then, new crops of chemists will enter their professional lives with ionic liquids on their minds. Within a decade, Seddon expects, every academic and industrial chemist will have a jar of ionic liquid within reach, and some chemical companies will use tanks of it.