Debate grows over whether X-rays are a sign of dark matter

Failure to spot telltale glow from nearby dwarf galaxy sets back search for dark matter

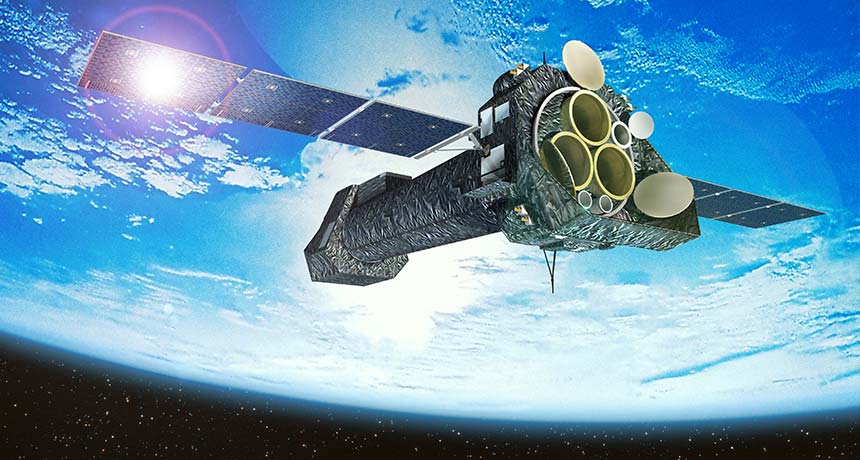

NOTHING TO SEE HERE The European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton space telescope, illustrated here, didn’t find a possible signature of dark matter coming from the dwarf galaxy Draco.

D. Ducros/ESA

The search for a suspected calling card of the universe’s most elusive matter has come up empty.

Multiple days of telescope time spent looking for a specific X-ray glow coming out of the nearby dwarf galaxy Draco failed to turn up any signal, two University of California, Santa Cruz astrophysicists report online December 7 at arXiv.org. Finding such a glow would have offered a compelling clue for the identity of dark matter, the invisible, inert stuff that makes up more than 80 percent of the universe’s matter. The study’s authors say that the absence of the X-rays in Draco, one of the most dark matter–dominated objects known, means that scientists had previously detected the X-ray emissions of interstellar atoms rather than dark matter.

Not everyone agrees with the study’s conclusion, including a different team of scientists who commissioned the lengthy Draco observations and are reviewing the same data. Those scientists, who haven’t yet published their analysis, say they can’t rule out the possibility that dark matter produces the X-rays that have been spotted emanating from other cosmic objects.

Scientists know dark matter permeates the cosmos because, among other evidence, the outer regions of galaxies spin faster than they should based on the distribution of the galaxies’ stars and gas. In an attempt to identify the particles that make up dark matter, some scientists analyze images of dark matter–rich regions like galaxy clusters and dwarf galaxies in search of gamma rays, X-rays or other unexpected signals. Their hope is that dark matter particles emit observable radiation when they decay or collide with each other (SN Online: 11/4/14).

Scientists flagged one promising signal in February 2014: bursts of X-rays with an energy of about 3,500 electron volts that consistently appeared in a set of 73 galaxy clusters. Other groups soon found X-rays streaming from the Perseus galaxy cluster, Andromeda and the center of the Milky Way, too.

Theorists quickly pointed out that dark matter in the form of a proposed particle called a sterile neutrino could decay and emit radiation at that energy. “It was very exciting,” says Stefano Profumo, an author of the new paper. “We had a signal that matched with a predicted dark matter candidate.”

But dark matter isn’t the only way to explain the X-rays. Profumo and others argued that initial studies underestimated the role of a kind of decidedly undark matter — potassium atoms — that can also emit 3,500-eV X-rays in galactic gas clouds. To settle the issue, a team led by Alexey Boyarsky, a particle physicist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, pointed the XMM-Newton space telescope at Draco. The dwarf galaxy, located about 270,000 light-years away, contains lots of dark matter but barely any potassium-carrying gas.

For the new study, Profumo and colleague Tesla Jeltema, who are not part of Boyarsky’s team, analyzed the publicly available XMM-Newton data along with a previous Draco observation. They found no evidence that the galaxy radiates 3,500-eV X-rays. Profumo says their results prove that the X-rays in the other galaxy clusters could not have come from the decay of dark matter.

Boyarsky agrees that there is no strong X-ray signal coming from Draco. But he says he’s not convinced that the data rule out that dark matter decays into X-rays. He expects to share a more careful analysis encompassing more telescope data within the next few weeks.

Esra Bulbul, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who is working with Boyarsky, says the new data hurt the case for sterile neutrinos composing dark matter. But she says that other kinds of dark matter particles could produce a feebler emission of X-rays that might explain the Draco observations. “Draco is a good clue, but I’m afraid it’s not going to be conclusive enough to evaluate the dark matter origin,” she says. “We have seen the signal in so many clusters.”

Bulbul expects to narrow down the list of potential X-ray emitters next year after the launch of ASTRO-H. That space telescope will be able to separate the contribution of potassium atoms from the rest of the X-ray signal, she says.