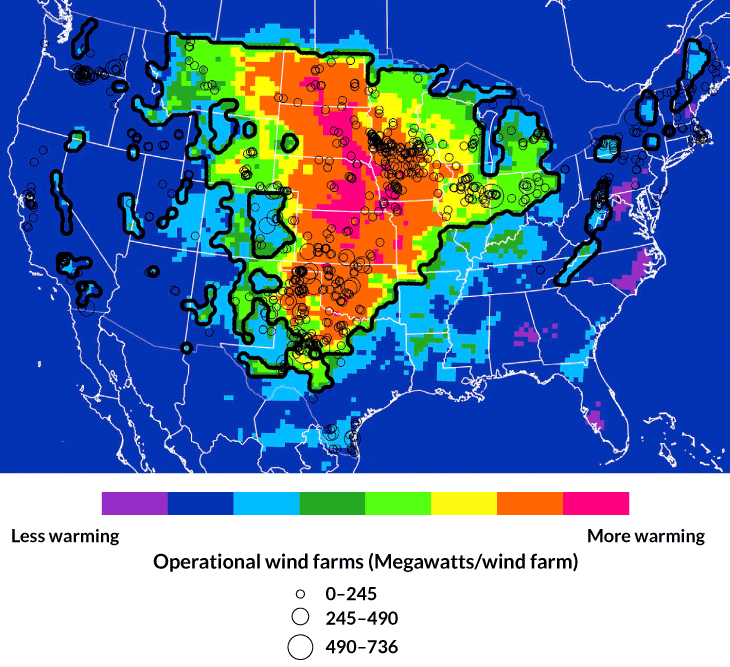

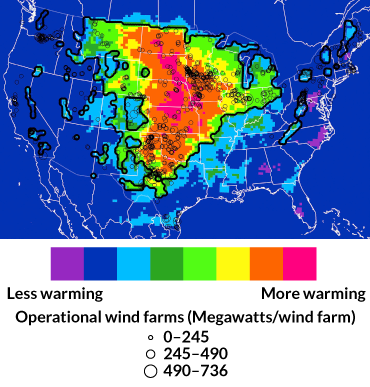

How wind power could contribute to a warming climate

Enough turbines to generate all of America’s power would warm the U.S. by 0.24 degrees Celsius

WINDY WORLD In a United States dotted with enough wind turbines (such as these at Adams Wind Farm in Minnesota) to generate all of its power, the country would get a bit hotter.

William De Hoogh/Unsplash.com